A cattle feedlot near Rocky Ford, Colo. <a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cattle_Feedlot_near_Rocky_Ford,_CO_IMG_5651.JPG">Billy Hathorn</a>/Wikimedia Commons

Meatpacking giant Tyson recently grabbed headlines when it announced it would no longer buy and slaughter cows treated with a growth-enhancing drug called Zilmax, made by pharma behemoth Merck. Tyson made the move based on “animal well-being” concerns, it told its cattle suppliers in a letter, adding that “there have been recent instances of cattle delivered for processing that have difficulty walking or are unable to move.” According to the Wall Street journal, Zilmax (active ingredient: zilpaterol hydrochloride) and similar growth promotors are banned in the European Union, China, and Russia.

The news sent shock waves through the beef industry. Merck denied any problems with its drug but announced it would temporarily suspend sales of Zilmax in the United States and Canada pending a “scientific audit” of the product, which generated $159 million in US and Canadian sales in 2012, Merck added. Soon after, Tyson rivals JBS, Cargill, and National Beefpacking announced that they, too, would stop accepting Zilmax-treated cattle for slaughter, pending Merck’s review.

Together, Tyson, JBS, Cargill, and National slaughter and pack more than 80 percent of the beef cows raised in the United States, according to University of Missouri researcher Mary Hendrickson (PDF). If they stick to their refusal to buy cows treated with the drug, it’s hard to see how Zilmax has a future on America’s teeming cattle feedlots. Is the US beef industry turning away from the practice of turning to drugs to fatten its cattle?

Not so fast. Rather than wean themselves from growth promoters, the companies that produce cows to supply the likes of Tyson and JBS are instead shifting rapidly to a rival beta-agonist, this one from pharma giant Eli Lilly, called Optaflexx. The suspension of Zilmax sales has caused such a “surge in demand” for rival Optaflexx that “Lilly is telling some new customers it cannot immediately supply them,” Reuters reported.

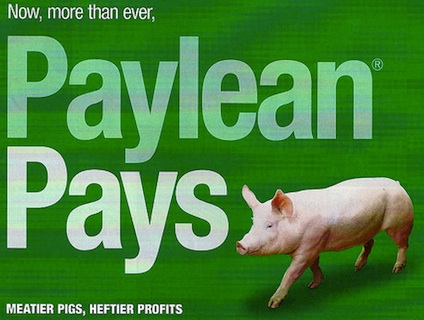

Close readers of this blog will recognize the active ingredient in Optaflexx: It’s ractopamine, a drug wildly popular on factory-scale hog farms, and also highly controversial, as the excellent food safety reporter Helena Bottemiller showed in a 2012 article. Ractopamine “mimics stress hormones, making the heart beat faster and relaxing blood vessels,” Bottemiller reported. She added:

Since the drug was introduced [in 1999], more than 160,000 pigs taking ractopamine were reported to have suffered adverse effects, as of March 2011, according to a review of FDA records. The drug has triggered more adverse reports in pigs than any other animal drug on the market. Pigs suffered from hyperactivity, trembling, broken limbs, inability to walk and death, according to FDA reports released under a Freedom of Information Act request. The FDA, however, says such data do not establish that the drug caused these effects.

So why are the companies that fatten cattle for the big beef processors—known as “cattle feeders”—so intent on using controversial drugs like Zilmax and Optaflexx? The answer lies in meat industry’s brutal economics. Cattle feeders are stuck between high recent prices for corn and soy feed—pushed up by last year’s severe drought and also by high demand for corn from the ethanol industry—and the low prices offered to them for beef cows by the likes of Tyson and JBS.

According to a recent report in Reuters, citing figures from the Denver-based Livestock Marketing Information Center, cattle feedlots lost on average about $82 per head of cattle sold to the meatpacking industry, “the 27th straight month of losses.” Using growth promoters like Zilmax and Optaflexx, which cause cattle to put on muscle rapidly without increasing their feed needs, “mitigated those losses an estimated $30 or $40 per head.”

Apparently, Zilmax works a bit better than Optaflexx—both in terms of fattening cattle and helping feedlot operators trim losses. Quoting a feedlot operator, Reuters reported that Zilmax costs roughly $20 per head while generating between $15 to $30 worth additional meat for market, while Optaflexx costs $8 to $10 but brings in just $10 to $12 in extra revenue.

So why are the big meatpackers banning Zilmax when it hurts the bottom lines of their already struggling suppliers?

Frankly, Tyson’s claim that it’s all about “animal well-being” strains credulity. Tyson is also a massive pork producer, and it has shaken off years of pressure to abandon the practice of housing pregnant pigs in tiny crates, even as rivals Smithfield, Cargill, and Hormel have taken steps to do just that. In terms of stress-causing feed additives, Smithfield recently declared it would soon ensure that half of its pork comes from pigs not treated with ractopamine, explicitly with an eye toward exporting pork to China, which bans ractopamine-treated pork. (Not long after, a Chinese meat company returned the favor by buying Smithfield, in a deal pending approval by US trade authorities.) Tyson, too, has started producing some pork without ractopamine, also with an eye toward foreign markets.

Might a similar desire be motivating Tyson’s move on Zilmax? NPR has speculated as much. Americans’ appetite for beef has been waning for decades—we now eat an average of about 60 pounds per person annually, versus about 80 pounds in the late 1970s.* That means that the big meatpackers have had to look to exports to eke out profit growth. And the China market looms as an attractive prize—according to a recent joint FAO/OECD report (see page 95), China’s beef imports will likely nearly double over the next decade. With US beef banned there, other countries—Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, and Uruguay—have that lucrative market sewn up.

Is Tyson angling for a piece of the China pie? Of course, in order to produce the kind of additive-free beef desired by big importers like China and Russia, Tyson would have to ban not just Zilmax but also ractopamine-laced Optaflexx, too. I can’t help but wonder if the Zilmax ban isn’t phase one of an export strategy that would entail banning Optaflexx next. That would mean even more relentless pressure on its suppliers. Until Tyson and its peers agree to pay feedlots more for beef cows, the industry will remain effectively addicted to growth-promoting drugs—or in financially difficult withdrawal from them.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly stated the amount of beef consumed now and in the 1970s. The sentence has since been fixed.