Chris Urso/Tampa Bay Times/AP

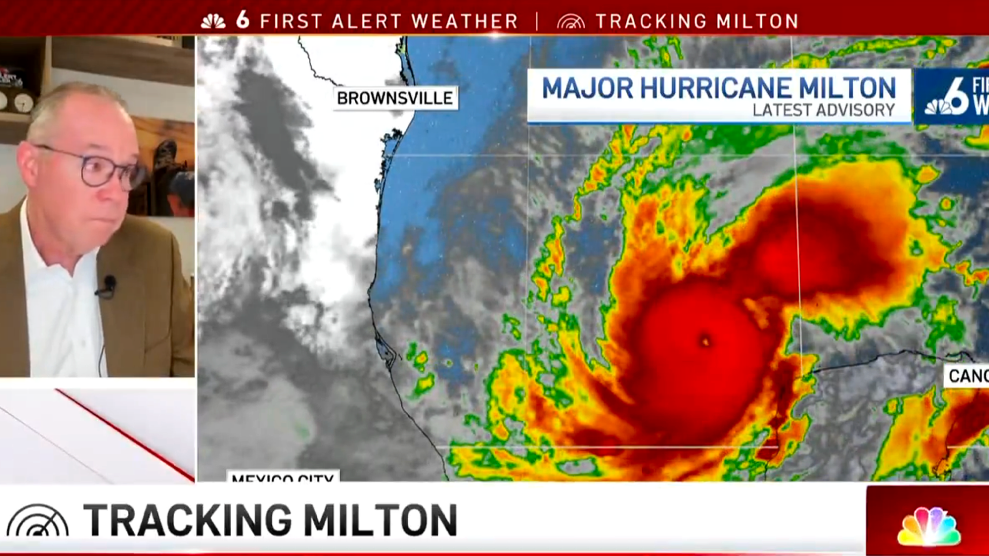

Late on Wednesday night, as Hurricane Milton made landfall, Ryan Hall, the self-proclaimed “Internet’s Weather Man,” hosted a video stream where viewers peppered him with questions about which areas looked likely to be hit, where tornadoes were touching down, and how high the water had reached in treasured parts of Florida.

“How’s Marco Island doing?”

“NORTH PORT storm surge?”

“Do you know if that came near D road? My sister has her horses there.”

The livestream featured Hall’s coverage, colleagues sharing tornado updates, dispatches from storm chasers on the ground, and a grid showing footage from cameras set up by the state of Florida, storm chasers, and other weather streamers to capture the hurricane’s arrival, landfall, and destruction. He drew in hundreds of thousands of viewers.

According to Dr. Simon Dickinson, a University of Plymouth academic who has written on livestreaming disasters, forums like Hall’s serve as digital spaces where people can ask advice, get guidance, and build a sense of community.

While there are of course viewers who could be defined as disaster voyeurs—people who want to see the “crash bang,” as Dickinson puts it—he says “there are also people there, equally, hoping that nothing happens.”

“Hazards and disasters have a new kind of cultural value.”

But Milton saw another kind of disaster streaming, with Rolling Stone documenting how the hurricane had given rise to an online “content storm” of people seeking clout by sharing video of them riding out the storm. One man decided to take on Hurricane Milton on a blow up mattress. “I’m out here trying to entertain the people in the most creative way we can,” the streamer boasted. “We started a whole new trend on TikTok. A lot of people are doing hurricane streams now. Shout out to the whole movement.”

Nearly 2 hours later, soaked by the rain, he cried “I’m done”—but only after supposedly making some $10,000.

While Dickinson notes it is dangerous for people to “put themselves in situations that they shouldn’t be for profit,” he has firsthand experience with video technology’s positive potential in a disaster. When studying for his PHd in the U.K., news broke about a tsunami alert in New Zealand, his home country. From a library he surveyed publicly available webcams, and soon realized he was “able to get more information about people and communicate to them from the other side of the world than they were able to in the event itself.”

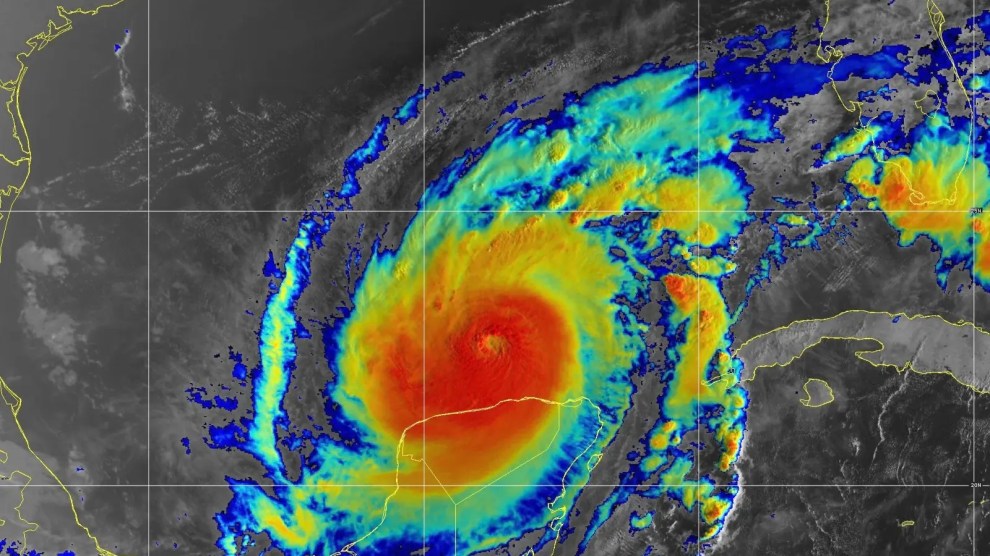

Livestream resources and other cameras are even more common today than they were at the time. Doorbells, trail cams, and even traffic cameras can be repurposed to observe a hazard or disaster. News organizations are seeing the importance of providing these resources to their audience, like the Orlando Sentinel’s straightforward list of various webcams along Florida’s Gulf Coast to witness Hurricane Milton. Live Storms Media, a company specializing in weather footage, placed new ‘Surge Cams’ in areas they expected to be hit by Milton, which now provide a stark before and after gut check. And video’s frontier keeps expanding: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shared frightening images of the storm in the gulf produced by new waterborne drone technology, capturing waves over 28 feet high.

As the popularity of hurricane YouTube streams and social media trends about assembling ‘bugout bags’ suggests, “hazards and disasters have a new kind of cultural value,” Dickinson says, which can be used as a tool “in disaster communication.” When storm watching enters boring periods—last night, a commenter on one stream complained “all the cameras I’m watching keep dying” as others were, more prosaically, blurred by raindrops—the lulls can open the door to other valuable discussions.

“Because nothing is happening, because it is quite mundane, the backdrop is very boring; naturally, conversation turns to climate justice, climate change, environmental risk,” he says.

And sometimes the conversations veer towards nostalgia as places being viewed hold some connection to commenters’ lives. In one example, Dickinson recalls two commenters realizing they had honeymooned in the same exact path of a disaster.

“The threat of a pending doom or impending loss forces us to grasp what might be lost,” Dickinson says—not just in the storm on the screen, but in the many to come.