Cruz Salucio, host of Radio Conciencia, third from left, alongside Coalition of Immokalee Workers membersCourtesy Coalition of Immokalee Workers

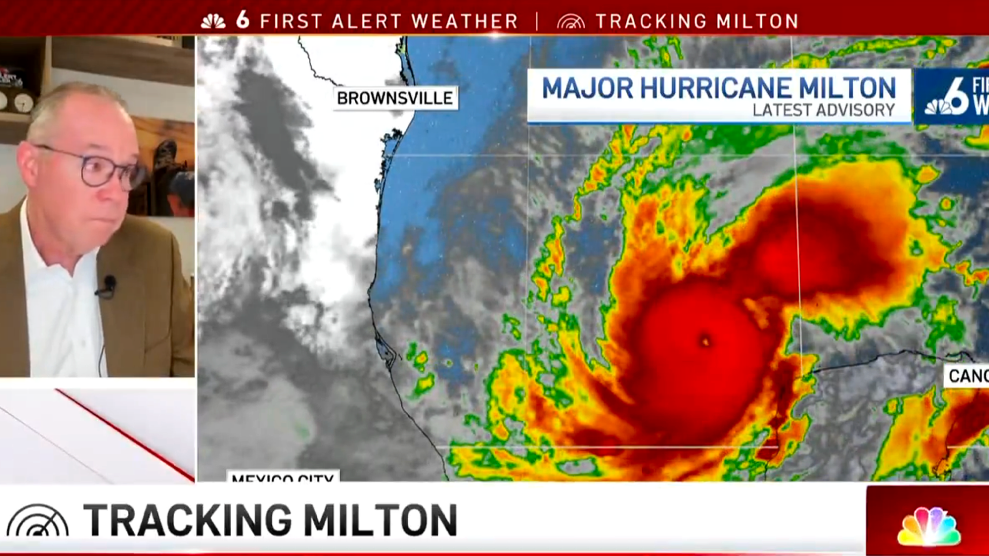

When Hurricane Milton rapidly intensified last week, exploding into a Category 5 storm, large parts of Florida were bracing for disaster. For Cruz Salucio, Milton wouldn’t be the first, or the worst, hurricane he’d endured. But it sparked anxiety all the same.

Salucio works for the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ local radio station, Radio Conciencia. The organization primarily serves farmworkers in Southern Florida, but its various programs have a presence in 15 states around the country.

When hurricanes like Milton, Idalia, and Ian have approached, Salucio and other radio DJs were often the most direct source of reliable, fact-checked information for the region’s Spanish- and Mayan-speaking migrant workers. Climate change is intensifying these types of storms and in the process straining resources, endangering millions of people. For workers with few resources, hurricanes can be isolating and devastating events. But Radio Conciencia tries to fill the gaps as much as possible.

People at the station often answer questions about shelters and evacuation routes. Amid the deluge of information and misinformation, Radio Conciencia has become a trusted resource for many. It helps that, when there’s not a crisis, the station plays traditional genres of music like Banda, a regional Mexican style originally influenced by polka, or marimba-centric music popular in Guatemala. It also supplements the music with messages about workers’ rights and safety, filling a vital knowledge gap.

Salucio spoke with me, via translation, about what it feels like to provide a lifesaving resource in trying times. His story has been edited and condensed for clarity:

I remember when I first came to Immokalee trying to find a radio station to listen to. Scrolling through the dial, I came across the music that was playing on Radio Conciencia. It was a Sunday, and I remember hearing marimba, which is a traditional Guatemalan instrument, and also hearing the radio host speaking in Q’anjob’al, an Indigenous language from Guatemala. It was so striking to me at that moment to hear not only the music, but also my first language, and to have that direct connection to where I had just come from.

From there, I got really involved. I came to Radio Conciencia because it’s a community radio station. You yourself can get involved and learn how to speak on radio and manage it technologically.

When I was working in the fields back in the 2000s, you’ll often have this experience where the bosses on a particular farm want to get as much harvested as possible, quickly, before the hurricane arrives. They’ll wait till the very last minute to let people leave. Having that experience myself—that’s really what drives me.

When I’m sitting and broadcasting from the radio during these moments of crisis, where I know that members of the community, their lives and their wellbeing are in danger, it feels incredibly important to make sure they know that. I feel a profound commitment to the radio and its purpose, especially in those moments, to the point that, especially now that I have a family, there’s that kind of balancing act of being home with family and sometimes needing to get back to the office to record some last-minute audio tracks or be live on the radio.

Our goal is always to ensure that people have the information they need when they need it, that they know how to prepare for these types of crises, and, especially during a hurricane, to know where they can go to shelter.

Days ahead of a hurricane’s arrival, we will work on original announcements that we can program with important information about what to do, how to prepare, how to stay safe during and after. We’ll record and program those announcements to play to everyone periodically, so even if there’s not someone live in the station, those messages are still getting out there. And of course the other limitation is if power goes out. That does affect the radio but we try to be as prepared as possible for those eventualities.

The good news is that our radio station and community center are in quite a safe building. Even during this most recent hurricane [Milton], some of our staff and radio DJs actually sheltered and stayed here, so they were able to continue broadcasting. We’re safer here than they might have been in their homes.

The main thing we hear from listeners during these times is just deep gratitude. A lot of people in the community, by phone and on social media, reach out to say thank you for having a place they can go to in their language that has good and reliable information, that isn’t creating panic. They will call us and say, “I live in a really crappy trailer and I don’t feel safe—where can I go? Where are the shelters?”

These storms not only impact the community but will wipe out entire agricultural fields. So they’ll call and say, “Have you heard anything? Do you know what’s happened in the tomato fields?”

“I’ve gone to the public shelters as well…It’s actually kind of a beautiful scene sometimes, and a good place to connect with the community and chat with people and see how everyone’s doing.”

Sometimes we’ll give them the terrible news that the entire fields got wiped out, which means no work. It always depends on the nature of the storm. For this particular storm, we could tell, basically in the final hours before the storm, that it wasn’t going to hit as hard here. So I sheltered at home with my family. The worst of it did not come inland to Immokalee.

During other hurricanes, when I’ve lived in trailers and other insecure housing, I’ve gone to the public shelters not only to be safe myself, but it’s actually kind of a beautiful scene sometimes, and a good place to connect with the community and chat with people and see how everyone’s doing.

The reality for so many farmworkers is, especially when you’re living in trailers and really poor housing, you have so little and you are afraid of losing the little you do have of your belongings. Some people try to ride it out in their housing. Or they’re afraid that if they leave and then come back, what are they going to come back to? It might be nothing. Ideally, people will go when they need to, find a shelter to be safe if it’s going to be an extreme storm—even with that fear of losing everything they have.

Correction, Oct. 18, 2024: This story was corrected to accurately reflect the number of states where the Coalition of Immokalee workers has programs.