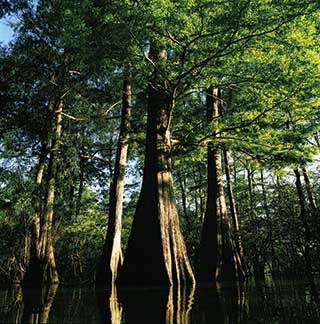

Getty Images

This story was originally published by Yale Environment 360 and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In 2007 an Idaho couple, Mike and Chantell Sackett, bought a building lot across the road from a wetlands complex that drains into a creek and then into Priest Lake, with plans to build a new home. They began to fill in a spot on the property with gravel and sand until the US Environmental Protection Agency stopped them under authority of the Clean Water Act, claiming it was a wetland adjacent to the lake. They were told to remove the fill and reclaim the site by fencing it off for three growing seasons. Failure to do so would cost them more than $30,000 in fines each day.

The couple refused and sued the EPA in 2008, arguing that their property was not wet. It touched off a lengthy legal saga that continues and has now come before the US Supreme Court for the second time. The case first reached the Supreme Court in 2012 on the question of whether the Sacketts had standing to challenge the EPA in federal court. They did, the court ruled.

When their suit came again before a federal court in 2019, the judge ruled the EPA could require the permit, and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that decision. The Sacketts, whose case has become a cause célèbre for the property rights movement, appealed to the Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments as the first case of this term. A decision is expected next year, and it may clearly define what a wetland is—for good or ill, depending on one’s perspective.

Currently, the law governing wetland protection is muddled. The Clean Water Act of 1972 holds that federal protections apply to navigable waters, which are referred to as the “waters of the United States” (known as WOTUS). Wetlands often aren’t navigable, yet they help keep navigable waters clean and healthy. The Clean Water Act left it to federal regulators to determine exactly what should be should be included under “waters of the United States,” and court decisions have so far failed to clarify the issue.

A previous Supreme Court case, in 2006, only added to the confusion when the opinion split three ways. A plurality of justices, in an opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia, found that a “continuous surface connection” was the test to define a wetland to find protection under the Clean Water Act. But a separate opinion, by Justice Anthony Kennedy, found there needed to be a “significant nexus” to navigable waters, which means that if there wasn’t an obvious surface connection, research was needed to show that the wetlands played a role in assuring the integrity of the larger body of water, for wildlife habitat or for other ecological value.

Subsequent decisions by lower courts have said that either Kennedy’s opinion should be followed or that either opinion may be used. This lack of clarity has meant the protection of isolated US wetlands has been uneven, experts say. While those with a direct connection to navigable waters have largely been protected by the EPA and the US Army Corps of Engineers or had their development somehow mitigated, those without such a direct connection—like the Sacketts’—have been protected in some places and not in others.

The upcoming Supreme Court decision could settle that ambiguity and bring major changes to how wetlands are managed in the US Legal experts say the ruling could be transformational for the nation’s remaining bogs, swamps, and ponds. “This case has the potential to drastically the reduce the number of wetlands that would be protected,” said Amy Sinden, a professor of environmental and property law at the Beasley School of Law at Temple University. “It depends on how they word [the decision]. It’s unclear where they would draw the line.”

Until the 1970s, the nation’s vast array of swamps, marshes, ponds, and bogs were seen primarily as a barrier to progress, and few saw importance in their natural value.

The soil beneath a wetland is high in nutrients, which makes it prime farm land. The Swamp Land Acts in the mid-19th century transferred wetlands to states if they agreed to drain that land and put it into production. Some 20 million acres of the Florida Everglades were drained as a result. Before European settlement, the lower 48 states had 221 million acres of wetlands; slightly more than half of those are gone and continue to decline, at the rate of about 60,000 acres a year.

American attitudes toward wetlands began to shift markedly in the 1970s, with raised awareness about the state of the nation’s water quality and the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972. Wetlands are important green infrastructure; among other functions, they are essential to clean water because they remove sediments and pollutants, including chemicals and excess nutrients from fertilizers, sewage discharges, and other sources.

Globally, wetlands provide critical ecosystem services worth $47 trillion a year. This includes buffering shorelines, reducing the intensity and frequency of flooding, cleaning and storing water, and reducing soil erosion. They store more carbon, acre for acre, than other ecosystems, both in the plants that grow each year and, in the long term, in the soil where carbon stores are hundreds or thousands of years old. Wetlands in and around urban areas capture and store excess and polluted runoff from impervious urban surfaces, such as rooftops and pavement.

Found in a wide variety of habitat niches, wetlands are one of the highest functioning ecosystems in the world, comparable to coral reefs and tropical rainforests. They support a wide array of biodiversity, from fish to insects and birds. Some 40 percent of all species depend on wetlands for part of their life cycle.

President Jimmy Carter issued the first federal protection specifically to wetlands in 1977. It was under the administration of George H.W. Bush, an avid duck hunter, that wetlands were given greater priority when the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers in 1989 established a policy of “no net loss” of wetlands. The policy sought to prevent further loss of wetlands, either by protecting them from development or mitigating the loss by creating or protecting other wetlands in their place. That policy has been renewed by subsequent presidents and is still in force.

Yet wetlands are still in decline.

Climate change is part of the threat, though it’s a mixed bag. “The whole world isn’t going to dry up,” and wipe out wetlands, said William Kleindl of Montana State University in Bozeman, who is president of the Society of Wetland Scientists. “[But] the weather patterns are going to shift all over the place.”

Because the atmosphere is holding more water in some regions, there is more precipitation than usual, which is keeping wetlands thriving in those places. But in other regions, such as the American West, much of which is in the grip of a 20-plus-year megadrought, drier and hotter conditions are taking a severe toll on the wetlands that remain after agriculture and other development has eliminated most of them. California, for example, only has 5 percent of its original wetlands.

In the critically important migratory bird habitat in the Klamath Basin in Oregon, the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuges have seen 40,000 acres of wetlands diminish to 5,000 acres, for example, and around the drought-devastated Great Salt Lake most of the half-million acres of natural and managed wetlands are dry this year.

In North and South Dakota and across the northern Great Plains, prairie potholes are disappearing, drying up because of heat waves, droughts, or because they are not considered near enough to “navigable waters” to warrant protection and permitting under the Clean Water Act.

Climate is taking a toll globally. Spain’s vast Donana Santa National Park is considered natural jewel and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve. Millions of birds stop in these 182,000 acres of wetland on their migration from Africa to parts of Europe to rest and feed. Recreational development, farming, record-high temperatures, and prolonged drought last year have dried up much of the lagoon.

Sea level rise driven by climate change is also taking out coastal wetlands. On the coast of southern France, sea level rise is moving salt water into grazing land among wetlands, and grass no longer grows there. On the Atlantic coast in the southeastern US, rising saltwater is moving into wetland forests and killing them faster than they can replace themselves. These “ghost forests” are spreading.

Development, for agriculture and building, continues to account for the lion’s share of the losses. The first line of defense for wetlands is to prevent their development. If that is not possible, mitigation is the next step. That might mean creating new wetlands to replace those being lost. “If [mitigation efforts] are done right, they can replace a lot of the function of other wetlands,” said Jim Murphy, an expert on wetlands for the National Wildlife Federation. “The trick is making sure they take, because a lot of times they don’t. It needs monitoring and enforcement.”

Under federal regulations, developers can pay a “wetland mitigation bank” to buy or enhance wetlands or create new ones to compensate for protected wetlands lost to development. But that can sacrifice the local benefits of a wetland. “Our closest wetland bank to Bozeman is in Twin Bridges, which is 90 miles away,” said Kleindl, of Montana State. “Fifty percent of all the birds in Montana use wetlands riparian areas for part of their life cycle. You can compensate in Twin Bridges, but a bird watcher has lost an ecosystem service in Bozeman.”

The Supreme Court decision in the Sackett case is expected next spring or early summer. Silden, of the Beasley School of Law, said some court observers who heard the arguments said that, based on the comments and questions from some of the conservative justices, the ruling by the conservative-led court may not be a foregone conclusion. “The oral argument was a bit of a surprise, and a number of people came away from that oral argument thinking there is some chance you will get an unusual coalition on the court,” that may not impinge on wetland protection, she said.

If the Supreme Court does remove or limit federal protection for some wetlands, it would then be the states’ responsibility to protect them. “If they go with what the plaintiff put forward or even something less extreme, it could mean the elimination of Clean Water Act protections for about half of the nation’s wetlands,” said the National Wildlife Federation’s Murphy. “The majority of states have no or virtually no protection, and it would then be open season on wetlands.”