One of two abandoned buildings that remain from the old Fulton Fish Market. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/manyhighways/2774083428/">Many Highways</a>/Flickr

For nearly 200 years in Lower Manhattan, Fulton Fish Market served as a bustling, aromatic, and, late in its tenure, reportedly Mob-connected wholesaler linking the city’s restaurants and food retailers to the eastern seaboard’s fisheries. Long before its emergence as a covered market in the early 19th century, the site had been a place where people gathered to trade fish and other foodstuffs. The market’s vendors moved to the Bronx in 2005, leaving behind two historic remnants, known as the Tin Building and the New Market Building.

Now there’s a battle afoot over what should become of those two abandoned city-owned edifices, which sit on the East River just south of Brooklyn Bridge at the edge of South Street Seaport, a once-vibrant commercial port that was transformed in the 1980s into a dismal mall. On the one side, there’s the folks at New Amsterdam Market, who want to transform the two-building site into a grand food market, in the style of Seattle’s Pike Place or Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal. (New Amsterdam Market hosts weekly markets outside of the old Fulton buildings, with the hope of one day running a permanent, publicly owned indoor market at the site. ) On the other, there’s Howard Hughes Corp. (a real estate holding firm spun off from a company originally started by the famous magnate Howard Hughes), which is in negotiations with the city to redevelop it and is already in the process of redeveloping South Street Seaport. The company’s plans for the old fish-market sites remain murky, but aren’t likely to include a vast, city-owned food emporium.

Like all land-use issues in New York City, this one is complicated. But I agree with New Amsterdam: The two historic waterfront market buildings are a glittering municipal asset, and the city should move quickly to re-establish them as a place where people assemble to buy and sell food. Municipal food markets might seem like relics from a lost pre-supermarket past, but they’re actually quite durable—and they’re surging in popularity as Americans are thinking more critically about how and what they eat. Detroit is a city perennially down on its luck, but its Eastern Market, which dates to 1891, still thrives. Same with Cleveland’s 100-year-old West Side Market, Seattle’s Pike (1907), and Philly’s Reading (1893). Even ultra-modern Los Angeles, land of highways and sprawl, has supported its downtown Grand Central Market since 1917 (and it’s now getting a makeover).

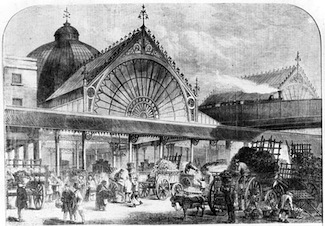

Then there’s Barcelona’s La Boqueria, London’s Borough Market, and Mexico City’s La Merced, all occupying land on which food has been traded for hundreds of years, all now occupying structures built in the 19th century, and all bustling today, drawing locals and tourists alike. Meanwhile, what Zola called the “belly of Paris,” Les Halles Market, lives on only in remnants. The 1970s-era decision to obliterate it, making way for a mall, will haunt the city forever.

In their odd status as both old-fashioned and anything-but-obsolete, city markets resemble trains and the venerable buildings where people alight to catch them. As the late historian Tony Judt put it in a gorgeous 2011 essay, trains “are perennially modern—even if they slip from sight for a while.” They already represented “modern life incarnate by the 1840s — hence their appeal to ‘modernist’ painters,” he writes. And yet, “the Japanese Shinkansen and the French TGV are the very icons of technological wizardry and high comfort at 190 mph today.”

Judt also noted the magnificent durability of old train stations—when they haven’t been sacrificed to the wrecking ball like Manhattan’s original Penn Station. Mentioning Paris’ Gare de l’Est (1852), London’s Paddington Station (1854), Bombay’s Victoria Station (1887), and Zurich’s Hauptbahnhof (1893), Judt notes that “they work in ways fundamentally identical to the way they worked when they were first built. This is a testament to the quality of their design and construction, of course; but it also speaks to their perennial contemporaneity. They do not become ‘out of date.’ “

Judt’s description captures both the romance and enduring utility of city markets. As the explosive growth of farmers markets—up more than fourfold since 1994—shows, more and more Americans want to eat food that’s an expression of their surrounding landscape, processed, prepared, and vended when possible by people around them. The popularity of farmers markets also suggests that consumers want to buy food in interesting spaces that put them face-to-face with independent vendors. A covered, year-round market, teeming with purveyors and producers of regionally sourced veggies, cheese, meat, and pickled foods, would fill that role even better than Manhattan’s uncovered, four-days-per-week Union Square Greenmarket can.

And such a food market would leverage and showcase the city’s food-manufacturing revival, which the New York City Economic Development Corp. calls a “key component of the City’s economy and one of the City’s industrial success stories.” As of 2011, New York housed 1,000 food manufacturing businesses, employing 14,000 people and generating $2.9 billion in sales, NYCEDC claims. (In a 2010 post, I wrote about the economic possibilities and limits of the city’s budding food-artisan movement.)

On Wednesday, a small breakthrough in the fight over Fulton emerged. Under pressure from supporters of the Fulton market idea, who had swarmed a hearing on the South Street Seaport redevelopment a week before, the New York City Council announced it had reached deal with the Howard Hughes Corp. on the redevelopment of one of the old Fulton market’s historic buildings, the Tin Building. According to a Council press release, reprinted here, Howard Hughes agreed that “any proposal for a Mixed Use Project at the Tin Building must include a food market occupying at least 10,000 square feet of floor space that includes locally and regionally sourced food items that are sold by multiple vendors and is open to the public seven days a week.”

That’s a start, but it’s not adequate. Robert LaValva, president of New Amsterdam Market, told me that the two remaining market buildings occupy a combined 50,000 square feet—versus 180,000 square feet for London’s Borough Market, he added. Cutting down the remaining Fulton footprint to a fifth of its potential total is a cramped vision for what should be a grand market. LaValva vowed to me that the fight to restore the full market will continue. I hope it does.