Getty images

An occasional series about stuff that’s getting us through a pandemic. More here.

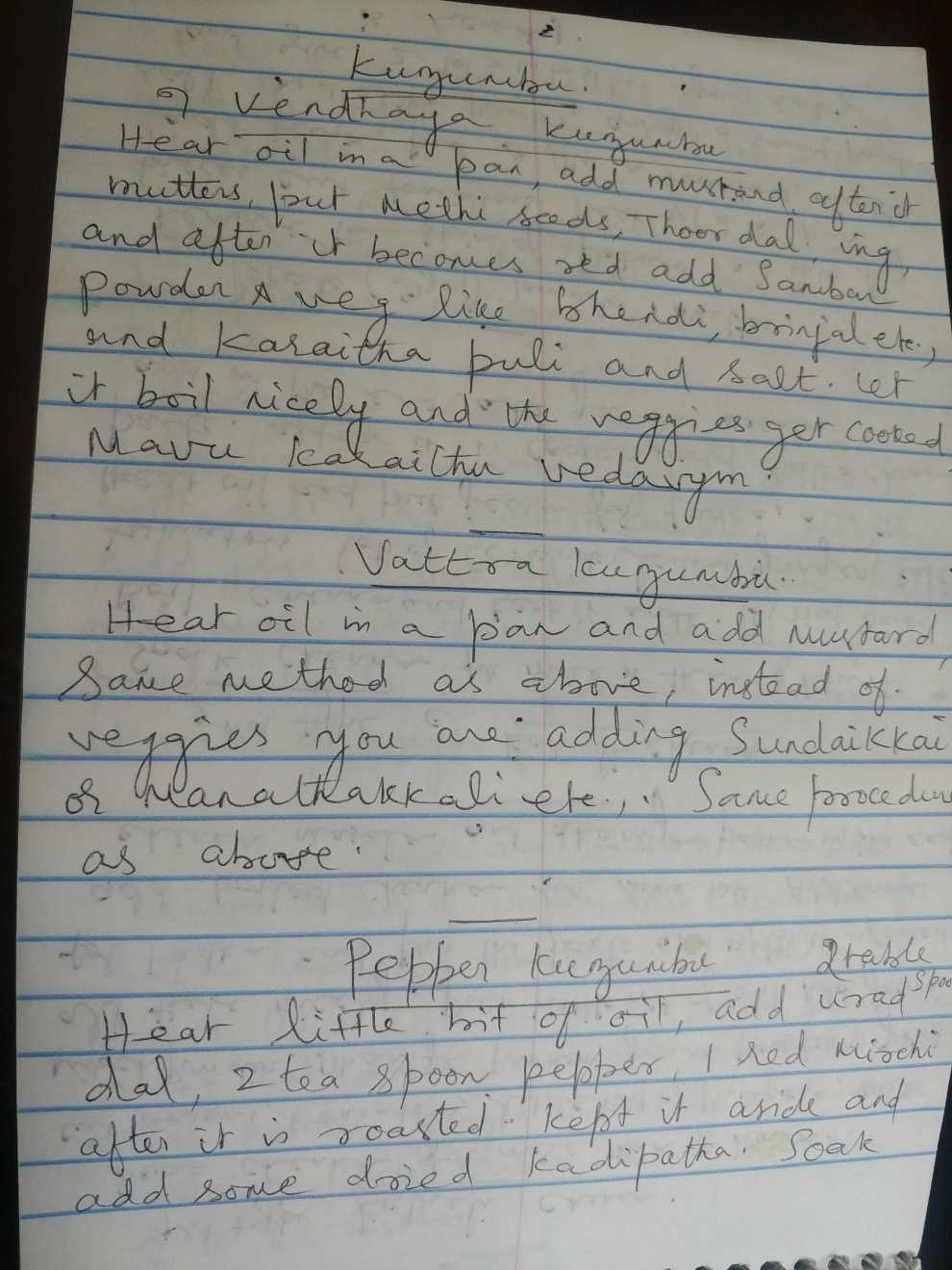

Vathal kuzhambu is a type of sambar from South India, brewed with tamarind juice, sesame oil, spices, and dried turkey berries. Its taste—at once sour, spicy, and sweet—reminds me of a time when my cousins and I would sit in a circle in our grandmother’s ancestral home in Chennai and take turns eating balls of yogurt rice dipped into the kuzhambu on hot summer afternoons.

Vathal kuzhambu has always been a favorite of mine, rarely available in restaurants, relatively unknown, but a household regular while I was growing up in India. It was a signature dish of my mom’s, one of many I’ve tried to master over the last few months.

Though the recipe is simple—boil tamarind and spices together, fry the dried berries in sesame oil and add the fried stuff to the boiled stuff—I never really tried to make it myself as an adult. Instead, I’d wait for my mom to make it during our annual get-together; or, if I really craved it, I’d use a concentrated version of the kuzhambu, available in stores, in the form of a paste. It’s not the same as the real thing freshly made from scratch, but for those who don’t know how to do the real thing, it was pretty darn good.

Vathal kuzhambu may have been the star of my South Indian cooking pleasures, but I have been making other dishes, too. I’ve made tamarind rice; kootu, a stew of lentils cooked with vegetables, ground coconut, red chilies, and black gram; and neemflower rasam, a soup-like concoction made with tamarind juice and dried flowers of the medicinal neem tree. (I was surprised to hear that rasam has been part of Chris Cuomo’s healing process from COVID-19; rasam is my comfort food, but it won’t cure you of the coronavirus.)

I wondered why I’d waited so long to cook these dishes. After all, the dried turkey berries and neemflowers, given to me by my mom, have been lying around in my pantry for years. The straightforward answer is probably that I was missing my mom and didn’t know when I’d see her next. She was supposed to visit me last month, but had to cancel due to the pandemic. My mom learned these rare, authentic, herby dishes from my grandmother, who lived till she was 91 years old and cured her (and our) little ailments using these recipes. She passed away recently, so maybe this was my way of honoring her. But still, my single-minded obsession with a cuisine I didn’t pay much attention to all my life was baffling to me.

We were part of the great Indian middle class, which meant that there was always food on the table, but there was no money to spend on things such as eating at restaurants (I can count on one hand the number of times we ate out during my entire childhood) or watching movies in a theater or taking vacations (the only vacations were to visit my grandparents). This ungratefulness for a mother’s home cooked food isn’t uncommon either. The show Yeh Meri Family on Netflix (the name translates to “This is my family”) depicts the Indian middle class, and the lead character, a 13-year-old boy, is super sulky because his mom cooks a gazillion dishes from scratch for his birthday and invites all his friends home instead of letting him go out to watch a movie. I can’t shake that image of his mom, drenched in sweat, laboring in a sweltering Indian kitchen. A lot of Indian moms, especially those of my mother’s generation, were stay-at-home moms or “homemakers” whose labor was unpaid and invisible and thus totally unappreciated.

For most of my childhood, I’d taken my mom’s food for granted. She was a stay-at-home mom in Mumbai who spent an inordinate amount of her time cooking fresh meals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The woman-in-her-30s-working-mom me is so grateful for that, but as a child, I only complained: Why can’t we go out to a restaurant like my friends? Do I have to eat these cold soggy idlis in my lunchbox everyday? Not that I didn’t go to South Indian restaurants or secretly enjoy the food. It was more like I feigned nonchalance, a cool distance, as if this was one of many things I liked, as if I didn’t care for it as much as I did. So as the world paused, I also paused to reflect. I realized my obsession had deeper roots in my identity as a woman and an immigrant. To know what I was coming back to, I had to know why I left in the first place.

If I was trying to escape being my mom, I was also trying to escape being a Tamilian. I have always been an outsider yearning to belong and “assimilate”—a Tamilian in Mumbai; an Indian in the United States. I remember a classmate in school, secure in his identity as a Mumbaikar, once mimicked the way we “Madrasis” (people who hail from the city of Madras, a pejorative term) ate with our hands. He licked his fingers and expressed disgust at how uncouth we were. In fact, there is some science to the idea that food tastes better when eaten with hands. Many cultures from South Asia, Africa and the Middle East do it. A girl from my neighborhood said that Tamil was so harsh on her ears that it sounded like stones clattering in a metal can. Of course, she didn’t care that Tamil is one of the oldest languages in the world, dating back 2000 years.

Later, a fellow journalist, a coffee connoisseur, shrugged his shoulders and declared that South Indian specialty coffee wasn’t high quality. It’s a cornerstone of Tamilian culture. I think it’s delicious, but only if you know how to make it right.

I am not saying this stuff to extol the virtues of my culture. My zealous, right-wing uncles do a fine job of that inside closed WhatsApp groups. I am saying it to illustrate how little we understand outsiders; how stereotypes and caricatures get things wrong; how even well-meaning people can sometimes reduce a culture to an aesthetic experience, to be judged on its distance from their norms.

I am used to these slights. I am adept at tucking them away at some corner of my mind. I am adept at picking my battles as every outsider is. Or at least I thought I was. As an immigrant, I relate less to Hasan Minahj and more to his dad, who asks him to forgive those who don’t know any better. In his Netflix special Homecoming King, Minahj talks about having the “audacity for equality,” a privilege that only a first-generation American would dare possess. As I reflect on my newfound obsession, I wonder if these incidents had induced a subconscious disregard for my heritage and food.

My mom’s cooking was a dominant part of her identity and if I wanted to pursue a life different from hers, with more financial independence and a fulfilling career, I thought I had to run away from what was so central to her being. But the pandemic is teaching me that I couldn’t just continue to rely on her to cook my favorite dishes; it may be a while before that can happen again. If I wanted to eat her dishes, I had to learn to cook them for myself and my child. It was time for me to become my mom.

There was a lesson in this about assimilation. It’s not about giving up or giving in, but giving, period. It’s about giving a part of you to the new world that you’re a part of in order to enrich and transform it. But to give, one has to own. In my case, I had to own my legacy. I had to acknowledge and accept the rich heritage that was already a part of me and that I in turn was a part of.

When my 3-year-old calls my vathal kuzhambu spicy and eats her pasta instead, I remain unperturbed. I know she’ll come around to appreciate it, even if it takes her some time. I came around, after all, even if it took me three decades.