<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&searchterm=farm%20workers&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=54017278">mikeledray</a>/Shutterstock

When most of us think of Mexican food, we visualize tacos, burritos, and chiles rellenos. But we should probably add cucumbers, squash, melons, and berries to the list—more or less the whole supermarket produce aisle, in fact. The United States imports more than a quarter of the fresh fruit and nearly a third of the vegetables we consume. And a huge portion of that foreign-grown bounty—69 percent of vegetables and 37 percent of fruit—comes from our neighbor to the south.

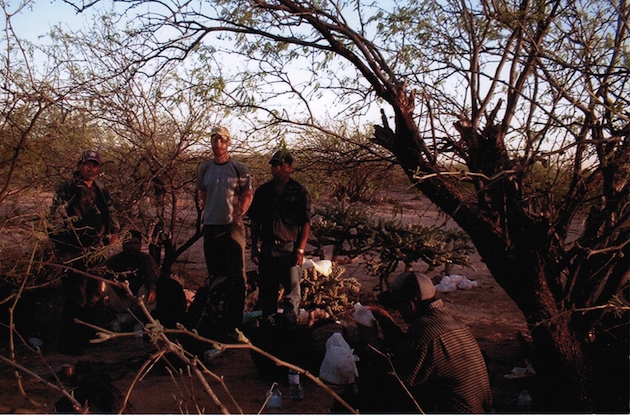

Not surprisingly, as I’ve shown before, labor conditions on Mexico’s large export-oriented farms tend to be dismal: subpar housing, inadequate sanitation, poverty wages, and often, labor arrangements that approach slavery. But this week, workers in Baja California, a major ag-producing state just south of California, are standing up. Here’s the Los Angeles Times: “Thousands of laborers in the San Quintín Valley 200 miles south of San Diego went on strike Tuesday, leaving the fields and greenhouses full of produce that is now on the verge of rotting.”

In addition to the work stoppage, striking workers shut down 55 miles of the Trans-Peninsular Highway, a key thoroughfare for moving goods from Baja California to points north, the Mexico City newspaper La Jornada (in Spanish) reported after the strike started on March 17.

The blockade has been lifted, at least temporarily. But the “road remains hard to traverse as rogue groups stop and, at times, attack truck drivers,” the LA Times reports. And the strike itself continues. The uprising is starting to affect US supply chains. An executive for the organic-produce titan Del Cabo Produce, which grows vegetables south of the San Quintín Valley but needs to traverse it to reach its US customers, told the Times that the clash is “creating a lot of logistical problems…We’re having to cut orders.” And “Costco reported that organic strawberries are in short supply because about 80% of the production this time of year comes from Baja California,” the Times added. The US trade publication Produce News downplayed the strike’s impact, calling it “minor.”

Meanwhile, the strike’s organizers plan to launch a campaign to get US consumers to boycott products grown in the region, mainly tomatoes, cucumbers, and strawberries, inspired by the successful ’70s-era actions of the California-based United Farm Workers, headed by Cesar Chavez, La Jornada reported Tuesday. And current UFW president Arturo Rodriguez has issued a statement of solidarity with the San Quintín strikers.

Such cross-border organizing is critical, because the people who work on Mexico’s export-focused farms tend to be from the same places as the people who work on the vast California and Florida operations that supply the bulk of our domestically grown produce: the largely indigenous states of southern Mexico. And the final market for the crops they tend and harvest is also the same: US supermarkets and restaurants.

In a stunning four-part series last year, LA Times reporter Richard Marosi documented the harsh conditions that prevail on the Mexican farms that churn out our food. He found:

- Many farm laborers are essentially trapped for months at a time in rat-infested camps, often without beds and sometimes without functioning toilets or a reliable water supply.

- Some camp bosses illegally withhold wages to prevent workers from leaving during peak harvest periods.

- Laborers often go deep in debt paying inflated prices for necessities at company stores. Some are reduced to scavenging for food when their credit is cut off. It’s common for laborers to head home penniless at the end of a harvest.

- Those who seek to escape their debts and miserable living conditions have to contend with guards, barbed-wire fences, and sometimes threats of violence from camp supervisors.

- Major US companies have done little to enforce social responsibility guidelines that call for basic worker protections such as clean housing and fair pay practices.

As for their counterparts to the north, migrant-reliant US farms tend to treat workers harshly as well, as the excellent 2014 documentary Food Chains demonstrates. The trailer, below, is a good crash course on what it’s like to be at the bottom of the US food system. In honor of National Farm Worker Awareness Week, the producers are making it available for $0.99 on iTunes. And here‘s an interview with the film’s director, Sanjay Rawal, by Mother Jones‘ Maddie Oatman.