Debris covers the River Arts District in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene flooding in Asheville, North Carolina. Mario Tama/Getty

Three weeks after Hurricane Helene hit western North Carolina, Brandi Hand, a marketing and communications writer and based just outside of Asheville, offered some practical advice to her community: In a Facebook post that’s since been shared thousands of times, she wrote, “Find ways to laugh.” “Be gentle.” And, “Get ready for the rest of the world to forget about us,” among other tips.

Asheville was supposed to be a climate haven.

Hand, after all, had been through this before. She grew up in Louisiana. In August 2005, she and her husband, Tom, lost their New Orleans home and everything they owned in Hurricane Katrina, a storm that killed nearly 1,400 people and displaced around a million others. She watched their once-vibrant neighborhood of Gentilly wither. Seeking a fresh start—and safety from hurricanes—they moved to the mountains of Western North Carolina in 2008. If such a thing existed, Asheville was supposed to be a climate haven.

Then Helene came, and left what at least one official called “biblical” damage in its wake. More than 200 people died. An estimated 126,000 homes have been destroyed or damaged in North Carolina alone. Luckily, this time, Hand’s home was spared, but as she wrote on Facebook, “[E]verything else is exactly the same—the feelings of helplessness, anxiety, grief, confusion, anger.” On top of it all, last month, Hand’s grandfather died.

Below, in her own words, Hand shares what it’s like to live through not just one of the most deadly hurricanes ever to hit the United States, but two. While media reports typically capture the big-picture toll of disasters like Katrina and Helene, she said, they often miss many of life’s smaller tragedies: the loss of favorite restaurants, shops, parks, and libraries. The loss of normalcy. As she told me when I spoke with her earlier this month, as the rest of the world moves on, she’s worried about what’s next for North Carolina.

Her story has been edited and condensed for clarity.

As a little girl, my grandfather taught me about how dangerous New Orleans would be if a major hurricane ever hit. He would show me a bowl—New Orleans is in the middle of the bowl, and the edges of the bowl are the surrounding levees. If those levees break, all of the water comes into New Orleans, and it just sits there. And so he always taught me, you have to leave. You have to get out. So for me, it was never a question.

When we evacuated, we had our two vehicles. Tom took our two dogs and I took the four cats in their carriers, and we took about four days’ worth of clothes and dog food and cat food. That’s what we evacuated with.

“Lake Pontchartrain was in my house, basically.”

It was a good month before we were able to go back to see our house. Like most homes in New Orleans, it was raised three feet off of the ground, but there was 10 feet of water in my neighborhood, so we ended up having seven feet of water in our home. Lake Pontchartrain was in my house, basically. And it takes a long time for that water to go away.

We could see where the water had sat for weeks. It was just disgusting—just sludge. And by the time we had gotten there, there was already mold. You could smell it, just mold everywhere. We even had mold growing on the shingles of our house, which I didn’t even know was possible.

We couldn’t save our plates and bowls and things, because the water gets into those porous materials, and you can’t ever get it out. Our clothes—you had to break them to put them into bags because they dried stiff like concrete. We had to get rid of everything. We [eventually] sold our house to a contractor, and moved into the house next door.

It’s a very wearing and taxing thing to live in a place that doesn’t work anymore. Everybody is living in a broken city. It’s not like when something horrific happens to a particular family, like their house burns down, and your community can gather around them and support them and make sure they’re taken care of. This happened to an entire city of people. So everybody isn’t at their best. Everybody is suffering.

[One day,] I was napping, and I awoke to the sound of gunshots that sounded really close. I found out later on that somebody had been murdered on my block. That was the last straw for me. My husband came home from work later that evening, and I’d started boxing things up. I was like, “We’re moving.”

January 1, 2008, we arrived in Candler, North Carolina, just outside of Asheville. It was a very practical decision—we thought. I wanted to live somewhere where this would never happen again. We got a map out and we looked at all these different places in the United States that we considered safe. We ruled out entire areas because of hurricanes and earthquakes and that sort of thing. And Asheville kept rising to the top.

“I wanted to live somewhere where this would never happen again.”

We do know some people who lost everything, but Candler was one of the more fortunate areas. We live right on Hominy Creek, and it’s normally about six to 12 inches deep. It became a raging river overnight. I have videos of storage containers, entire trees, and a van going by. The creek bed will never be the same again.

We have thousands and thousands of dollars in damage to our land that we can’t afford to fix. We were going to create an orchard and a garden, things that I had been dreaming about for years and had been saving up for. We have massive cracks in the land, and according to the geoengineer who came out and looked at it, a lot of it is going to fall into the river.

We didn’t have flood insurance. Because why would we? We’re at high elevations here. That’s my big worry for just about everybody in western North Carolina. Katrina didn’t completely ruin us financially because we had flood insurance. For those people who have lost their homes [in Helene], are they going to be expected to pay a mortgage for the next 20 to 30 years on a home that was completely destroyed?

The Friday that Helene hit here, we had already planned to leave to go to Louisiana so that I could say goodbye to my grandfather before he died. He was more like a dad to me than he was a grandparent. And his body was filling up with fluid.

I kept saying to Tom, “We’ve got to go.” And he kept saying, “It’s not safe yet to go. We have to wait for this wind to die down, we have to wait for this rain to die down.” And I was feeling okay about it until—I call it my hurricane instinct, kicked in. It was around one o’clock on Friday, and I said, “If we don’t leave in the next 10 minutes, I’m never going to see my grandfather again.” And so we did. We just got in the car and left.

My instinct was right. Had we left even 45 minutes later—they had started closing down roads. There were landslides. Everything was flooded. So we just got very lucky that we left when we did. I got to see him.

That’s another thing people don’t think about in these disasters. Babies are being born, people are dying. People are getting sick. People are going through divorce. Whatever it is, life still goes on.

I felt a little crazy. I didn’t know where to put my grief. When I was with my grandfather, when I was in the room with him, I could just be with him. But later, my mind would just start—I couldn’t land on any one thing. That’s why I’m still struggling right now. I still haven’t fully grieved. I still haven’t fully dealt with what has happened to my community here.

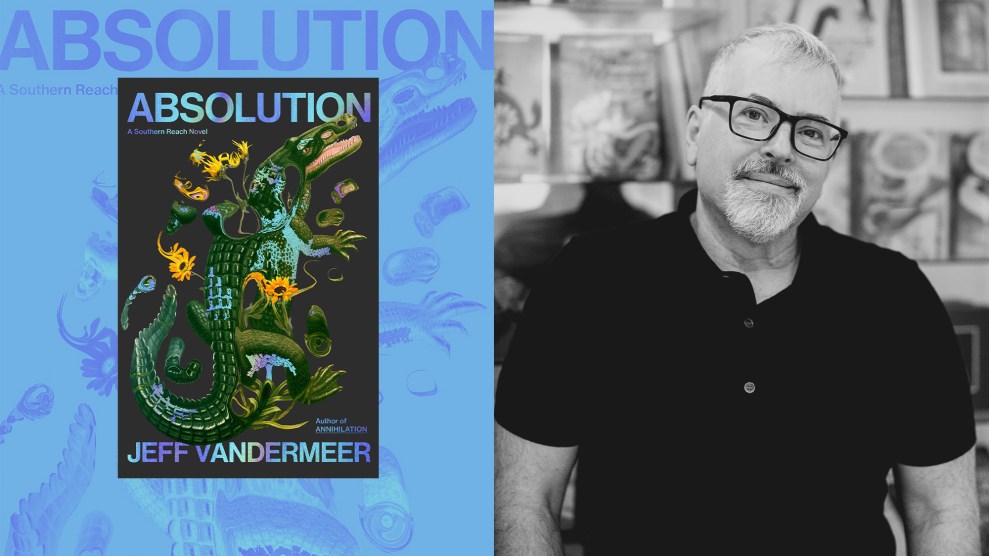

You can never prepare yourself for what it’s like to lose things that you count on. Entire parks are just gone. In Asheville, our River Arts District where a lot of our artists do and sell their work, that was just absolutely annihilated by the water.

You take for granted that you’re going to see your older neighbor walk around the block every day, and you can almost set your watch to it. And then that neighbor is gone forever, and you have no idea if he’s dead or alive. That was New Orleans.

You depend on your library, or your favorite local little noodle restaurant. They’re gonna be there—and then they’re just gone. It’s really difficult to get your head around that.

You have the big news, like the number of deaths. But what people don’t know about is the small stuff. The very ground underneath your feet is not solid in the same way again, for the rest of your life.

“You have the big news, like the number of deaths. But what people don’t know about is the small stuff.”

Our news cycle is so fast that if you don’t hear about something, when you’re on the outside, you assume that everything is okay. That’s just not the case. Winter is coming to North Carolina and people are living in tents. The water is not safe. You cannot drink it. Some people can’t even bathe in it because it affects their skin so negatively. [Editor’s note: After Hand spoke with Mother Jones, seven weeks after Helene, Asheville announced its tap water is now drinkable.]

This isn’t even close to over for this area. And knowing what I know, we’re in for a lot more heartache. People are going to leave because they have to. Businesses are going to leave because they have to.

And if the world can forget about the people of New Orleans starving to death in the streets—before going through Katrina, I didn’t think that something like that could happen in this country. The whole world saw it, and then they forgot about us. So I know that that’s going to happen again in this area.

I’m usually a very optimistic person, but I’m not sure I’m there yet. I just have to put my faith in the people of this area and their ability to take care of one another. I think we’re good at that.