See that gash in the land? Until heavy rains hit in May 2013, it was filled with topsoil. It's an "ephemeral gully," and Iowa is full of them after hard rains. All photos from Environmental Working Group's 2013 report <a href="http://www.ewg.org/research/spring-storm-batter-midwest-soil-and-streams">Washout.</a>

Last year, after a record drought in 2012, Iowa experienced the wettest spring in its recorded history. The rains triggered massive runoff from the state’s farms into its creeks, streams, and rivers, tainting water with toxic nitrate from fertilizer. Nitrate levels in the state’s waterways reached record levels—so high that they emerged as a “real issue for human health,” Bob Hirsch, a hydrologist for the US Geological Survey, told the Associated Press.

The event illustrated two problems facing Iowa and the rest of the nation’s topsoil-rich grain belt. The first is the challenge of climate change: how to manage farmland in an era when weather lurches from brutal drought to flooding, as it likely will with increasing frequency. The second, related challenge is the largely invisible crisis of Iowa’s topsoil, which appears to be eroding at a much higher rate than US Department of Agriculture numbers indicate—and, more importantly, at up to 16 times the natural soil replacement rate.

I got that disturbing assessment from Richard Cruse, an agronomist and the director of Iowa State University’s Iowa Water Center. Cruse’s on-the-ground research has shown a particular kind of soil erosion clearly connected to last year’s heavy rains. Cruse told me that with current methods, the USDA measures a kind of soil loss called “sheet and rill erosion,” wherein water washes soil away in small channels that form at the soil surface during rains. Under that measure, Iowa farmland loses an average 5.2 tons of topsoil per acre every year, according to the USDA’s latest numbers, which are from 2007.

The USDA sees five tons per acre as a “magic number,” Cruse said, because it’s generally accepted to be the rate at which soil renews itself. So the prevailing view has been that “if we can limit erosion to five tons per acre, we can do this forever,” Cruse said. But he added that the “best science” (explained here) indicates that the real sustainable erosion rate is closer to a half ton per acre—meaning that even by the USDA’s own limited measure, Iowa’s soils are eroding much faster than they can be replaced naturally.

But here’s where we get to the scary part. Using stereo-photographic techniques, Cruse and his team have been measuring a different form of erosion that occurs through what are known as “ephemeral gullies”—that is, large gashes in farm fields formed by water during heavy rains, bearing soil rapidly away and dispersing it into streams and rivers. This kind of erosion is not included in conventional soil-loss measures, and as a result, the USDA is “way underestimating” erosion in Iowa, he said.

Cruse’s team has not collected data long enough, nor analyzed it thoroughly enough, to say exactly how much soil is being surrendered in this way. But he added that he “could say with a lot of confidence” that ephemeral gullies are carrying away on average an additional 2.5 to 3 tons of soil per acre—bringing the grand erosion total as high as 8 tons per acre, 60 percent higher than the USDA’s sustainable threshold of 5 tons and 16 times higher than the 0.5-ton limit that Cruse says is more scientifically valid.

Ephemeral gullies represent not only an alarming disappearance of productive soil; they also mean a concentrated transfer of farm chemicals into waterways, where they feed algae blooms and get into municipal drinking water. That’s because when an ephemeral gully appears one growing season, farmers push fresh topsoil into the gullies. That topsoil, heavily treated with fertilizer and herbicides, is just the kind that causes the most water-quality damage when the next ephemeral gully forms, Cruse said. It’s a startling image: The gullies are essentially pipelines, periodically filled by farmers, that move prime soil from fields into streams.

And there’s a feedback loop operating here, Cruse said—as Iowa’s farmland loses soil, it also loses the ability to trap water, because soil acts as a sponge. That makes it more prone to flooding, and more likely to sprout ephemeral gullies.

In the wake of last year’s heavy rains, the Environmental Working Group filed a great report called “Washout” on the damage done to Iowa’s soils, building on its landmark 2011 study on Iowa’s erosion problem, “Losing Ground.” EWG looked at data from ISU’s Iowa Daily Erosion Project, and found that in less than a week, farmland in 50 townships covering 1.2 million acres suffered average erosion of more than 5 tons per acre—and that in 15 of those townships fields suffered average erosion of 7.5 to 13 tons per acre. (The recognized, and probably overstated, “sustainable” rate of erosion, recall, is five tons per year.)

And here’s the catch: The Iowa Daily Erosion Project doesn’t have the technology to account for ephemeral gullies. In the wake of the May storms, the EWG researchers “drove a random loop” through seven counties around EWG’s Midwest office in Ames. They found “gullies scarring field after field,” as well as roadside ditches “full of mud and polluted runoff—a very bad sign for Iowa’s already polluted streams.” (If you don’t believe that “field after field” had formed gullies, check out the EWG researchers’ slideshow from their trip, which I’ve plunked down below.) So, erosion from last year’s rains was “actually worse—likely far worse—than even the IDEP estimates,” EWG concludes.

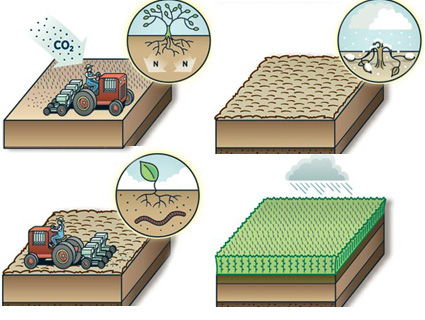

I asked Cruse, whose team is creating tools that can help document gully erosion, what farming practices could stem the hemorrhaging of Iowa’s soils. He pointed to winter-season cover crops, which have the twin virtues of (a) building organic matter in soil, giving it more capacity to sponge up water; and (b) providing a cover, a mat of plant matter that shields soil from being disturbed and dislodged by heavy rains. Both help keep soil in place and prevent gullies. (For a deeper dive into cover crops, see my 2013 piece on the innovative Ohio farmer David Brandt.)

Cruse also mentioned reintegrating grazing animals into Iowa’s fields. Maintaining pastures for livestock means an abundance of perennial grasses, which act like cover crops and keep soil in place—granted, of course, that the animals are properly rotated and not allowed to overgraze, which also degrades soil.

I also asked him how long Iowa’s farmers could go on pushing their soils for maximum corn and soy production without integrating cover crops and livestock on a much larger scale than is happening now. He said that Iowa’s status as an agriculture powerhouse relative to other farming regions worldwide will likely continue for a while, because most of the globe’s farmland is experiencing equal or even greater soil degradation. Not the most comforting answer!

He added he can’t pinpoint the year “when we cross a ‘game over’ condition.” But he could say with certainty that the “impact of soil erosion is a gradual decline in production potential and, probably even more important, soil resilience—the capacity of soil to supply needed water and nutrients under weather- or climate-stressful conditions.”

After talking to Cruse and reading the EWG report, I reread the first chapter of University of Washington ecologist David Montgomery’s terrific 2007 book Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations. “With just a couple feet of soil standing between prosperity and desolation, civilizations that plow through their soil vanish,” Montgomery wrote.

For a graphic immersion into what Iowa looked like after last year’s storms, check out Environmental Working Group’s fantastic slideshow: