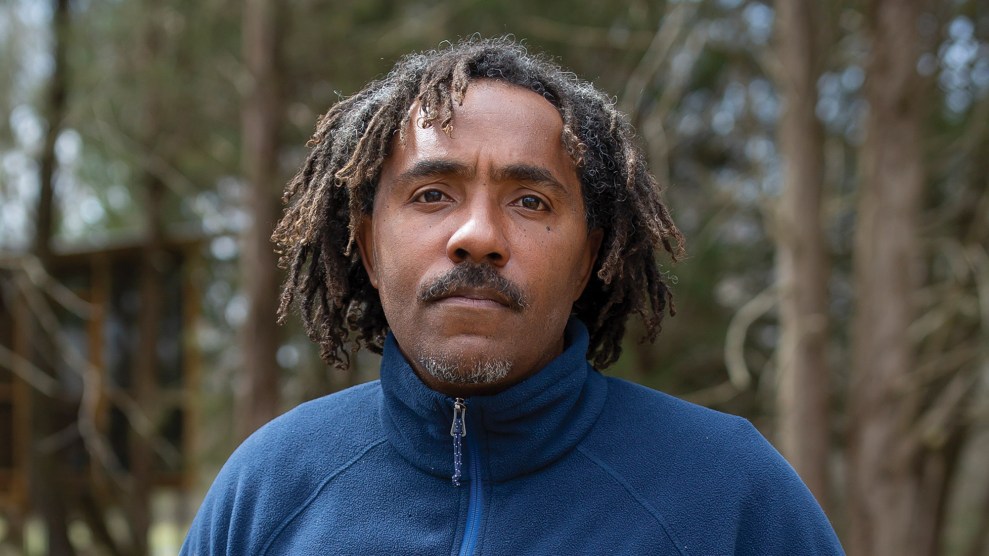

Cornelius Key, the son and grandson of sharecroppers, does something that was denied to his ancestors: He farms land that he owns. On 400 acres in Baker County, Georgia, he raises peanuts, corn, and cattle. Growing up, Key, 64, remembers that his father would often work the entire year on ground parceled out by the landlord in exchange for a share of the harvest—only to eke out no net income after a season of hard work. “Then you have to borrow money from [the owners] to have something for your family to eat, even during Christmas,” he says. Sharecropping involved a perpetual treadmill of debt, with sparse opportunities to get ahead.

To get a foothold in the area where he was raised—without the benefit of inherited wealth—Key had to turn to a different kind of debt: bank loans, the resource that has been the lifeblood of US farming for a century. The US Department of Agriculture plays a central role in agricultural debt markets, guaranteeing loans and acting as the lender of last resort—and it has used that power in a way that effectively transferred millions of acres of land owned by Black farmers into the hands of white ones. A 2019 US Government Accountability Office report found that minority and women farmers “get a disproportionately small share” of USDA loans; and a July 2021 analysis by Politico reporter Ximena Bustillo showed that in 2020, the USDA approved 71 percent of loan applications from white farmers, versus only 37 percent from Black farmers.

For the Black farmers like Key who survived this great dispossession, debt remains a major burden, one that falls much harder on them than on their white counterparts. Key employs an automotive metaphor to describe what it feels like to owe the USDA’s financial arm, the Farm Services Agency, more than $200,000: “When you have a worn-out truck, you’re scared to get on the road to take a long trip, because you don’t know what might happen—it might cut off; it might make it or it might not.”

This uncertainty, in many ways, just felt like a reality Key would have to live with. Then in March 2021, after years of pressure from groups like the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, a Georgia-based nonprofit association of Black farmers where Key works as a state coordinator, Congress took a small step toward redressing the USDA’s long history of racism and making it easier for people like Key to squeeze out a livelihood in agriculture: The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act allotted $4 billion to erase the debt for thousands of farmers of color with outstanding USDA-backed loans. Key’s FSA loan balance would have evaporated.

When Key and some of his Georgia peers first heard about the provision in March, they were still mapping out plans for the growing season. Assuming that the relief would come “pretty quickly,” he says, “we started putting more into this year’s crop than we normally do and started paying off other bills.”

But just as Biden’s USDA prepared to dole out the cash, a growing backlash threatened the program. Right-wing political operatives, including white nationalism enthusiast Stephen Miller, former President Donald Trump’s immigration whisperer, launched a swarm of lawsuits against the American Rescue Plan Act’s debt relief plank. According to the complaint from Miller’s group, the program represented unconstitutional “discriminatory racial preferences.” (The complaint did not mention that under Miller’s former boss, an unprecedented gusher of USDA subsidies flowed to white farmers, largely bypassing their Black counterparts.)

Their effort has succeeded so far: In June, after federal judges issued several injunctions, including one responding to Miller’s suit, the program was frozen before a single farmer saw a penny of debt relief.

It’s not exactly surprising that in a political era marked by hysteria over critical race theory and resurgent white resentment, compensating certain racial groups to try and counteract the centuries of systemic injustice they’ve endured would encounter a backlash. What experts often refer to as “race-conscious policies”—such as affirmative action in hiring and college admissions—often face stark opposition, typically driven by many deep-pocketed people who have benefited from these injustices and prefer to keep the status quo. In this case, this means white farmers and their allies.

Before President Joe Biden even had a chance to sign the American Rescue Plan Act on March 11, right-wing politicians and their media backers began to freak out about its debt relief provision. “What happened to equal protection under the law?” Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.) groused on Facebook on March 4. “This is wrong and un-American. I’m sure there are a lot of Americans out there that would love to have our tax dollars pay off all their debts. This is targeted to a very select few.”

A Fox News article published the day Biden signed the bill into law highlighted the complaints of Tennessee farmer Kelly Griggs, who is white: “Just because you’re a certain color you don’t have to pay back money? I don’t care if you’re purple, black, yellow, white, gray, if you borrow money you have to pay it back.” She also lamented the hit to taxpayers such as herself: “I’m going to have to pay for that.”

A few days later, Griggs’ grievances made the airwaves, anchoring a segment on Sean Hannity’s Fox News TV show. Standing in front of a massive combine, she presented herself as part of a group of “forgotten” farmers who had been excluded from federal aid. The US banking system doesn’t allow racism, she argued—even though racial bias in bank lending remains a well-documented phenomenon, including in agriculture. “If you go into a bank, if you go into any place that loans you money, they are not going to look at who you are by color or race, they are going to look at your numbers on a piece of paper and if you don’t meet that criteria and you don’t meet that rule, you don’t get that money, you don’t get that loan,” she insisted. Her husband, Matt Griggs, joined in, expressing concern that the bill might generate interracial tension: “I think this bill could not only divide—promote division in the farming community, [but also] just in people in general.” Not to be outdone, Fox News host Tucker Carlson ran his own outraged segment in May, featuring a white farmer denouncing the relief measure as “racism.”

Such lamentations are deeply ironic. A majority of these loans have always gone and are still going to white farmers. These disparities are reflected in another one of agriculture’s funding mechanisms: subsidies, which, unlike loans, are essentially gifts that don’t need to be paid back. Over the past century, as the number of Black farmers fell steadily (largely triggered by the USDA’s own actions), US farm policy has maintained a steady gusher of agricultural subsidies that flows almost exclusively to white people.

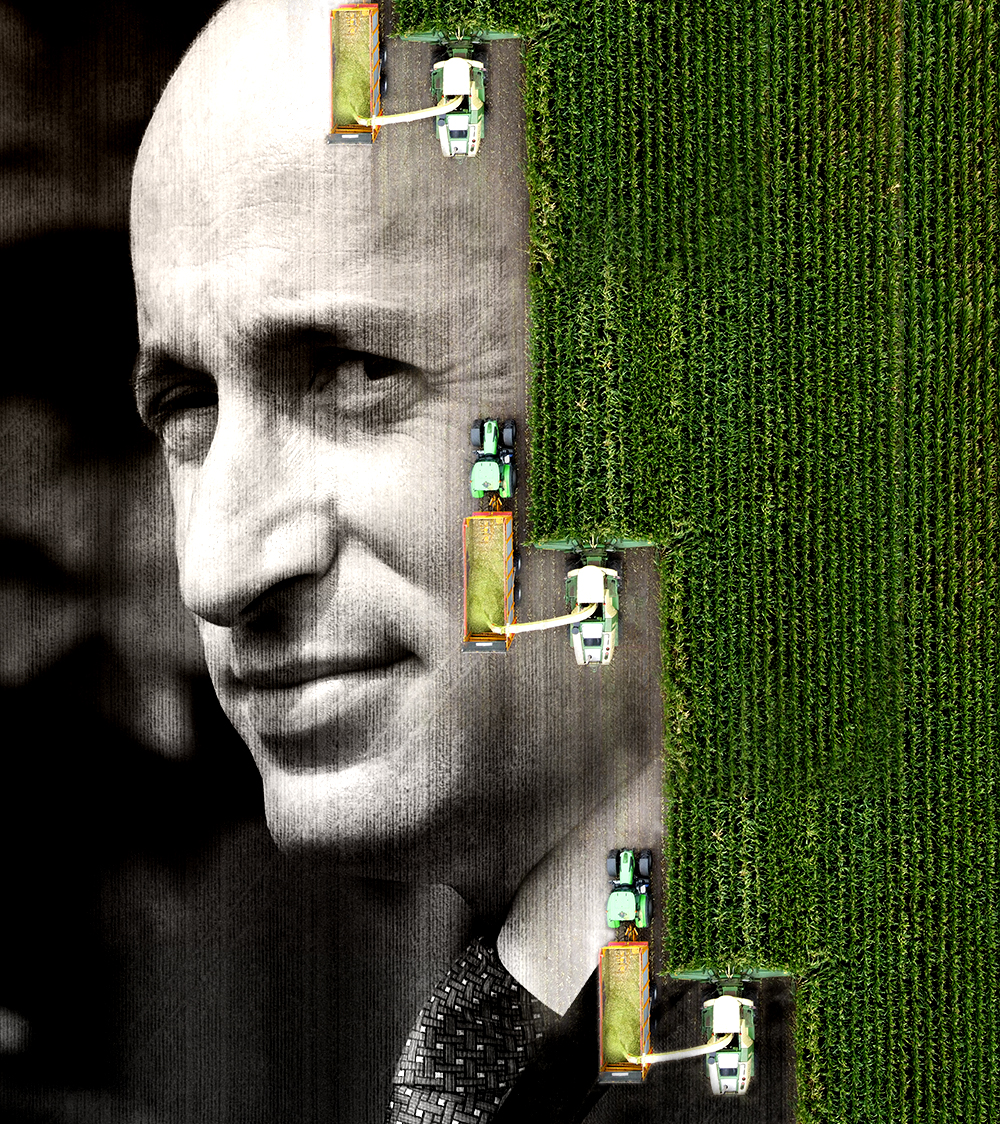

The trend accelerated under President Trump. Agricultural subsidies reached an all-time annual record of $46 billion in 2020, after hovering between $10 billion and $13 billion during pre-Trump years. The extra payments originated mainly from two sources: a program Trump initiated in 2018, without congressional input, seeking to shield “our Great Patriot Farmers” from the fallout of his trade war with China; and from congressionally mandated COVID-relief laws passed in 2020. The two sources had one thing in common: Around 99 percent of each went to white farmers.

Many of the loudest critics of the debt relief have benefited immensely from the system as is. For instance, Rep. Graves—the white congressman who denounced supporting farmers of color as “wrong and un-American”—represents a district in Missouri that received nearly $5 billion in farm subsidies between 1995 and 2020. His own family farm took in $661,153 over that same period, including $57,089 in 2019 alone. From his perch in the US House, Graves vigorously supports the subsidy system. Matt and Kelly Griggs—the ones fretting to Fox News about fairness and divisiveness—have had similar success with federal payments. Their operation took in $693,653 from 1995 through 2020, nearly half of it since 2017. (The Griggs have not responded to requests for comment on whether they still oppose debt relief for farmers of color.)

The debt relief program’s detractors didn’t stop their work with a few media hits. Several powerful Republicans quickly capitalized on their message and took the grievances to court. They were soon aided by several arch-conservative legal groups not even associated with agriculture, but who share their mission of opposing and undoing any attempts to tackle racial inequity and level the playing field.

Stephen Miller, a DC denizen raised in Santa Monica, hadn’t devoted much time to agriculture before launching a lawsuit to stymie the farmer debt relief program. The Trump confidante is best known for actively promoting white-nationalist ideals and shaping the administration’s intentionally cruel family-separation policy at the border. The farm-focused lawsuits are part of his latest venture.

In April 2021, presumably still stung by his boss’ ouster from the White House, Miller launched America First Legal, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit devoted to preventing “the radical left” from “opening America’s borders, shutting down American energy, trying to take over American elections, and violating the fundamental civil rights of the American People.” The group declared its intention to build a “team of some of the nation’s best legal, political, and strategic thinkers to challenge this lawlessness at every turn,” using “every legal tool at our disposal to defend our citizens from unconstitutional executive overreach.” The group’s overarching goal is to serve as a right-wing answer to the American Civil Liberties Union, using the courts as a means to advance a conservative agenda, Miller told the Wall Street Journal. Two other Trump administration stalwarts join Miller on AFL’s board: former Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and former Acting Attorney General Matthew Whittaker.

The group’s funding sources remain murky. Miller “declined to disclose his initial budget or fundraising so far, saying only that he had raised ‘a tidy sum of money’ which would pay for initial staff and finance an early round of cases,” the Wall Street Journal reported in April. The paper added that the funds have come from donors “who can write very large checks,” according to Miller, “but the group plans to begin soliciting small and medium-size donations soon.” The Internal Revenue Service had granted AFL 501(c)(3) nonprofit status on Sept. 30, meaning contributions to the group are tax-deductible and contributions over $5,000 in a single year have to be disclosed on publicly available IRS forms. (AFL won’t have to file its first one until 2022.)

One of AFL’s first acts, on April 26, was to sue USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack, demanding a halt to the debt relief program for farmers of color embedded in the American Rescue Plan. The complaint hinged on the claim that providing debt relief for farmers of color “lurches America dangerously backward, reversing the clock on American progress, and violating our most sacred and revered principles by actively and invidiously discriminating against American citizens solely based on their race.”

As plaintiff, AFL tapped Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller (unrelated to Stephen). In a bizarre turn of events, Sid Miller claimed standing for the purposes of the suit in his capacity as a farmer, not as a state officeholder. He is a Trump acolyte with a habit of posting inflammatory, racist memes on his office’s official Facebook account. When he campaigned for the commissioner post in 2014, he tapped former rocker/reality TV personality and longtime gun nut Ted Nugent as the co-chairman and treasurer of his campaign. Seldom seen without an enormous cowboy hat, Sid Miller owns a farm that received about $176,128 in USDA crop subsidies and disaster-relief funds between 1995 and 2020, according to the Environmental Working Group farm subsidy database.

Perhaps not coincidentally, AFL chose to launch its action in the US District Court for the Northern District of Texas, presided over by Judge Reed O’Connor. An active member of the influential conservative legal advocacy group the Federalist Society, O’Connor is best known for decisions like striking down a key provision in Obamacare and ruling against the rights of transgender people to freely use bathrooms. “The North Texas judge has emerged as something of a favorite for the Texas Attorney General’s Office, a notoriously litigious legal battalion known for challenging the federal government in cases and controversies across the country,” the Texas Tribune wrote in 2018.

His decision on AFL’s debt relief case upheld that reputation. In July, issuing an injunction against the program, O’Connor ruled that white farmers “face a substantial threat of irreparable harm absent a preliminary injunction” because they are “experiencing race-based discrimination at the hand of government officials.”

Similar lawsuits filed in two other states have also resulted in injunctions ordering the USDA to halt the debt relief program nationwide, putting it indefinitely on ice. The groups behind these other suits—the California-based Pacific Legal Foundation and the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty—also boast extremist, Trump-connected pedigrees. Both draw substantial support from the sprawling old-line conservative grantmaker the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, which has emerged as a major funder behind efforts to propagate Trump’s conspiracy myth that the Democrats stole the 2020 election from him. One of the Bradley Foundation’s board members is Cleta Mitchell, who stands at the “forefront of a group of lawyers and congressional allies echoing his [Trump’s] voter fraud claims,” CNN recently reported.

The Pacific Legal Foundation also gets funding from the Donor’s Trust, which a 2013 Mother Jones exposé described as the “dark-money ATM of the right,” flush with cash from the Koch brothers and other high rollers.

In short, Key and other farmers of color are being denied debt relief by some of the most sinister and well-funded forces in conservative politics.

While the primary culprit behind the suspension of debt relief for farmers of color is a fierce Trumpian legal and media backlash, some advocates say the Biden USDA, with Secretary Vilsack at its helm, bears its share of responsibility. Virginia farmer John Boyd, founder of the National Black Farmers Association, finds the USDA’s handling of the multi-billion-dollar debt relief package a disappointment. Vilsack “moved a little too slowly in getting the relief out,” he tells me. The drawn-out process “gave the right-wing organizations time to counteract.”

Boyd points out that under Trump, the USDA moved fast when doling out trade and coronavirus relief, which overwhelmingly flowed to white farmers. For example, on May 23, 2019, the Trump administration announced it would deliver $16 billion to farmers affected by the trade war. Within nine weeks, the agency had informed farmers of how to apply for the payments; and on Aug. 15, less than three months after the initial announcement, the money started going out.

The American Rescue Plan Act became law on March 11, 2021. If Biden’s USDA had rolled out the debt program as rapidly as Trump launched his farmer-aid efforts, the relief could have begun in early June—before the first court-ordered injunction freezing the program was handed down in Florida on June 23. Boyd added that there was little bureaucratic reason for such a long delay between the law’s passage and the program’s execution. The law specifically targets farmers of color with a “loan administered by the Farm Service Agency.” The USDA could quickly have used already-existing FSA data to generate a list of eligible farmers. “They knew who the farmers were, but they didn’t issue the payments,” he says.

Lawrence Lucas, president emeritus of the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, also criticizes the USDA for slow-walking the execution of the program. “Before a single case was filed in court, Tom Vilsack and USDA had the power to take care of the debt relief,” he says.

USDA spokeswoman Kate Waters disputed Boyd’s and Lucas’ assessment of the rollout. The department “took swift action to implement the program and mailed letters to eligible farmers and ranchers,” she wrote in an email.

The future of debt relief for a class of farmers who endured decades of racist treatment by the USDA now hangs on two delicate threads.

The first one is legal. On Oct. 12, 2021, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, the nonprofit supporting Black farmers that Key works with, filed a motion to intervene as a defendant in the Texas case, the one backed by Stephen Miller’s group. If the judge accepts the motion, the federation’s lawyers will join the USDA in arguing the case as it proceeds. In their motion, the group makes a powerful case that past USDA racism justifies debt relief specifically for farmers of color—a point the federation’s legal team can perhaps be expected to make more forcefully than the USDA’s own, because its members, many of whom have loans with the department, have a direct stake in the outcome.

Theoretically, such arguments hold water under US law, according to Sheryll Cashin, a law professor at Georgetown University, and the author of the new book White Space, Black Hood: Opportunity Hoarding and Segregation in the Age of Inequality. “Race-conscious public policies … can be legally justified, depending on the context,” she wrote in an August 2021 Politico op-ed. “Under existing legal precedent, the government has a compelling interest in remedying racial discrimination and preventing its perpetuation.” The USDA’s loan program, with its “history of pro-white and anti-Black policies,” falls under that rubric, and a program designed to address its wrongs “ought to pass constitutional muster,” she added. And “that is precisely what Congress did in enacting the farmers’ debt relief program.”

But being right doesn’t guarantee legal success, she acknowledged: “If the white farmers’ lawsuits were to be taken up by the Supreme Court, with its current conservative majority, the prospects for the debt relief program’s survival are grim.”

The other glimmer of hope for debt relief lies in Congress. Progressives like Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), who helped get the debt-relief provision into the American Rescue Plan Act, are trying to redo it in a more expansive way, in the Build Back Better Act currently under fierce negotiation on Capitol Hill. The idea would be to broaden the range of “socially disadvantaged” farmers who could receive relief, removing racial categories and opening it to struggling white farmers. The latest public framework of the bill, released by Biden on Oct. 28, includes “full and partial debt forgiveness” for “economically distressed borrowers and underserved farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners in high-poverty areas.”

According to Lucas, if passed in that form, Build Back Better would “provide debt cancellation for 91 percent of the 3,100 Black farmers who currently have debt with USDA.” And the absence of race-based language would likely shield it from legal challenge from the likes of American First Legal and other right-wing groups.

Cornelius Key launched his career as a farmer 30 years ago in part to redeem the struggles of his father. “One thing I wanted to do is to try to lease land so that my father could come along with me, rather than working a year for nothing,” he says. Key has succeeded beyond that dream, having come to own his own land—which his father, now 83, helps him work. “He’s retired three times, but he still [occasionally] drives a tractor, just like I do,” Key says.

Forgoing the obligation of annual debt payments to the USDA would stabilize their operation. It would put them in a position rarely seen by Black farmers in America.

“You’d be able to try to do things that you could not do before,” he says. “You’d hit a position to have some extra money to maybe buy some new equipment, or even purchase some land or some livestock—you’d have, you know, an opportunity.”

Images from left: Olivier Douliery/Abaca/Sipa USA/AP; Robert Hoetink/Getty