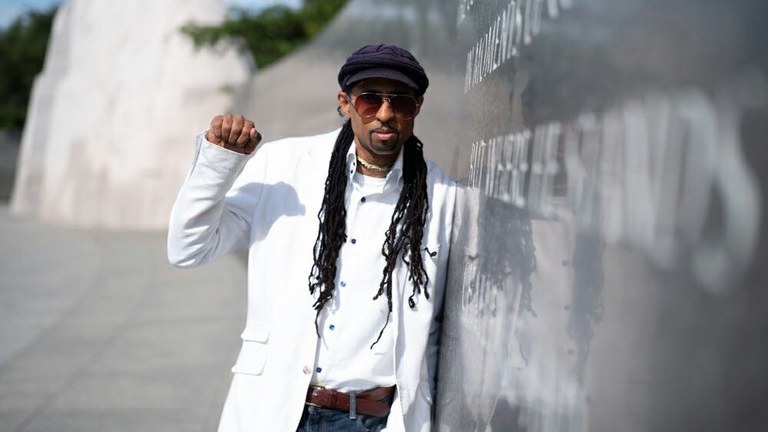

Having departed the EPA under President Trump, Mustafa Santiago Ali is now vice president of environmental justice at the National Wildlife Federation. Courtesy image

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

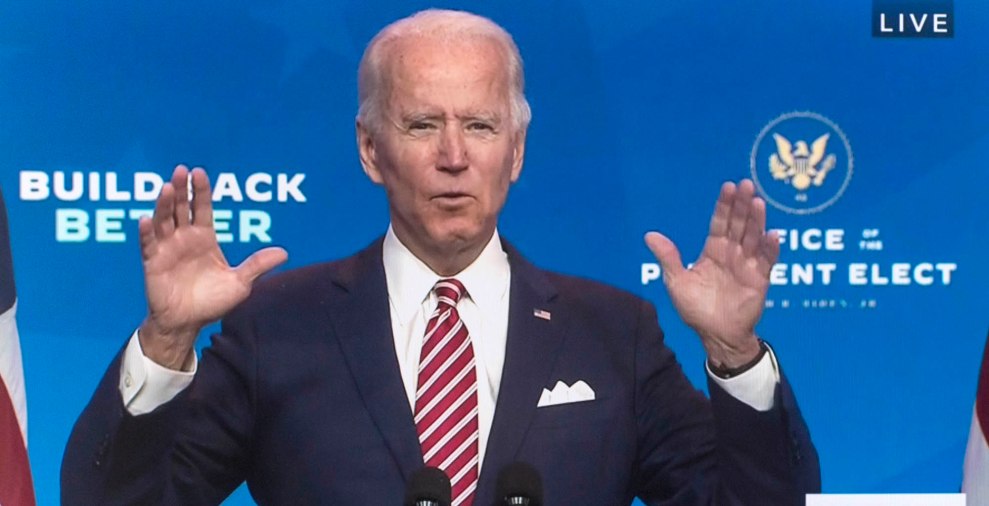

A cap-and-trade system to cut toxic air emissions; a bipartisan agreement to strengthen the Clean Air Act; a federal program to ease the unjust burden of pollution in minority communities: All this sounds like an environmental to-do-list for President-elect Joe Biden. But it’s actually a list of federal actions taken by the George H.W. Bush administration in the early 1990s.

Mustafa Santiago Ali joined the Environmental Protection Agency in 1992, during Bush’s tenure, as part of a program to get college students from minority communities more involved in environmental issues. Over his 24-year career with the EPA, Santiago Ali helped lead the agency’s environmental justice programs, working to undo the toxic burden of pollution in minority, Indigenous and poor communities.

Then, in 2017, the Trump administration upended the program, proposing to zero-out its budget. Santiago Ali left the agency. He’s now the vice president of environmental justice, climate and community revitalization at the National Wildlife Federation. There, he has helped lead the conservation community’s growing efforts to recognize the racist legacy of the predominantly white-run world of big green organizations.

High Country News spoke with Santiago Ali about the Trump administration’s impacts on the federal government’s environmental justice work, and how President-elect Joe Biden could reset that agenda. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

High Country News: What is environmental justice?

Mustafa Santiago Ali: It deals with the disproportionate impacts that are happening in communities of color and lower wealth and on Indigenous land—from exposures to pollution, to the lack of access to the decision-making process. It is the creation of these sacrifice zones that we have across our country, where we place everything that nobody else wants: coal-fired power plants, incinerators, petrochemical facilities and waste treatment facilities.

Communities of color, low-wealth white communities and Indigenous folks are often the ones dealing with this and having a difficult time being able to access basic amenities: clean air, clean water and clean land. The disparities are also that in many instances in the past, they have not had an active seat at the table in the framing-out of policy and the prioritizing of their communities. That’s the environmental injustice—the environmental racism—side.

The environmental justice side is: How do we help communities move from surviving to thriving? How do we revitalize communities? How do we help to build capacity and power inside of those communities so that they are no longer seen as dumping grounds, but as healthy, vital and sustainable communities?

HCN: How has environmental justice work evolved within the federal government over the last two and a half decades?

MSA: It’s always been more about the communities, because they’re doing the work seven days a week, 24 hours a day. The role of the Environmental Protection Agency is to help communities better understand (laws and regulations) and how those are supposed to work and how to utilize them. It was about helping to get the science in place, helping people to understand various policies, and getting other offices in the agency to integrate environmental justice (into their work). It’s also about making sure that enforcement is happening, especially in communities that have often been unseen and unheard.

The work ebbed and flowed. Under certain administrations, there was more of a focus on environmental justice, and for others, not as much. But never anything like you saw in the Trump administration, where they tried to destroy all the work that had happened over the years around environmental justice and other program offices that are critical to the work that front-line communities are doing and need help with.

HCN: Can you explain what that destruction looked like inside the EPA?

MSA: Years and years of work went into building relationships with communities, and that trust has been broken. That has its own set of ripple effects. Folks have lost confidence. The current administration decided to take steps backwards with the Clean Car Rules and the Clean Power Plan, and all these things that they didn’t see any value in.

Folks inside the agency have been really concerned that enforcement has not been happening to the level that it needs to be to make sure that (communities) are being protected. Folks have also been really disappointed in how science has been weakened. Unfortunately, the current administration has not honored science.

Also more recently, the executive order and then the memo that came out that said, “You can’t talk about race.” When you’re trying to figure out the best way to keep people protected through policy—and you’re saying that systemic racism is not a factor—then it makes it really difficult to address environmental racism and environmental injustices.

HCN: What do you think is the most important step to rebuild trust?

MSA: To rebuild trust means you have to spend some time with folks. They’ve got to know that their voices are being honored in the process, and that they are a priority in what’s going to be developed, and they’re playing a role in that. You’ve got to honor science, but that science comes in lots of forms and fashions. There are the traditional science models that we operate from, but there’s also that science that comes from traditional environmental values that our Indigenous brothers and sisters bring. There’s science that comes from community-based participatory research. Many communities are doing their own sets of analyses and have their own sets of suggestions and solutions to minimize many of these impacts that are going on.

When we talk about rebuilding the capacity, we’ve got to make sure that those who come from front-line work, who are interested, have a real opportunity with some of these jobs that will be opening up. You really need a diversity of ideas and a new set of innovation and ingenuity.

I really appreciate the Biden administration saying that it’s an all-hands approach, where all of these federal agencies and departments are going to have a role to play. Because if you really understand environmental justice, and the work that happens in that space, you’re talking about housing and Housing and Urban Development, and the Department of Transportation, and Health and Human Services, and the Centers for Disease Control, and the Department of Labor, and so forth and so on.

HCN: What would be a sign that the federal government’s on the right path toward environmental justice?

MSA: Words are important. I’m hopeful that our new president will be sharing with the country the commitment in that space. And, then, also seeing a couple things: One is people building their budgets and making some financial choices. They’ve said environmental justice is a priority, so we’ll see that play out, and how resources will flow.

The other part will be on the capacity side, both in the White House and in the agencies and departments. When I was in the federal government, I was the only senior advisor for environmental justice for the entire federal government, which just doesn’t work. I mean, you can get things done, but you need to have senior advisors in each of those agencies and departments as those secretaries and administrators are making budgeting decisions and policy decisions, so there’s real representation there.

HCN: What do you think is most important for moving the cause of environmental justice forward?

MSA: A set of opportunities I definitely want to highlight is: How are we going to properly engage young people? All these incredible young leaders across the country have invested so much in trying—whether it’s environmental justice or the climate crisis—to get actions and solutions in place.

Hopefully, we will now be moving into a time when we don’t have to deal with so many egregious sets of actions. We’ve spent enough time just trying to push back, and, you know, we only have so much energy. I wish we would’ve spent that time on moving forward and not continue slipping backwards and backwards.

So I’m looking forward to, you know, doing what I can, and also seeing how all this plays out over the next four years. By the time we get to the end of this administration, we’ll know. It’ll be very clear if we’re going to be able to win on climate change. Hopefully, we’ll be more clear also on where our country stands on racial justice issues. Because, I think, on both of those, the sand in the hourglass continues to tick down, and hopefully, we’ll end up on the right side of history.

Note: This story has been updated to clarify that Mustafa Santiago Ali did not join the EPA until he was a college student in 1992.