If you’ve been reading this blog regularly, you already know the basics about peak oil:

- It’s not a kooky conspiracy theory. The obsessively mainstream International Energy Agency, which refused to even acknowledge the possibility of peak oil for years, officially admitted it was real three years ago. Not only that, they even put a date on peak production of conventional oil: 2006. In other words, it’s already happened.

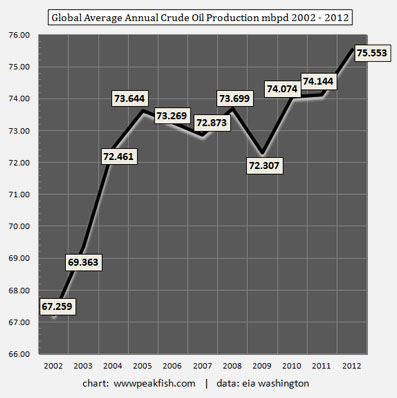

- The peak in conventional oil will be offset by new “unconventional” production: shale oil, tar sands, deepwater oil, and so forth. But that oil is both expensive and in limited supply. Shale oil has gotten immense publicity, but it’s unlikely to ever get much above a production rate of 1 million barrels per day. That’s 1 million out of a current global production of about 85 million (75 million barrels of crude oil and about 10 million barrels of petroleum liquids).

- Other unconventional sources will add more to this, but unless there’s some huge discovery of unconventional oil that we know nothing about, it’s likely that we’re already at or close to peak oil right now. New production of unconventional

oil is only barely replacing declines in older, more mature fields, and decline rates in older fields are only going to get worse in the future.

oil is only barely replacing declines in older, more mature fields, and decline rates in older fields are only going to get worse in the future.

Over at Wonkblog, Brad Plumer interviews energy analyst Chris Nelder about peak oil, and Nelder has this to say about unconventional oil:

BP: So what we’re seeing is that the world can no longer increase its production of “easy” oil — many of those older fields are stagnant or declining. Instead, we’re spending a lot of money to eke out additional production from hard, expensive sources like Alberta’s tar sands or tight oil in North Dakota.

CN: Right, and that’s entirely consistent with peak oil predictions, which said that extraction would plateau, that the decline in conventional oil fields would have to be made up by expensive unconventional oil. Right now, we’re struggling to keep up with declines in mature oil fields — and that pace of decline is accelerating.

Mature OPEC fields are now declining at 5 to 6 percent per year, and non-OPEC fields are declining at 8 to 9 percent per year. Unconventional oil can’t compensate for that decline rate for very long.

Even all the growth in U.S. tight oil from fracking, which has produced about 1 million barrels per day, hasn’t been enough to overcome declines elsewhere outside of OPEC. Non-OPEC oil has been on a bumpy plateau since 2004.

There’s more oil out there. But it’s hard to find; expensive to extract; declines quickly; and is usually disappointing in volume (Nelder: “Anticipated production growth for tar sands has consistently failed to meet expectations, year after year after year. Ten years ago, tar sands production today was expected to be twice what it actually is.”). We may or may not be quite at peak oil yet, but we’re either there already or else very, very close. And either way, production costs of unconventional oil make it unlikely that oil will ever get much below $100 per barrel again. This makes it a significant restraint on global economic growth, and unless and until we make a huge switch to renewable energy, this will continue permanently. Any time you see a medium or long-term forecast of global growth that doesn’t mention oil constraints, you should probably take it with a big grain of salt.