The lesser spotted eagle is endangered in Germany.Hinze, K/DPA via ZUMA Press

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Small in size, sensitive of constitution and with only 130 breeding pairs surviving locally in the wild, the lesser spotted eagle of the Oder delta lives up to its name. In Germany, key questions over the country’s energy future hang on the question of whether artificial intelligence systems can do a better job of spotting the reclusive animal than birdwatchers do.

Lesser spotted eagles (named after the drop-shaped spots on their feathers) are fond of riding thermals over many of the flatlands earmarked for a mass expansion of onshore windfarms by a German government under pressure to compensate for a pending loss of nuclear power, coal plants and Russian gas.

Because lesser spotted eagles in mid-flight are unused to vertical obstacles, and keep their eyes focused on mice, lizard or frog-shaped prey below, conservationists say, they are known to occasionally collide with the rotor blades of wind turbines. German researchers list eight dead specimens found in the vicinity of windfarms since 2002, a small but not insignificant number given the species’ endangered status in the country.

A controversial reform of the federal nature conservation act, pushed through by Olaf Scholz’s coalition government earlier this summer, slashes red tape around building windfarms near nesting sites, but banks on AI-driven “anti-collision systems” as one way to minimize such accidents.

Software engineers in Colorado are feeding hundreds of thousands of images of the airborne clanga pomarina into an algorithm. Linked to a camera system perched atop a 10-meter tower, the trained-up neural networks of the US company IdentiFlight are expected to detect eagles approaching from a distance of up to 750 meters and electronically alert the turbine.

The turbine will then take 20-40 seconds to wind down into “trundle mode” of no more than two rotations each minute, ideally giving the eagle plenty of time to navigate safe passage between its slowly moving blades.

IdentiFlight spent three years testing its anti-collision systems at six supervised sites across Germany, and says its neural network boasts rates of more than 90 percent for recognizing and classifying red kites, the first birds of prey it has been trained in for German territories. While fog, rain, or snow can reduce the system’s effectiveness, the makers say, low visibility also decreases the eagles’ appetite for airborne hunting raids.

The system is expected to be certified for spotting sea eagles in the coming weeks, with validation for their lesser spotted relatives scheduled for 2023. “From our point of view, the system could be a good solution,” said Moritz Stubbe, a business manager trying to bring anti-collision systems to German wind parks. “We are waiting for the green light.”

The technological solution is also meant to solve a political conundrum for the Green party, the second-largest party in the three-way coalition government and driving force behind the new nature protection law. By keeping the peace between those of its supporters who define ecological politics predominantly as safeguarding biodiversity and those who prioritize mitigating the climate crisis.

Wind energy in Germany underwent a massive boom after Angela Merkel announced the phase-out of nuclear power in 2011, with windfarms currently providing about a quarter of the country’s electricity needs. But the expansion plans have stalled for the past four years, at about 30,000 turbines providing just over 60,000 megawatt hours a year.

Wind power companies complain that planning applications take longer and longer, with not only environmentalists but locals opposed to turbines having learned to use natural protection laws to stymie their plans.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended decades of German energy policy, Scholz’s government had announced its intention to reverse the trend: it has plans to increase electricity from renewables by 80 percent over the next eight years, and to commit Germany’s 16 federal states to provide 2 percent of their landmass for wind energy over the next ten. Experts say this would amount to an additional 16,000 turbines by 2030, or 38 a week.

To reach these targets, Germany’s Green-run environmental ministry has for the first time drawn up a conclusive list of 15 birds it deems at risk of colliding with turbines. Those animals that did not make the list, such as the black stork, cannot be cited to stop a planning application. But even those that did make the grade are now protected to a lesser degree.

Windfarms can in the future be built outside a 1.5 kilometer radius around the nest of the lesser spotted eagle, for example, down from 3 kilometers. In the north-eastern state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, conservation officers said this is likely to affect 10 nesting pairs.

Wind park developers may still be obliged to take additional measures to protect the at-risk birds, such as by switching off turbines while fields in the vicinity are being harvested, thus attracting birds of prey on the lookout for newly exposed field mice.

Switching off turbines for an entire breeding season, however, will no longer be allowed, and rotor blades are not allowed to be kept at standstill if the farm’s energy production is diminished by 4-8 percent as a result, depending on the location.

“It’s a catastrophe,” said one nature protection officer who did not want to be named, suggesting the legislation was likely to be disputed and thus bog down planning applications rather than unleash turbine builders. Some lawyers argue the new act violates European environmental law; the German Wind Energy Association (BWE) vehemently disagrees. Court action looks predestined.

“As a society, we have to start asking ourselves some basic questions,” said Wolfram Axthelm, BWE’s chief executive. “Do we want to build windfarms because we want to mitigate climate change and protect the environment as a whole? Or do we want to save every individual bird?”

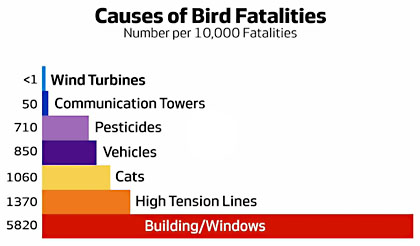

The number of birds killed by wind turbines, he said, was dwarfed by those that perished after flying into windows, being run over by cars or being caught by domestic cats. “We have to concentrate on the population as a whole.”

Clanga pomarina is named after Pomerania, the historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. In Germany, the lesser spotted eagle’s population has declined by a quarter since the 1990s, not mainly due to wind turbines, but to a gradual disappearance of the woodland-meets-wetland habitats where the birds like to nest.

Further to the east, in Estonia, Lithuania and Slovakia, the species is still thriving. The International Union for Conservation of Nature red list of threatened species lists the lesser spotted eagle’s global population as stable, with an estimated 40,000-60,000 mature individuals remaining in the wild