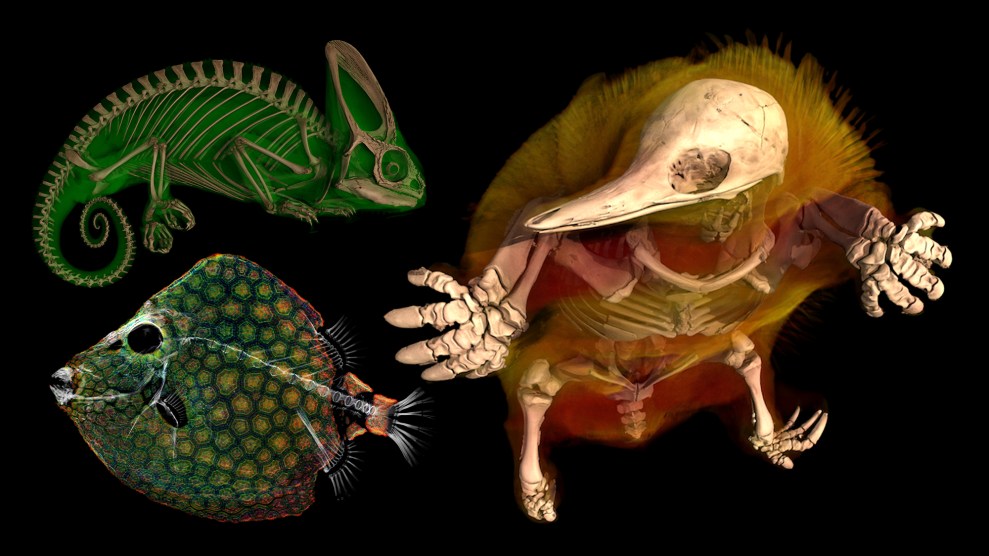

Cocioba helped design a morning glory flower for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.Klaus-Dietmar Gabbert/dpa/Zuma

This story was originally published by Wired and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Sebastian Cocioba’s clapboard house on Long Island doesn’t look much like a cutting-edge plant biology lab. Then you step inside and peer down the hallway to see a small nook with just enough standing room for a single scientist. The workshop is stuffed with equipment Cocioba scored on eBay or cobbled together himself with a little engineering knowledge. This is where the 34-year-old attempts to use gene editing to create new kinds of flowers more beautiful and sweeter smelling than any that currently exist. And it’s also where he hopes to blow the closed-off world of genetic engineering wide open.

Cocioba’s fascination with plants started in childhood when he was enthralled by the intricate inner structure of a fallen maple leaf. During high school, he noticed a dumpster full of orchids outside a Home Depot store. He took the plants—his mother’s favorites—and coaxed them back into bloom with the help of some growth hormone paste bought online. Soon he was selling the plants back to the store. “I had this racket going where I was taking their trash, reflowering it, and selling it back to them,” he says.

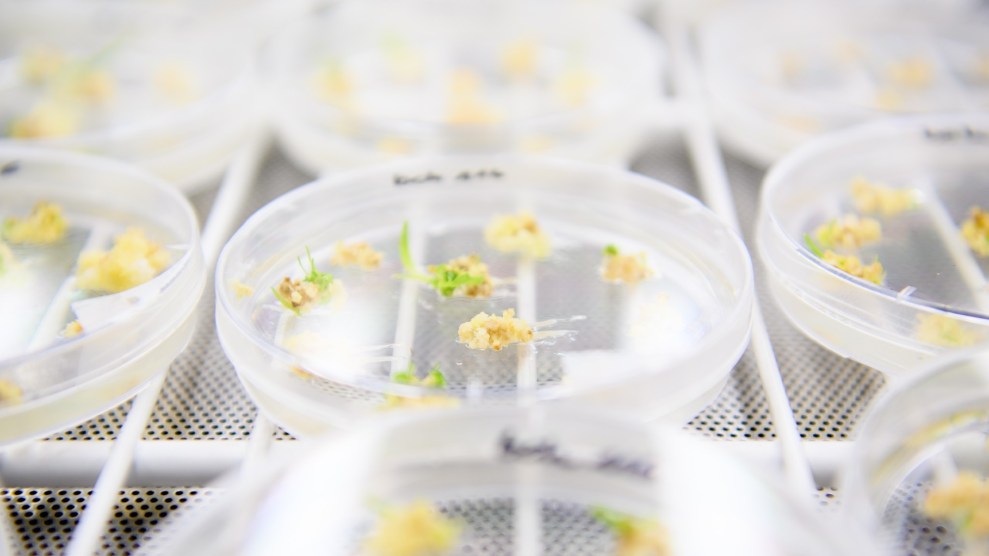

The money he earned doing that was enough to put Cocioba through the first couple of years of a biology degree at Stony Brook University. He completed a stint with a neglected plant biology group that taught him to experiment on a shoestring budget. “We were using toothpicks and yogurt cups to do petri dishes and all of that,” he says. But financial difficulties meant he had to drop out. Before he left, one of his labmates handed him a tube of agrobacterium—a microbe commonly used to engineer new attributes into plants.

Cocioba set about transforming his hallway nook into a makeshift lab. He realized that he could buy cheap equipment in fire sales from labs that were shutting down and sell them on for a markup. “That gave me a little bit of an income stream,” he says. Later he learned to 3D-print relatively simple pieces of equipment that are sold at extreme markups. A light box used to visualize DNA, for example, could be cobbled together with some cheap LEDs, a piece of glass, and a light switch. The same device would retail to laboratories for hundreds of dollars. “I have this 3D printer, and it’s been the most enabling technology for me,” Cocioba says.

All of this tinkering was in aid of Cocioba’s main mission: to become a flower designer. “Imagine being the Willy Wonka of flowers, without the sexism, racism, and strange little slaves,” he says. In the US, genetically modified flower work is covered by the lowest biosafety rating, so it doesn’t subject Cocioba or his lab to onerous regulations. Doing gene-editing as an amateur in the UK or EU would be impossible, he says.

“Imagine being the Willy Wonka of flowers, without the sexism, racism, and strange little slaves.”

Cocioba set himself up as a self-described “pipette for hire”—working for startups to develop scientific proof-of-concepts. In the run-up to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the plant biologist Elizabeth Hénaff asked Cocioba for help with a project she was working on: designing a morning glory flower with the Games’ blue-and-white checkerboard pattern. It just so happened that a checkerboard flower already existed in nature—the snake’s head fritillary. Cocioba wondered if he could import some of the genes from that plant into a morning glory. Unfortunately, it turned out that the snake’s head fritillary had one of the largest genomes on the planet and had never been sequenced. With the Olympics looming, the project fell apart. “It ended in heartbreak, of course, because we couldn’t execute on it.”

As Cocioba moved deeper into the world of synthetic biology, he started to shift his focus slightly—away from just creating new kinds of plants and toward opening up the tools of science itself. Now he documents his experiments on an online notebook that’s free for anyone to use. He also started selling some of the plasmids—small circles of plant DNA—that he uses to transform flowers.

“We’re at the golden age of biotech for sure,” he says. Access is greater, and the research community is more open than ever before. Cocioba is trying to recreate something like the 19th-century boom of amateur plant breeders—where hobbyist scientists shared their materials partly just for the thrill of creating new plant varieties. “You don’t have to be a professional scientist to do science,” Cocioba says.

Alongside this work, Cocioba is also a project scientist at the California-based startup Senseory Plants. The company wants to engineer indoor plants to produce unique scents—a biological alternative to candles or incense sticks. One idea he’s playing with is engineering a plant to smell like old books, olfactorily transforming a room into an ancient library. The startup is exploring a whole smellscape of evocative scents, Cocioba says, in part designed in his home laboratory. “I really, really, love what they’re doing.”