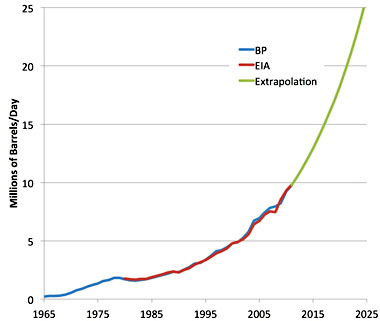

Stuart Staniford extrapolates China’s demand for oil and comes up with the chart on the right. His conclusion:

Stuart Staniford extrapolates China’s demand for oil and comes up with the chart on the right. His conclusion:

That’s another 15mbd in the next thirteen years or so. Just for China. If you compare this to things like the extra 4mbd you might hope for from tar sands in this time frame, or the 2mbd that global crude supply has increased since 2005, you can see that this is going to stress the global oil system a lot. Either the global crude supply is going to grow a lot faster than it has been, or OECD oil consumers are going to have to consume a great deal less than they are now, or China (and other rapidly growing consumers) are going to have to slow down a lot.

Whichever is the case, it’s hard to see how any combination of the above happens on the necessary scale without prices a lot higher than the $100-$120 we’ve been paying in the last few years. The comparative truce in the oil markets during 2009-2013 seems like it cannot last forever.

Shale oil and tar sands are simply nowhere near big enough to keep up with this. From a climate change perspective, that’s a good thing. From a global economic perspective, it’s not so good. It means that demand for oil is now permanently pushing up against supply, and will be moderated in the future primarily by oil price spikes produced when economic expansions drive oil demand above supply constraints, thus producing global recessions. But you already knew that, right?

POSTSCRIPT: The more optimistic take on this is that sometime soon everyone will figure out that we’ve reached a point of oil-constrained growth, and this will drive huge new investment in renewable energy. The question is how long this will take. Permanently higher prices would certainly do the trick, but booms and busts have a different effect on investment and on confidence in future growth. So it might take a while.