A worker cleans up oily waste on Elmer’s Island, Louisiana, on May 21, 2010: Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Patrick Kelley, US Coast Guard, via Flickr

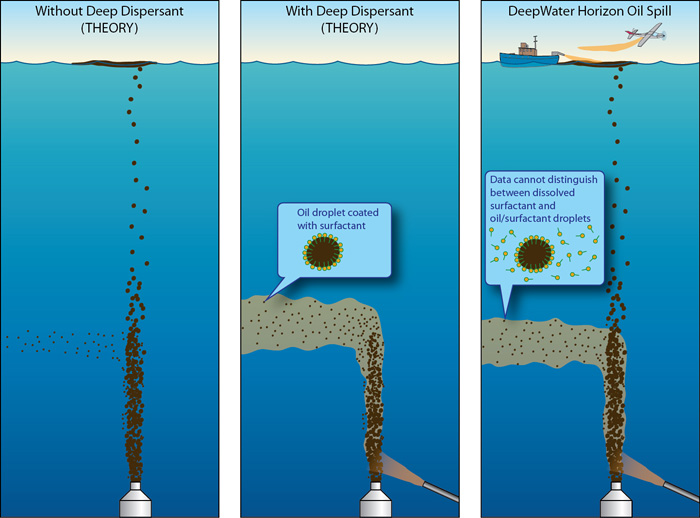

In an attempt to deal with the 206 million gallons of light crude oil erupting from the Deepwater Horizon blowout in 2010, BP unleashed about 2.6 million gallons of Corexit dispersants (Corexit 9500A and Corexit EC9527) in surface waters and at the wellhead on the sea floor. From the beginning the wisdom of that decision was questioned. I wrote extensively about those concerns in “BP’s Deep Secrets.”

In the short term the dispersed oil made BP’s catastrophe look like less of a catastrophe since less oil made it to shore. But what about the long term?

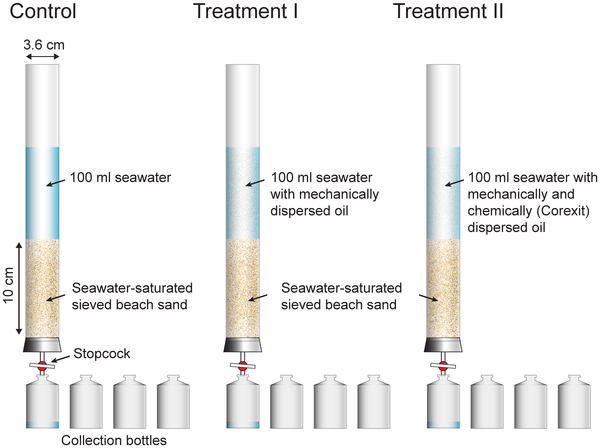

In a new paper in PLOS ONE, researchers took a closer look. They examined the effects of oil dispersed mechanically (sonication), oil dispersed by Corexit 9500A, and just plain seawater (the control). They used laboratory-column experiments to simulate the movement of dispersed and nondispersed oil through sandy beach sediments.

Clean seawater, crude oil dispersed by sonication, or crude oil dispersed by Corexit and sonication were flushed through the sand columns by gravity. The effluent of the columns was collected as a time series in four vials each. PLOS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050549.g001

Clean seawater, crude oil dispersed by sonication, or crude oil dispersed by Corexit and sonication were flushed through the sand columns by gravity. The effluent of the columns was collected as a time series in four vials each. PLOS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050549.g001

Their findings: Corexit 9500A allows crude oil components to penetrate faster and deeper into permeable saturated sands where the absence of oxygen may slow degradation and extend the lifespan of potentially harmful polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a.k.a. organic pollutants—a.k.a. persistently abominable hork—in the marine environment.

Furthermore, the authors warn, dispersants used in nearshore oil spills might penetrate deeply enough into saturated sands to threaten groundwater supplies. (Did anyone look at this in the BP settlement?)

How does dispersant change oil’s behavior in a beach? The authors write:

The causes of the reduced PAH retention after dispersant application has several reasons: 1) the dispersant transforms the oil containing the PAHs into small micelles that can penetrate through the interstitial space of the sand. 2) the coating of the oil particles produced by the dispersant reduces the sorption to the sand grains, 3) saline conditions enhance the adsorption of dispersant to sand surfaces, thereby reducing the sorption of oil to the grains.

In other words, repeated flushing by waves washing up a contaminated beach may pump PAHs deep into the sediment when dispersant is present. Natural dispersants—those produced by oil-degrading bacteria—may support this effect when oil is present in the sand for longer time periods.

Furthermore the continuous flushing by waves on an oil-contaminated beach may result in the release of PAHs from the sand back to the water. And after PAHs are released from the sediment, UV light can increase their degradation but also increase their toxicity to marine life by up to eightfold.

As for what effects those long-lived PAHs have released back into the water, the authors cite recent research findings:

- Increased mortality in planktonic copepods exposed to dispersants with stronger effects on small-sized species.

- In early life stages of Atlantic herring dispersed oil dramatically impaired fertilization success.

- Grey mullet exposed to chemically dispersed oil showed both a higher bioconcentration of PAHs and a higher mortality than fish exposed to either the water-soluble fraction of oil or the mechanically dispersed oil.

Workers from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the US Fish and Wildlife Service prepare to net an oiled pelican in Barataria Bay, June 5, 2010: Deepwater Horizon Response via Flickr

Workers from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the US Fish and Wildlife Service prepare to net an oiled pelican in Barataria Bay, June 5, 2010: Deepwater Horizon Response via Flickr

The open access paper:

- Alissa Zuijdgeest and Markus Huettel. Dispersants as Used in Response to the MC252-Spill Lead to Higher Mobility of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Oil-Contaminated Gulf of Mexico Sand. PLOS ONE (2012). DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0050549