When Michael Padilla was in elementary school in Albuquerque, New Mexico, his family couldn’t afford to send him to school with lunch money, so he worked extra hours mopping the school’s cafeteria to pay for his midday meal. Years later, when he became a state senator and learned that poor kids were still getting singled out in his home state, he was shocked. “In some schools they were literally stamping the arm of a child saying, ‘I need lunch money,'” Padilla said on a recent episode of our food politics podcast, Bite. “That sticks with some kids.” (Our interview with Padilla starts just before the 23-minute mark.)

So earlier this year, Padilla wrote a bill in conjunction with New Mexico Apple Seed, an anti-hunger nonprofit, to outlaw practices that shame kids who can’t fork over for their meals at school. The Hunger-Free Students Bill of Rights Act, which passed in early April, requires that all students have access to the same food and that school officials help low-income families sign up for free school lunches. Since it passed, more than 20 state representatives have contacted Padilla to create similar laws in their states, and a national Anti-Lunch Shaming Act was introduced Congress in May.

While schools grapple with paying these debts, private parties often fill the gap. Cafeteria workers have been known to pay for students’ lunches, and recent reports have surfaced of donors taking care of the outstanding bills. For instance, New York-based writer Ashley C. Ford launched a Twitter campaign last December and inspired people to donate thousands of dollars towards paying off low-income students’ lunch debts.

Lunch shaming certainly isn’t the first time school meals have become the source of controversy. Here’s a look back at some of the most notable battles about what kids eat at school and who pays for it.

1921: After experimenting with serving a midday meal to students in one of the country’s earliest school lunch programs, board members in St. Louis decide it’s too costly, declaring it illegal to spend public funds to buy food.

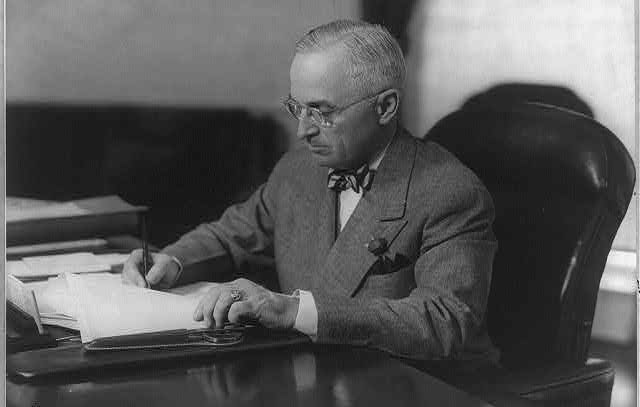

Library of Congress

1946: When labor and supplies begin slowly disappearing during World War II, many schools stop serving lunch. To mandate that kids are healthy and well fed, President Harry S. Truman signs the National School Lunch Act, making school lunch an official program of the federal government.

Library of Congress

1957: Minnijean Brown is one of the nine African American students sent to Little Rock Central High School during the school integration movement. A group of white boys begin teasing Brown in the cafeteria one day, and she spills her bowl of chili on them. Brown receives a six-day suspension.

1960: In Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird, character Walter Cunningham Jr. shows up to school with ringworm and without lunch. Scout sticks up for him to the teacher: “You’re shamin’ him, Miss Caroline. Walter hasn’t got a quarter at home to bring you.”

Mid-1960s: The School Lunch Program initially relies on a combination of state funding as well as student fees, leaving many poor African American students in Southern states without lunch. In Alabama, Georgia, Virginia, and Mississippi, only a quarter of black students get lunch, compared with 50 percent of white students.

1969: The Black Panther Party serves grits, eggs, and toast out of St. Augustine’s Church in Oakland, California, out of its own Free Breakfast for Children Program. Some party members claim the federal government ramped up its own breakfast efforts after seeing the Black Panther Party’s success fighting poverty by servings kids breakfast.

1975: While researching junk foods available in Arkansas’s school cafeterias, a PTA group uncovers a statewide price-fixing scheme organized by dairy companies. In 1977, the dairies are handed criminal indictments. In 1980, Little Rock School District files a lawsuit against the dairies; the case settles for nearly $2.5 million.

1978: “Tofu Queen” Thelma Dalman continues her progressive menu planning for a school lunch program in Santa Cruz, California, by serving tofu alongside the cafeteria’s house-made whole grain bread and other sugar-free, chemical-free menu items. But it wasn’t until 2012 that the US Department of Agriculture approved soybean protein as an alternative to meat.

1979: The US Department of Agriculture rules that lunches sold in cafeterias only need “minimum nutritional value.” One official said that even if a candy bar has one nut in it, “we feel it is above our minimum nutrient standards.”

1980: Inspectors recover 13 of 20 tons of pesticide-contaminated pork before it arrives to school kitchens in Arkansas and Louisiana. As for the remaining seven tons? “We have every reason to believe…it was eaten,” the USDA’s assistant secretary told the Washington Post.

1981: $1.5 billion is cut from the school lunch program under the Reagan administration. In order to meet federal nutrition standards, the administration proposes to classify ketchup as a vegetable in school meals. The press has a heyday, and, as reported by author Marion Nestle, Republican Senator John Heinz (of Heinz ketchup) said at the time: “Ketchup is a condiment. This is one of the most ridiculous regulations I ever heard of, and I suppose I need not add that I know something about ketchup and relish–or did at one time.”

1990’s: Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and Subway set up shop in just over 11,000 school cafeterias. In coming years, McDonald’s markets to school kids by offering gym class videos starring Ronald McDonald, work training programs for teens, and free breakfasts on testing days in local schools.

Mid-1990’s: The media increasingly reports on the risk of death posed by peanut allergies. In 1995, the Wall Street Journal publishes an article with the headline “Peanut Allergies Have Put Sufferers on Constant Alert,” and by 1998 some schools have banned peanut butter from the cafeteria.

2010: President Barack Obama signs the Healthy, Hunger-Free School Kids Act, with aims to decrease sodium levels in school lunches from 1,230 to 935 milligrams by 2020; increase the number of whole grains; and require kids to take fruits and vegetables as a part of their school provided lunch. “Had I not been able to get this passed, I would be sleeping on the couch,” Obama jokes. Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign, which emphasizes healthy meals and daily exercise, becomes one of her most signature contributions as first lady.

2012: ABC News and other media outlets report on “pink slime,” finely textured cow trimmings doused with ammonia used to bulk up burger mix. Beef Products Inc. sold the substance to fast-food chains, grocery stores, and school lunch programs as a safer alternative than conventional ground beef. But in preceding years, the National School Lunch Program had found that pink slime tested positive for salmonella at a rate of four times higher than other school lunch suppliers. Beef Products Inc. sued ABC News, claiming the outlet misled audiences. The case later settled for more than $177 million.

2015: A Los Angeles-area school district accountant is sentenced to five years in prison for stealing $1.8 million in school lunch money after surveillance videos show her shoving cash into her bra.

March 2017: A second-grader in Arizona arrives home with “LUNCH MONEY” stamped on his arm. A cafeteria employee put it there when his account revealed he still owed 75 cents on his school lunch bill. In Pennsylvania, a student with an outstanding balance on her school lunch bill reaches the front of the line and is forced to toss the contents of her tray. In April, New Mexico becomes the first state to outlaw “school lunch shaming” by schools or cafeteria workers.

My friend's son came home from school Thursday with a stamp on his arm that said "LUNCH MONEY" because his account was low.

— speaking part fine (@juanyfbaby) April 1, 2017

2017: The Trump administration rolls back staples of Michelle Obama’s Healthy School Lunch policies, such as requirements to reduce sodium and incorporate whole grains. A nationwide reduction in school lunches’ sodium was meant to take effect in 2017; that timeline has been dropped.