<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&autocomplete_id=143440818557613360000&search_tracking_id=tZJx8fHBafVqkz9v0OYxJw&searchterm=dirty%20faucet%20water&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=140137948" target="_blank">TRIG</a>/Shutterstock

One day last August, residents in Toledo, Ohio, received a stark warning from city officials: Don’t drink your tap water, don’t wash the dishes in it, and don’t bathe your kids in it. This year, it’s the people of Columbus, 150 miles to the south, who received a jolt of bad news: In a large swath of the city and its suburbs, pregnant women and babies younger than six months of age have been advised to avoid the tap. In a warning well designed to titillate headline writers, another group landed on the don’t-drink-the-water list: Viagra users.

The advisory “will remain in effect until further notice,” the City of Columbus website states. The Columbus Dispatch reported that it could “last weeks.”

What gives? Toledo and Columbus are surrounded by industrial-scale corn, soybean, and hog farms, and in both cases, runoff from these operations fouled the water supply. In Toledo, the culprit was phosphorus finding its way from farm fields into Lake Erie, from which the city draws its water. Excessively high phosphorus levels fed a massive algae bloom, from which toxins seeped into the municipal water supply.

In Columbus, the problem is nitrate, from nitrogen fertilizer that leaches out of farm fields and into streams and rivers. Nitrates also concentrate in hog manure, which is also applied to farm fields and is prone to leaching. Nitrates in the water emerging from one of the city’s main water-treatment facilities, called Dublin Road, have exceeded the federal limit of 10 parts per million.

That’s bad, because nitrates are linked to a range of health problems at low exposure levels: They impede the blood’s ability to carry oxygen—a characteristic that’s particularly threatening to infants. They’ve also been linked to elevated rates of birth defects as well as cancers of the ovaries and thyroid. As for Viagra users, they should avoid the water because the drug interacts with nitrates in a way that can cause a dangerous drop in blood pressure.

On its website, the City of Columbus bluntly states the cause of the nitrate spike: “Elevated nitrate levels are primarily a result of fertilizer and agricultural runoff within the 1,000 square mile Scioto River watershed—80% of which is agricultural.”

The water-treatment plant in question currently lacks the ability to filter out nitrates. The city is spending $35 million on an ion-exchange treatment facility that, “when completed in 2017, will allow the plant to more effectively treat nitrate events such as this one,” its website states. Nitrate advisories like the current one have been common over the years, reports the Dispatch.

Nitrate-laced water is a problem throughout the Corn Belt, those upper Midwest states with high concentrations of ferilizer-intensive corn farming and large-scale hog-production facilities. A 2008 survey found that about half of Iowa’s private wells had measurable levels of nitrate, and in 12 percent the chemical turned up above the Environmental Protection Agency’s limit. And in Des Moines, the city’s water department is suing upstream farm-drainage districts, demanding that they be regulated under the Clean Water Act. To protect its residents from over-the-limit nitrate levels, Des Moines Water Works has had to run its nitrate-removal facility for a record 111 days this year, at a cost of about $7,000 per day. The filtration system dates to 1991, Des Moines Water Works claims, and will soon need to be replaced, which will result in a bill to rate payers as high as $183 million.

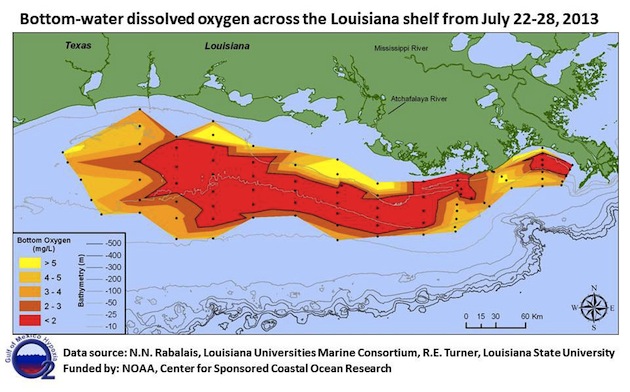

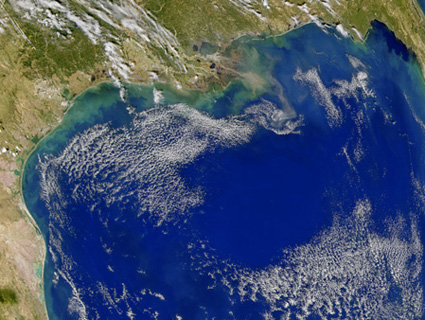

Meanwhile, the bulk of nitrates exiting the Corn Belt’s farms wind up in the Gulf of Mexico, where they feed a vast annual algae bloom that creates a Connecticut-sized oceanic dead zone.

The cases of Toledo, Columbus, Des Moines, and the Gulf share a theme: They represent major costs and liabilities of industrial-scale agriculture that take place off the books of the benefiting companies and are literally flowing downstream.