A vast Lake Erie algae bloom returns, captured by a NASA satelite on July 28. <a href="http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=86327">NASA</a>/Earth Observatory

The citizens of Toledo, Ohio, have embarked upon their new summer ritual: stocking up on bottled water. For the second straight year, an enormous algae bloom has settled upon Lake Erie, generating nasty toxins right where the city of 400,000 draws its tap water.

It’s a kind of throwback to Toledo’s postwar heyday, when the Rust Belt’s booming factories deposited phosphorus-laced wastewater into streams that made their way into Lake Erie, feeding algae growths that rival today’s in size. But after the decline of heavy industry and the advent of the Clean Water Act, there’s a new main source of algae-feeding phosphorus into the beleaguered lake: fertilizer runoff from industrial-scale corn and soybean farms. (Background here.)

As I reported last August, the trouble is that freshwater blooms produce a toxin called microcystin, which can trigger nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, severe headaches, fever, and even liver damage. For three days last year, microcystin in Toledo’s water exceeded federal limits, and the city had to urge residents not only to avoid drinking it, but also to use bottled water to wash dishes and bathe infants.

Toledo has since implemented an early warning system near its water intake for monitoring potential microcystin contamination in Lake Erie—one, it hopes, will prevent a repeat of last year’s don’t-drink-the-water event by giving the city time to run its carbon-filtration system when toxin levels at the source spike. The filtration system does work to push microcystin levels to below the legal limit, said Justin Chaffin, research coordinator for Ohio State University’s Ohio Sea Grant program, which coordinates efforts to monitor the lake‘s algae blooms. The problem, he said, is that it costs thousands of dollars per day to run.

For the second time in a week, the city placed the water under “watch” status on Saturday. “Microcystin is detected in the intake crib in Lake Erie, but not in the tap water,” a city notice states. “Our water treatment process is effectively removing the microcystin.” Not fully reassured after the shock of last year’s nasty surprise, Toledo residents are clearing retail shelves of bottled water, forcing some stores to limit how much consumers can buy at once.

A spokesperson for the Toledo water utility declined to estimate how much the city has spent to implement and run its early warning system or the carbon-filtration system. In 2014, Toledo newspaper the Blade reported the city “has spent $3 million a year battling algae toxins in recent years,” and $4 million in 2013. Despite the outlays, residents are understandably skittish about Toledo water.

Toledo’s fertilizer-haunted water supply is hardly an isolated case. Similar situations persist throughout the Corn Belt, from Ohio in the east to Nebraska in the west. To grow the great bulk of corn and soybeans that fuel our food system, the Corn Belt uses massive amounts of fertilizer—and it doesn’t stay put. For example, Iowa’s Department of Natural Resources has had to issue 131 advisories since 2006—and 17 so far this year—warning people to keep themselves and their pets out of lakes made toxic by these phosphorus-fed blooms. Ohio has eight such warnings active, apart from the drama in Toledo.

Then there’s the related problem of another chemical fertilizer used on farms, nitrogen. It enters drinking water supplies in the form of nitrate, which can restrict the blood’s ability to carry oxygen and is thus particularly hazardous to infants. Regular low-level exposure to nitrate has been associated with birth defects as well as cancers of the ovaries and thyroid. The waterworks utility of Des Moines, Iowa, claims to have spent $1.5 million since December 2014 keeping nitrate levels below legal limits, and claims it needs to invest as much as $183 million in new filtration equipment to battle the problem going forward. Back in June, Columbus, Ohio, had to warn pregnant women and babies to avoid the tap because nitrate levels had spiked above legal limits. The same thing has forced the Nebraska town of Prosser to warn its residents away from tap water for more than a year—and to raise $84,000 to put a reverse-osmosis filter in every kitchen.

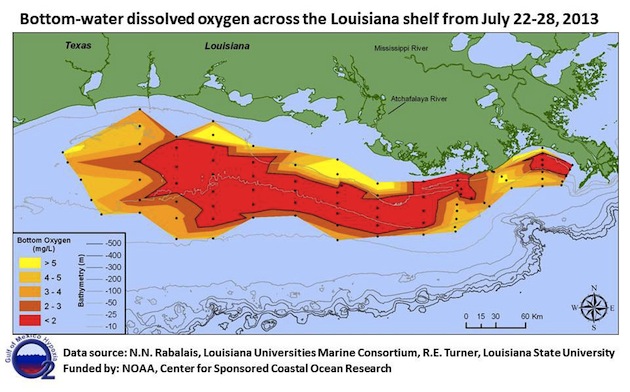

Of course, the Corn Belt’s fertilizer runoff doesn’t just wreak havoc within the region. The great bulk of these pollutants make their way to the Gulf of Mexico through the Mississippi River, where they feed one of the globe’s largest annual fish-killing algae blooms. According to the latest National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projections, this year’s version will be just “average” in size—blotting out sea life in area of some 5,400 square miles, roughly the area of Connecticut.

Earlier this year, fed up with its own mounting filtration bills, the water utility in Des Moines sued three upstream farming districts to force the federal government to regulate their runoff under the Clean Water Act (which exempts most agriculture operations because they’re “non-point” pollution sources). The suit, which won’t be heard in federal court until next year, will be closely watched throughout the Corn Belt. Meanwhile, the Toledo utility spokeswoman declined to comment on whether the city was considering taking similar action.