Michael D’Antonio and John Gerzema take to the LA Times today to propose yet another origin story for the term “Black Friday”:

Michael D’Antonio and John Gerzema take to the LA Times today to propose yet another origin story for the term “Black Friday”:

The day was originally nicknamed Black Friday by police officers who dreaded the traffic jams, bumper thumping and misdemeanors that arise when so many people converge on shopping districts and malls.

Eventually the term came to describe the start of the period when retailers see profits for the year and a kind of retail gluttony so divorced from the true spirit of the season that it made all but the most benumbed consumers feel conflicted, if not ashamed, of the excess.

Really? Police officers? I’ve never heard that one before. Here’s what I wrote back in 2005 after a search of the Nexis news database:

The first reference I found to the term “Black Friday” was in a World News Tonight segment by Dan Cordtz from November 26, 1982: “Some merchants label the day after Thanksgiving Black Friday because business today can mean the difference betweeen red ink and black on the ledgers.”

The news media then went into silence on the subject until a Washington Post story dated November 20, 1987, which provided the following advice: “Do not shop next weekend (unless you’re into S&M or S&Ls). The day after Thanksgiving is traditionally the busiest shopping day of the year — store workers call it ‘Black Friday.'”

This suggests that the phrase was invented by retail workers peering apprehensively out their windows at the post-holiday mobs waiting to shop. However, a story in the Post eight days later confirms that it is “the day when the surge of holiday buying — and profit — is supposed to put [retailers] into the black.” But this same story also includes the following explanation: “‘We call it Black Friday because it’s the busiest shopping day of the year,’ said Andria Tedesco, 19, who was waiting on customers at Bailey Banks & Biddle jewelry store.”

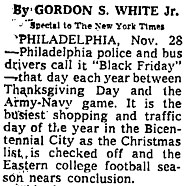

But what about this police officer thing? I no longer have access to Nexis, but a ProQuest search of the New York Times brings up a story about the Army-Navy game in 1975. The gist of the story is that crowds used to  flow into Philly on the Friday after Thanksgiving to shop, watch the game on Saturday, and then go home. But with the decline of the Army-Navy game, crowds were down.

flow into Philly on the Friday after Thanksgiving to shop, watch the game on Saturday, and then go home. But with the decline of the Army-Navy game, crowds were down.

The gridiron woes of Army and Navy aside, though, it seems unlikely that this was really a Philly-specific thing. So maybe it really was police officers who invented Black Friday. I have to admit that this makes more sense than the whole “day that retailers go into the black” theory, since Black ___day has, in other contexts, always signified something terrible, like a stock market crash or the start of the Blitz. So unless someone comes up with definitive evidence to the contrary, I think I’m going with the whole police/crowds story, with the retail profit theory tacked on at a later date by some overcaffeinated PR person trying to put some lipstick on a pig that had gotten a little too embarrassing for America’s shopkeepers.

UPDATE: In comments, Eric Baumgartner points to a thread at the American Dialect Society that, surprisingly, confirms the Philadelphia origin of the term. From a 1985 story in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

[Irwin] Greenberg, a 30-year veteran of the retail trade, says it is a Philadelphia expression. “It surely can’t be a merchant’s expression,” he said. A spot check of retailers from across the country suggests that Greenberg might be on to something.

“I’ve never heard it before,” laughed Carol Sanger, a spokeswoman for Federated Department Stores in Cincinnati….”I have no idea what it means,” said Bill Dombrowski, director of media relations for Carter Hawley Hale Stores Inc. in Los Angeles….From the National Retail Merchants Association, the industry’s trade association in New York, came this terse statement: “Black Friday is not an accepted term in the retail industry….”

….Retailers, in general, loathe the term. The Center City Association of Proprietors [Philadelphia], in fact, has been lobbying quietly for years to banish the word from the city’s vocabulary.

But the term goes back to at least 1966 — in Philadelphia, at least. An advertisement that year in The American Philatelist from a stamp shop in Philadelphia starts out: “‘Black Friday’ is the name which the Philadelphia Police Department has given to the Friday following Thanksgiving Day. It is not a term of endearment to them. ‘Black Friday’ officially opens the Christmas shopping season in center city, and it usually brings massive traffic jams and over-crowded sidewalks as the downtown stores are mobbed from opening to closing.”

So: apparently it did originate in Philadelphia, it did originally refer to big crowds and traffic jams, and retailers did hate the term and presumably created their own, more consumer-friendly origin story sometime in the 1980s. So there you go.