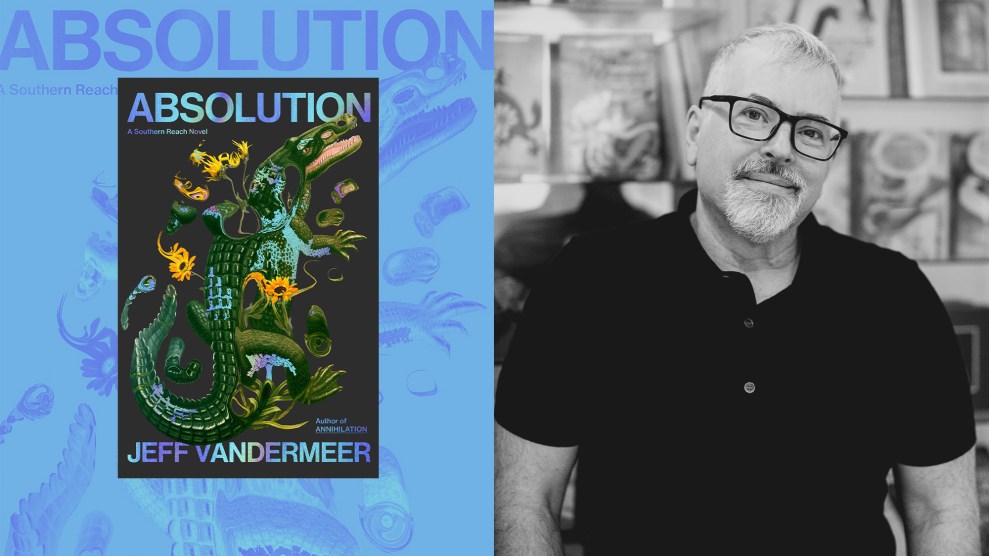

Author Jeff VanderMeer's new novel is called "Absolution."Mother Jones; Azhar Khan; MCD/FSG

Jeff VanderMeer insists that he does not predict the future. Yet mere weeks before his new novel, Absolution, hit shelves, Hurricane Helene tore through the part of Florida where he lives, sharing an uncanny likeness to the fictional hurricane in his book. Of course, there’s a difference between art and reality. The through line between the storms is the climate crisis that inspired VanderMeer to write the trilogy of books that made him a household name a decade ago.

Absolution is the latest and last installment in the lush, eerie series covering an unknown biological phenomenon known as Area X, located in VanderMeer’s home state of Florida in the real place known as the Forgotten Coast. The original trio of books covers the area and its tendency to affect living creatures and create bizarre refractions of life within its confines. The series, called the Southern Reach trilogy, garnered enormous praise, a legion of fans, and a movie adaptation. For the record, VanderMeer told me he found Hollywood “frustrating” because “they stripped out all the environmental stuff.” But he did enjoy the movie’s surreal ending.

“We get displaced. We have to be resilient. We have to form a new narrative.”

A decade later, Absolution marks the conclusion of a weird and wonderful journey involving an assortment of biological abnormalities and government secrets. In the meantime, it seems as if the unusual world that VanderMeer wrote about and the one that we live in today are growing closer and closer. Our warmer world is not just more volatile in terms of natural disasters, like Helene and Milton, but it is also becoming a large-scale petri-dish for new diseases, the type of biological mixing and matching that VanderMeer’s books are known for—albeit on a much smaller scale.

In VanderMeer’s fiction, the mirror world of Area X produced strange, haunting results like a character’s transformation into a whale-like creature covered in eyes, or a murderous bear with a human voice. But for VanderMeer, climate change is the scariest thing of all.

I spoke with him just as he was returning to his home in Tallahassee after evacuating from Hurricane Helene. This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

What is it like being a climate and science fiction writer right now?

I guess it feels like kind of a privilege to be able to talk about this stuff, that the novels have reached enough readers and had enough of an impact that anyone cares what I have to say.

It’s also true that I’m right now in Florida, at the epicenter of a lot of extreme weather events. And so that creates a weird echoing effect. For example, I was fleeing Hurricane Helene up to Greenville, South Carolina, unsure if that was even the right thing to do. And then also asked by the New York Times to write a piece about fleeing the hurricane. So there’s all this real-world consequence.

You’re getting me at the end of fleeing a hurricane, writing about it, coming back to Tallahassee, seeing the consequences of extreme weather because of warming waters because of climate crisis, and feeling both thankful that I can kind of capture a feeling people have here about these events and write about it, but also kind of caught up in it as well.

That sounds pretty jarring.

You can get in loops too, where you don’t really adapt to the situation and you’re just doing the same talking points which, relevant to your question, is something I worry about. You know, where [people on the internet] were saying, “Well, why did people even build in Asheville?” it was this weird disconnect. And it’s like, “Well, because they didn’t expect there’d be these mega-storms that would still have a huge effect, hundreds of miles inland.”

People in the aftermath of destruction seem to want to try to form their own narratives about what’s happening, and I’m sure you are someone who see this clearly, being in the epicenter, but also being someone who works in fiction.

It’s definitely something that I write about in my fiction: the idea of character agency in the face of systemic or system-wide events, whether they’re human systems or systems in the natural world. Especially in Western fiction, we have this idea of rugged individualism, right? And by the end of the narrative, things will have gone back to normal, because something’s been solved.

That’s not really what happens in the real world. We get displaced. We have to be resilient. We have to form a new narrative. We’re not always the same person we were before, you know, especially with regard to the climate crisis. And so I try to capture that. There’s a hurricane in Absolution that comes up suddenly in the middle of all these other events. And I really wanted to capture how a hurricane these days can seem like an uncanny event, even to those of us who are familiar with them.

“People think the climate crisis is on the horizon…But more and more, we’re all being affected by it.”

Helene, to be candid, scared the crap out of me when I saw it coming to Tallahassee with 150 mile per hour winds. A lot of people decamped from Tallahassee up into North Carolina, and then were completely trapped. People think the climate crisis is on the horizon, and if they think that it’s because they haven’t been affected by it yet. But more and more, we’re all being affected by it.

In this book, Absolution, and in all the books, there are these in-group, out-group dynamics, and I’m just wondering, why is that something that you’re really interested in exploring narratively?

I’m trying to explore the psychological reality of being in these situations. I’m not trying to extrapolate, I’m not trying to predict. I’m simply trying to show what people are like facing these kinds of choices. Because, you know, people talk a lot about the landscapes and uncanny events, but they’re all filtered through a particular character point of view. And I often ask myself, is this person open to what’s happening or are they closed? Are they in denial? Are they understanding to some degree? Are they trying to form connections or are they disconnected and alienated? These are some of the issues that we find in modern times.

How do you talk to scientists? Because this series is very science-based, but the emotional resonance of why people are drawn to science is something that comes through a lot.

My dad is a research chemist and entomologist who’s always headed up or been part of some lab, usually like fire ants and other invasive species. And so I grew up around these kinds of places. My mom was a biological illustrator for many years, and so that also brought a kind of a scientific element to her art. And between those two kinds of locations, I got to see the real human side of science.

I think that actually really helps, along with going on actual scientific expeditions with my dad to Fiji as a kid, it’s just kind of intrinsically in you at that point that you have an understanding of science. I was really quite lucky in that regard.

What was helpful to you to get this book across the finish line?

One thing that was helpful is that there’s actually a lot of humor in it. I don’t like to write books that are monotone. Even in Annihilation, in the earlier books, there’s some sly humor going on. Here, I think it’s a little more overt in some of the relationships and some of what the secret agency is doing that’s so absurd. And then in the last section, especially with this very dysfunctional, almost tech bro-esque personality that’s in this expedition. It’s kind of unintentionally funny. That’s something that anchors me, because it gives me pleasure to write, along with the uncanny stuff.

What’s the role of fiction at this point in the climate crisis?

I think one thing I don’t want the books to do when they skirt the edge of “prediction” is to be unrealistic. I get asked a question a lot, “Where’s the hope in your books?” or things like that. And it’s like, I don’t want the hope, I want the analysis. And I don’t want the faux analysis where we’re doing like carbon offsets that are meaningless. I don’t want to put that in my book as something that’s viable.

I think that what fiction adds is—it’s kind of like: What do you get from religion versus science, or what do you get from philosophy rather than science? Fiction is not science, but it can give you this immersive three-dimensional reality of what it’s like to be in a situation, and it can bring your imagination to it in such a way that it really lives in your body to some degree.

And so I think that’s why the thing that makes me most happy is having people come up to me and say that Annihilation was one reason they became a marine biologist or went into environmental science, that there was something about the character of the biologists in that book that was compelling to them. That to me, is what fiction can provide.