Fifty years ago this month, President Richard Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act into law. “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” he proclaimed. The law has since helped dozens of at-risk species fully recover, including the humpback whale, bald eagle, brown pelican, and peregrine falcon, and prevented extinction for 99 percent of all species listed.

This hasn’t simply benefited those animals and plants. At the core of the effort was the desire to preserve the Earth’s living resources for the benefit of humans. “If a species, ecosystem, or ecological process, is destroyed,” Lee Talbot, one of the ESA’s co-authors and a leading environmentalist, wrote in 1980, “future generations will be denied its use.” Some 40 percent of all medicines prescribed in the United States, he wrote, are made of naturally derived ingredients. About 75 percent of the world’s food—fruits, nuts, coffee, legumes, and more—rely on wild pollinators to grow. In 2014, scientists estimated that these kinds of perks, so-called “ecosystem services,” benefited humans to the tune of $125 trillion per year—more than 1.5 times the world’s GDP at the time.

But today, much like the plants and animals it safeguards, the ESA finds itself in trouble. Whatever bipartisanship that helped the law pass easily in 1973 has since withered and died. Since the mid-’90s, mainly Republican lawmakers have launched more than 500 legislative attacks against the ESA—ranging from attempts to gut the law entirely to picking off species one by one due to industry pressure. These strikes are ramping up; 80 percent of them occurred in the past 10 years.

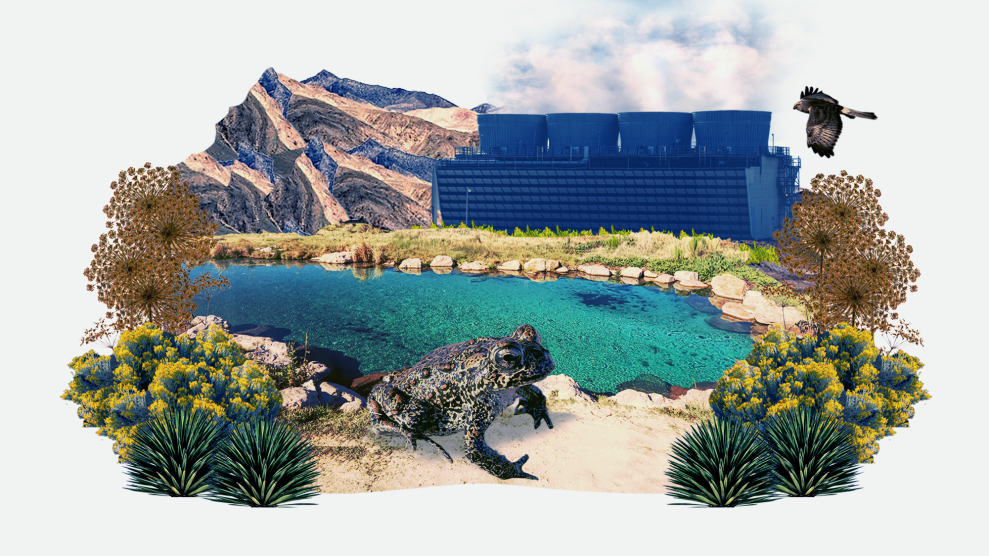

This package of stories, Endangered, highlights some of the ways the 50-year-old law is under threat from many quarters: from corporate greed, political weaponization, the climate crisis, garden-variety government bureaucracy, and even weak spots in the law that have undermined it from within.

As I discovered while reporting a dispatch about the Venus flytrap, the ESA is designed to be nature’s “emergency room,” but it does little to protect species from landing there in the first place. Some say it has been deployed as a political cudgel, as my colleague traces in a piece about two threatened mussels caught in the crosshairs of a battle over a border barrier. And it has been used, at times, as in the case of a toad and a geothermal plant, to block renewable energy projects that some argue would help endangered species by reducing emissions. The law is burdened by an absurdly long waitlist, where species often languish in limbo for more than a decade—and sometimes become extinct in the waiting room. And, as one of my colleagues writes, it’s fueled our (perhaps unhealthy) reliance on zoos.

That’s not to say the act isn’t powerful. In fact, the experts I spoke with say we need this “pit bull” of a policy more than ever: In the last half-century, the planet has lost about 70 percent of its wildlife, and more than a million species are nearing extinction. As the country’s preeminent biodiversity law, the ESA may be the best existing tool to safeguard disappearing plants and animals—if we can save the act from ourselves.—Jackie Flynn Mogensen

Project credits

Lead reporter: Jackie Flynn Mogensen

Project editor: Maddie Oatman

Reporters: Henry Carnell, nia t. evans, Nina Wang

Story editors: Kiera Butler, Nina Liss-Schultz, Daniel Moattar, Maddie Oatman, Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

Fact-checkers: Henry Carnell, Katie Herchenroeder, Nina Wang

Copy editor: Daniel King

Photo editor: Mark Murrmann

Multimedia producer: Sam Van Pykeren

Art directors: Michael Foy, Adam Vieyra

Illustrator: Michael Foy