credit: Mother Jones illustration; Getty

In March of 2009, people in the rural Mexican village of La Gloria started coming down with a nasty respiratory infection. The town, located in the state of Veracruz, sat 5 miles from an industrial-scale hog farm. Within a few weeks, clusters of this rapidly progressing respiratory disorder arose among Mexico City residents. Researchers soon identified the bug as a “novel swine flu.” It quickly jumped to the United States and spread worldwide, and in June, the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, the first time it had done so since the deadly avian flu outbreak of 1968.

The 2009 swine flu strain didn’t turn out to be as deadly as originally feared. Although indeed novel, it was similar enough to older flu strains that about a third of people over 60—the most vulnerable population—had preexisting antibodies to the virus, helping them shake it off. Even so, it killed more than 284,000 people around the world, including at least 12,469 Americans.

We might not be so lucky next time. As the COVID-19 crisis lingers with no end in sight, it’s no fun to think about other emerging contagions that could be coming our way. But given the gaping holes the coronavirus fiasco has exposed in our infectious-disease response systems, it seems prudent to squarely face what’s coming down the pike—in hopes we can prepare to do better.

The likely source of the next pandemic is all around us: It’s the same one that triggered the 2009 scare. Industrial-scale hog and chicken farming—innovated in the United States and rapidly spreading globally—provides an ideal environment for the evolution and transmission of novel pathogens, especially influenza, that can infect people. (Cattle generally aren’t susceptible to human-adapted flus.)

“Another influenza pandemic occurring at some stage of the future is exceedingly high,” said Richard Webby, professor of infectious diseases at Memphis-based St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals. “The chances that it’ll come from some sort of farmed animal—my personal opinion is, that’s high as well.”

Gregory Gray, a professor of medicine, global health, and environmental health at Duke University and an expert on animal-to-human disease transmission, is even more direct. His biggest worry for the next viral pandemic? “Influenza A viruses that originate in pigs,” he said. “Hands down.”

The 2009 flu scare inspired the US government to ramp up its effort to monitor factory-scale farms for new pathogens, Gray added. But its surveillance was limited from the start, and in recent years has dwindled.

Pigs have a special capacity to incubate new viruses. Although birds are hosts to many kinds of influenza, avian flus don’t bounce easily to humans. There have been some exceptions: The 1997 H5N1 outbreak in Hong Kong sickened at least 18 people and killed six. But that event, as well as smaller outbreaks since, was relatively easy to control, because once the pathogen invaded the human immune system, it didn’t show much ability to spread person-to-person. Most infections involved people who had been in direct contact with birds.

Hogs are different. While pure swine flus don’t jump easily to humans, pigs can catch flu viruses that are from birds and humans, and then pass them back and forth. When more than one flu virus has infected a single host, the viruses have the sinister ability to swap genes, a process researchers call “reassortment.” Like DJs creating something new by grabbing and combining snippets from old vinyl records, flus use the bodies of pigs to make the viral equivalent of a mixtape. If a pig catches an avian flu and a human flu at the same time, the two viruses can morph into novel strains that contain swine, human, and avian genetic material, with the potential ability to infect all three species.

That’s why many epidemiologists call hogs “mixing vessels” for flu strains; they provide a host in which avian- and swine-evolved flus can reach people. And since human immune systems have little exposure to bird flus, it can be quite dangerous for us when genetic traces of these bird flus invade our bodies through a strain that was reassorted inside of a hog.

So scientists were alarmed earlier this summer when Chinese researchers published a paper in the peer-reviewed US journal PNAS reporting that an “avian-like” swine flu strain had become pervasive in the nation’s vast hog operations, containing “all the essential hallmarks” of a virus that can cause a human pandemic. The team tested 338 workers who routinely come into contact with hogs and found that 10.4 percent had antibodies to the new strain, meaning they had unknowingly contracted and recovered from the virus. They also tested 230 people who aren’t associated with the hog industry and found antibodies in 4.4 percent of them. In other words, the virus is out there, infecting people and evolving; likely being swapped back and forth between workers and hogs.

The strain recently identified in China, known as G4 EA H1N1, is related to the H1N1 flu that caused the global pandemic in 2009. The 2009 strain contained genes from avian, swine, and human flus—a classic “triple reassortment.” It has also taken on avian genes through reassortment that makes it novel to our immune systems—meaning it could be very hard to fight.

The new flu hasn’t caused major problems yet; it hasn’t proven either highly contagious or particularly virulent. But that could change as it circulates among the workers and animals in China’s hog industry. The fact that it’s out in the world, the paper warns, “greatly enhances the opportunity for virus adaptation in humans and raises concerns for the possible generation of pandemic viruses.” The WHO’s Webby put it like this: “It’s a numbers game. These viruses throw out mutations every time they replicate, so the more chances the virus gets, the more interactions with humans, the more chance that one day the stars will align in the right order, the virus will get the right mutation, and take off.”

Changes in our eating habits and farming practices have dramatically ramped up pigs’ propensity to gin up new pathogens. Humans domesticated them at least 9,000 years ago, and we’ve probably been swapping flus with them ever since. But for almost that entire history, hog farming was essentially a backyard activity, with relatively few animals per operation, and broad genetic diversity in the population. The numbers game Webby describes exists when hogs are kept on a small scale, outdoors, with the herds largely isolated from each other. But what’s happening now is different.

Starting in the 1980s, US pork packers began to change their model, inspired by what the poultry industry had done decades before. Instead of buying hogs from small producers, meatpacking companies moved to a vertically integrated model, pushing to source their pigs from large, confined operations working under production contracts.

The shift turned the industry upside down. According to US Census of Agriculture figures, in 1982, 330,000 farms raised 55.4 million hogs. By 2017, just 66,000 farms were churning out more than 72 million pigs. In other words, 80 percent of US hog farms exited the business over that period even as total output jumped 21 percent—and so the average number of hogs per farm spiked from 168 to 2,000, a 12-fold increase. And that figure understates the scale of modern hog production. The 2017 Ag Census show that three-quarters of US hogs are raised on the 3,600 largest operations, each averaging more than 14,000 animals.

Today, an industrial-scale hog “barn” is an enclosed facility holding as many as 4,440 pigs. A typical operation consists of several of these buildings clumped together, each with ventilation systems that have the potential to suck up airborne flu pathogens from each barn and pass them to the barn next door.

China’s pork sector, the globe’s largest, is rapidly mimicking the US model, though it’s at an earlier stage of the trajectory. Between 1975 and 2013, growth in China’s pork consumption rose by a factor of eight. (Though this growth has flattened in recent years.) Giant factory facilities took the place of the micro-scale operations that had sustained the region for centuries. In 2000, 74 percent of Chinese pork production came from backyard farms. By 2015, household sources were providing just 27 percent of the nation’s domestic pork. The contribution from commercial farms with at least 1,000 hogs, meanwhile, tripled over that decade.

What could possibly go wrong? Rob Wallace, an evolutionary biologist with the Agroecology and Rural Economics Research Corps and author of Big Farms Make Big Flu, argues that the industrial animal farming model delivers a perfect habitat for flus to proliferate, evolve, mutate, and adapt—to essentially hack the numbers game for creating pandemic strains. Factory-scale farms provide a huge playground for human and avian flus to “trade multiple combinations of genetic segments,” he said. They’re “an explosive evolutionary accelerant.”

For most of the 20th century, the flus circulating among US pigs didn’t evolve much genetically, meaning our immune systems had plenty of time to adapt the ability to fight them off. It wasn’t until the 1990s—when the consolidation of US hog production was reaching a crescendo—that pig flus began to reassort wildly with human and avian flus and create new strains that can jump to people. In a prescient paper he co-authored with other researchers, published five years before the 2009 outbreak, the WHO’s Webby sounded the alarm. “The influenza reservoir in the United States swine population has thus gone from a stable single viral lineage” to a “dynamic viral reservoir containing multiple viral lineages,” making the US swine population an “increasingly important reservoir of viruses with human pandemic potential,” they wrote.

In addition to capitalizing on the sheer number of potential hosts breathing in each other’s exhalations and excretions in a modern hog facility, viruses also take advantage of the pigs’ genetic similarity. With a genetically diverse drove, some pigs will have a mutation in their immune systems that blocks infection, limiting the pathogen’s range. But “if you’ve got a couple thousand genetically similar hogs packed in a barn, then it’s all food for flu,” Wallace said. As the industry breeds hogs to deliver consistent, uniform pork products, the genetic diversity of hog populations erodes, and what Wallace calls an “important firewall” to developing pandemic flu strains crumbles.

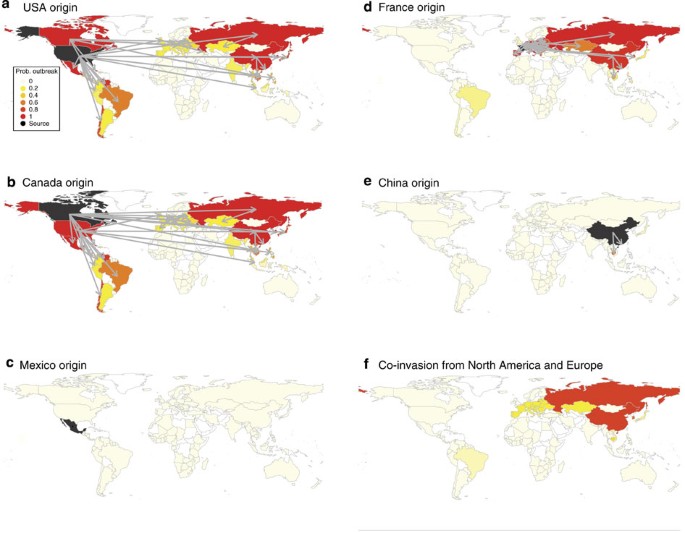

The workers who tend these pigs are prime targets for moving the virus into surrounding communities. And global trade ensures that the flu can travel the world. “The United States and Canada, the largest exporters of hog, are also the largest exporters of swine flu,” Wallace said. After the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994, Mexico began to dramatically scale up its own hog sector, leaning heavily on hogs imported from the United States and Europe. That flow of hogs and their attendant flus is the likely source of the 2009 triple-assorted pandemic strain, a 2016 analysis by US, Mexican, and European researchers shows. Wallace also points to a 2015 Nature study by a global team led by US National Institutes of Health researchers with a chart showing how flu bugs circulating on US farms disperse globally:

The US pork industry, for its part, asserts that the workers who tend hogs are unlikely to swap viruses with them, because hog farmers follow stringent biosecurity measures. “Modern US pig barns are designed specifically for pig health and safety,” Jason Menke, director of marketing communications for the National Pork Board, wrote in an email. Farmers wear special boots and clothing that stay in the barn. Many farms require caretakers to shower in special facilities attached to the barn, which “minimizes the chance that the pigs will be exposed to a pathogen that will make them ill.” Workers are also “encouraged” to wear personal-protective gear like masks to “protect themselves from both illness and injury working on the farm,” Menke wrote. He added that “sick leave policies encourage workers to stay home when ill to prevent unnecessarily exposure to other workers on site or to the pigs, since pigs can be infected with human influenza strains.”

But no biosecurity system is perfect, Wallace counters. In a 2015 paper looking at flu strains circulating on US pig farms, the National Institutes of Health and US Department of Agriculture researchers found that, despite the industry’s biosecurity efforts after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, industry workers “continuously” kept reinfecting the US hog herd with their flus. That meant hogs, mixing vessels for human and bird flus, got a steady infusions of human-adapted flus, free to re-assort and create novel strains that can infect people.

Wallace thinks that factory-scale livestock farming inherently generates viral pandemic threat, and should thus be dismantled—a view that gained political traction late last year when Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) floated a bill that would do just that. Booker’s proposal, which has since gained support from Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), remains unlikely to pass; the meat industry wields massive lobbying power in Washington. But as Ezra Klein recently reported in Vox, an “odd-bedfellows coalition” of animal-rights activists, economic populists, and small-scale farmers is rallying around it.

Mainstream university-based flu researchers are far more cautious about challenging the industry so directly. While Duke’s Gray insisted that the next pandemic might come from hogs, he does not advocate for banning industrial hog farming. “We have some of the safest and lowest-cost pork production in the world, and that’s wonderful,” he said. “And we are exporting that technology to many places around the world and they’re all shifting to large-scale farming—it’s the way to go to keep the hogs safe and produce low cost meat.”

He adds, however, that the pork industry and the US Department of Agriculture—which regulates the safety of meat production—aren’t doing enough to monitor the viral pathogens that can flourish on large hog operations. Through surveillance, researchers can see what’s out there and kick-start the development of human vaccines when novel strains emerge.

Back in 2010, in response to the previous year’s pandemic, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), a division of the US Department of Agriculture, launched a program to monitor and analyze flus circulating in the hog population. It’s an important but limited effort, Gray said. It relies on hog producers and veterinarians to swab animals showing flu symptoms (coughing, sneezing, runny nose, etc.) and send them in to USDA-affiliated labs. Gray characterized the program as “very spotty” because of its focus on “passive” testing, which relies on farmers to volunteer samples from sick animals.

Active testing, on the other hand, would randomly select samples from both visibly sick and asymptomatic animals. “There are influenza viruses that infect both humans and pigs [but] do not necessarily cause signs of infection in both,” he said. Similar to how people can be infected with COVID-19 and spread it without showing symptoms, pig flu often hides in animals that appear healthy. “Hence, I have long argued that passive surveillance among only sick pigs has the potential to miss novel emerging swine influenza viruses that may harm humans.”

The US hog industry is “really good” at detecting and preventing the spread of diseases that make pigs sick and lower production, Gray says. But viruses that don’t directly harm hogs—including those that might do worse damage to humans—”are tolerated, permitted to spread and to mutate.”

Worse still, Gray adds, as the 2009 flu pandemic recedes into the past, funding for the APHIS surveillance program—and the participation of hog farmers—has dwindled. In the agency’s most recent report on the program, released in July 2020, total samples received from farmers peaked in 2015 at 35,792 and had fallen to 3,098 in 2019. An APHIS spokesperson attributed the drop to changes made in 2016 to shift costs from the USDA budget on to hog farmers.

Meanwhile, influenzas aren’t the only viruses that circulate on hog farms. Coronaviruses do, too—like the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, which killed 10 percent of US hogs in 2013-14. (PEDV does not infect humans). As for SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus causing the current COVID-19 pandemic, a study released in June by Chinese researchers found that pigs are at least theoretically susceptible: They have lung and kidney cells that can be invaded by this particular pathogen. But laboratory attempts to infect pigs with it have so far not succeeded. “Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is still progressing and SARS-CoV-2 strains are constantly evolving,” they wrote, “we need to keep monitoring and evaluating the possibility of pigs to become intermediate hosts” of the pathogen.

Gray finds the prospect of hog-adapted SARS-CoV-2 daunting. As they do for flu, pigs could emerge as what disease researchers call a “reservoir” for the pathogen—a large host population that keeps the pathogen circulating, giving it more opportunity to infect people. “My chief concern is that the current SARS-CoV-2 virus adapts to commercial hogs, becomes amplified in them, and causes widespread infections, increasing the risk of the virus moving from the pigs to infect humans who have not been previously infected,” he said. He expressed an even darker possibility: The “remote chance” that if it does manage to enter the pig population, it could mutate into something different, yet another “novel coronavirus” that would require a whole new scramble for a vaccine.

“Honestly, I don’t know if we’re much better off post-2009 than we were pre-2009,” the WHO’s Webby said. Governments devoted resources to preventing the next big flu outbreak for a few years, but interest faded as the event receded into the past, he said. With COVID-19, “we’re really seeing for the first time in most people’s living memory the impacts these pandemics can have on society. So I’m hoping a silver lining from this will be more sustained resources into preparedness.”

Another possibility would be to rethink how we produce meat. The coronavirus pandemic has sparked calls to ban “wet markets”—the informal food markets that often include live wild animals, the possible point at which SARS-CoV-2 jumped from bats to people. As Wallace points out, globally, the biomass of the animals we eat—their sheer physical weight—is now “far greater” than their wild counterparts. “Planet Earth is basically Planet Farm,” he said. “When you populate the globe with cities of hogs and poultry, you’re going to generate novel pathogens” that confound human immunology, he added. Maybe the fear of another pandemic will finally force us to ramp down the scale of our livestock operations and adapt to diets that depend on way less meat.