Obi Kaufmann/Heyday Books

California is burning. After a rare lightning storm during an exceptional heatwave sparked more than 350 blazes in August, hundreds of thousands evacuated their homes as 6,223 structures were damaged or destroyed and 25 lives were lost. One month later, four of the five largest wildfires in the state’s 170-year history are still raging.

As in recent years, residents have been stuck indoors for weeks as they struggle to take a breath of fresh air beneath skies clogged with ash and dangerous particulate matter, reluctantly learning to call this the “new normal.” Yet the record-setting 3.5 million acres that have burned so far this year are only beginning to stack up against the “normal” of pre-colonial times, when 5 million acres or more burned every year due to a combination of lightning strikes and intentional ignitions by Indigenous people. What makes today’s mega-fires different is not so much the quantity but quality: California is burning more intensely, in ways it never has before.

California writer and naturalist Obi Kaufmann has paid careful attention to this shift. Born and raised in California, he’s spent decades roaming the state’s backcountry, getting to know plants and animals intimately as he paints their portraits in watercolor. His 2017 book The California Field Atlas enchanted lovers of the state with artful descriptions of its interlocking natural systems. His unique style aims to promote “geographic literacy,” which Kaufmann describes as “the responsibility of every citizen who loves this place, or who is falling in love with it, to learn perhaps more than just a bit of its functioning ecology. People protect what they love, and people love what they know and understand.”

Artist, writer, and naturalist Obi Kaufmann.

Heydey Books

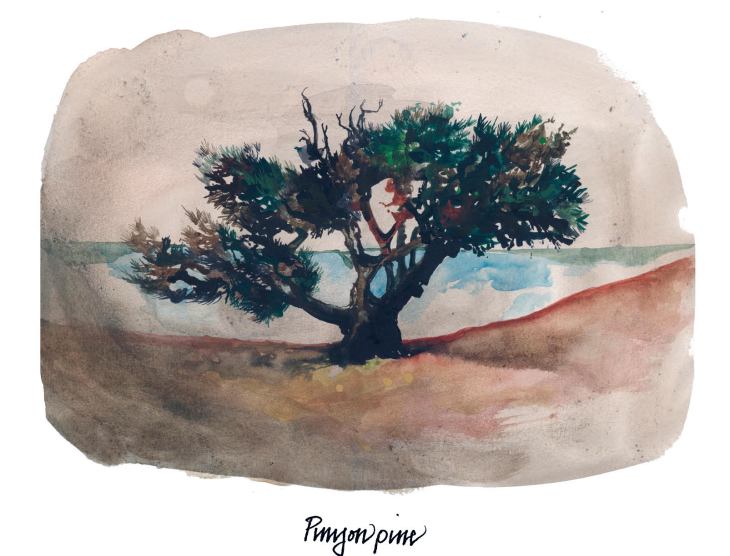

This month, he published The Forests of California, the first in a trilogy of field atlases that will also explore coasts and deserts. The book zooms in on the state’s wide range of forest ecosystems, weaving scientific descriptions of tree species with the histories of their ancient ancestors, telling a story of California’s biodiversity that has evolved over hundreds of millions of years.

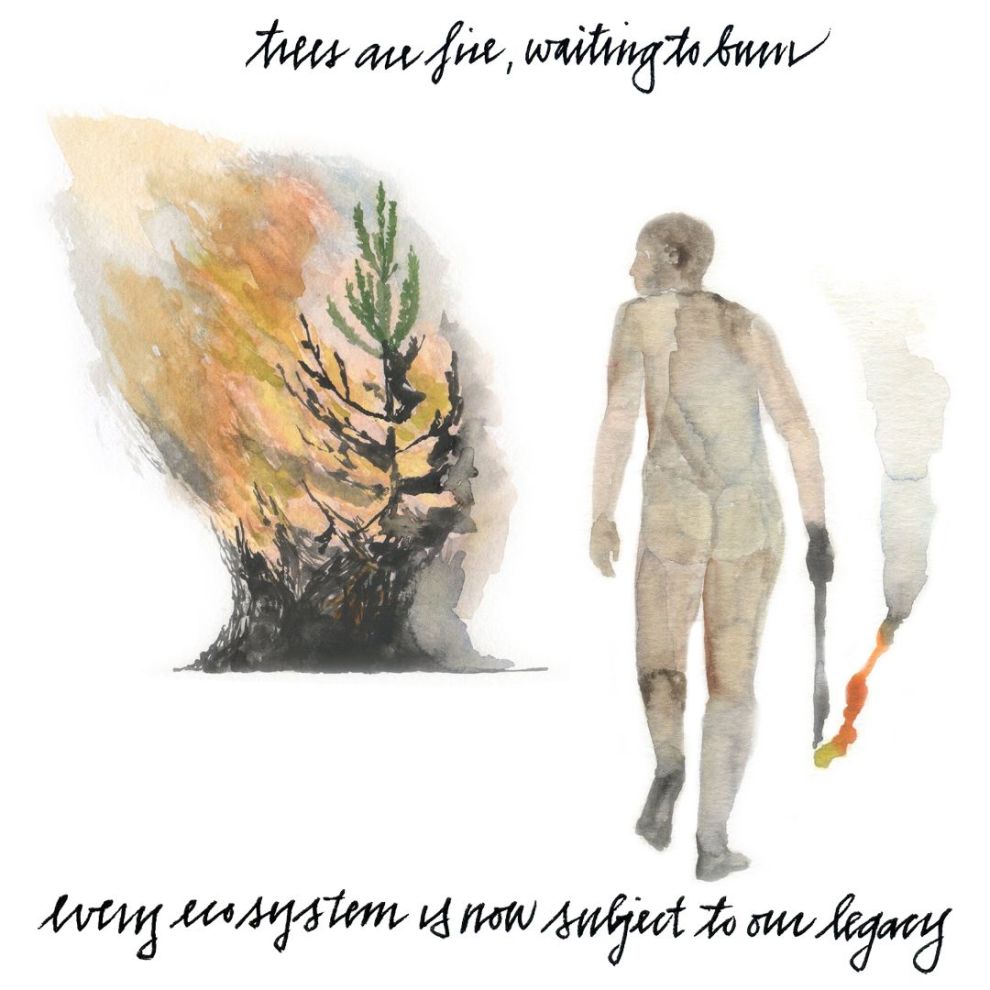

That evolution has always relied on wildfires. As he writes in The Forests of California: “Without fire, California is not California. This is a lesson that will get more intense in the century to come.”

With work that swirls research with poetry, the personal and human with the collective and ecological, Kaufmann seemed a natural person to talk to during what feels like great calamity—but may also represent a return to the land’s natural rhythms. “California holds its breath between moments of deluge and moments of inferno,” he writes in handwritten cursive. “There is a terrible and beautiful moment before the hammer strikes and we are then both made and unmade, holding hands and holding the line and learning always when to let go.”

I reached out to Kaufmann to ask him about his new book and his reflections on the current blazes. He was at his home in Oakland, twenty miles west of where we both grew up in the shadow of Mt. Diablo.

In your book I learned that just a few thousand years ago, much of the Northern Hemisphere was one to two degrees Celsius hotter than it is today. You describe the difference between climate change, which has always happened, and climate breakdown, which is the intense new thing we’re living through. If life can adapt to such variable conditions, why are we now facing a breakdown?

You’ve heard the climate denial argument that “the climate is always changing.” Yeah, but it’s the rate and frequency of how it’s changing which is the problem, and I think this gets to the larger vocation of my study, which is a holistic ecological approach. Climate breakdown is expressing itself through chaotic amplitudes: Weather conditions which might have once existed every ten years, now exist every three years, perhaps even every year. In California, we have decreasing intervals between drought events, and perhaps counter-intuitively, more rain coupled with more aridity at the same time. That is a potentially disastrous recipe. And certainly look at the sky right now, this is absolutely climate breakdown. [On the day we talked, the sky was a grim shade of orange].

You also have to consider that human development and biological invasiveness over the past 170 years—since that guy found that pretty rock in that river, the Gold Rush—have so radically changed the regime across the hydrosphere, the atmosphere, and even the lithosphere, when we look at soil health, that you can’t talk about fire without talking about all those other things too. You introduce things like Eurasian grasses that livestock-dependent people have carried all over the world, which came to California with the Spanish 500 years ago—12 to 18 different species of invasive grass that like to burn every year. That’s how they seed, and they’re very good at transforming forests.

The adaptive cycle, the natural clock of when fires happen, starts to break down. Ecological succession becomes ecological conversion. And that’s a dangerous trajectory, if you like things like douglas fir/redwood forests. Keeping out invasive species and acknowledging the endemic adaptive cycles is a challenge.

The story that will guide us to, among other things, a more coherent policy towards preservation of this perilous and beautiful place perhaps into the 22nd century, is examining the larger network interactions and how they coalesce. If our intention is to preserve working ecosystems and their functions and services for the next 100, 200, 500, 10,000 years, do we then not only talk about endangered species, but perhaps endangered habitats? And if that’s the case, maybe we should even talk about endangered ecological phenomena, such as coastal fog, which our coastal redwood forests depend on.

Scenes from around San Francisco where dark orange skies are still blanketing the city and region.

This apocalyptic hue is due to a combination of smoke from various wildfires sitting above the marine fog layer. More here on @sfchronicle https://t.co/eChDMsLZLs pic.twitter.com/VaQlNsML0y

— Jessica Christian (@jachristian) September 9, 2020

You write in the book that “smoke filled skies have long been a fact of life in California.” What makes the natural and Indigenous fire regimes of the past different from what we’re seeing today?

All of these vocabulary words like “good fire” and “bad fire” are sprouting up in popular rhetoric, and that’s fantastic to witness. What a great moment to tell this story—and to pick out the right words. For example, the difference between “intensity” and “severity,” which are two very different things when you’re talking about how fire behaves.

Look at the ponderosa pine with its long needles. It loves an intense fire, but it doesn’t love a severe fire. It will burn hot; those needles and all that dry duff [decomposing organic matter on the forest floor] are ready to go in a flash. But if the ponderosa forest is crowded with these even-aged white fir trees that tend to crowd around the tree, then they act as ladder fuel and carry the fire up into the canopy. That’s where the ponderosa pine begins to shrink in its ability to be resistant.

There’s a few places like the Santa Monica Mountains down south that have had too much fire. The habitat has not been able to recover. But Northern California is fire deficient. It’s thirsty for fire, which is counterintuitive, but when you look at the numbers a startling picture appears: In pre-colonized California, under a combination of anthropogenic fire regimes (the millenia-old technology of stewardship by Native Californians) and lightning strikes, we’re looking at four to five, perhaps even upwards of 10 million acres burning per year. That sounds like a lot, but consider that back then, you had widely spaced arboreal habitats. The trees aren’t close together.

In the past, you had fires averaging 500 acres, with an intense burn zone of about 10 acres. You look at any of the great fires of the last 10 years, and they’re averaging 275,000 acres, with intense burn zone of 30- to 50,000 acres, where the soil itself is in threat of actually being sterilized from the severity.

This is probably the biggest point I can make towards our own agency within this helpless posture that we’re all carrying right now, under our smoky skies as we’re blinking through our tears: However radically the land has been transformed in the past 170 years, it will be matched by its future transformation in the next 170 years. It is going to get worse before it gets better. But I can say with confidence that today’s catastrophes clothe tomorrow’s children in wisdom.

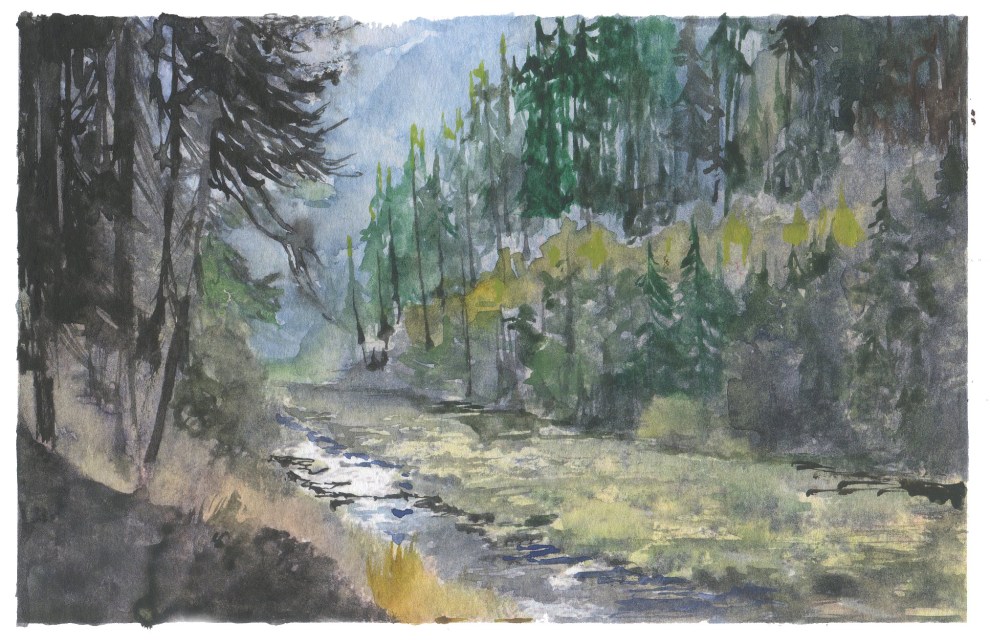

A mixed conifer forest along Scott Creek in Santa Cruz County.

Obi Kaufmann/Heyday Books

In the long run, will the fires we’re living through today make the forest more resilient?

The data is still out, but as shockingly as we’ve witnessed these mega-fires, we’re also witnessing an equal and opposite regeneration within the forest body itself. I think about how we watched the Rim Fire of 2014 over the past six years. We’ve watched the forest quickly green, regenerate, and re-establish many normalized characteristics that we saw before the fire. I’m thinking of the great tragedy of what has happened to Big Basin State Park, the largest piece of old-growth redwood forest south of the Golden Gate—the fire that moved through there was quite severe, and yet it looks like the big trees have survived. [But] trees surviving and habitat surviving are actually two different things.

Think of a similar sort of ecological disturbance, when we—the colonizers—destroyed 95 percent of old-growth redwood habitat in a period of about 70-80 years, in the 19th and 20th centuries. You go back there now, and I think the untrained eye would say, ‘hey, look at all of these tall trees!’ It turns out that coastal redwoods get most of their height within the first 200 years of their life. So the forest height comes back, but the habitat is gone. A lot of the creatures are now endangered species, like the marbled murrelet or the spotted owl, or the Humboldt marten [which recently won protections under the federal Endangered Species Act]. We see the forest coming back, but changed. It’s as if the forest has lost its mind, it can’t remember its own habitat.

Another major ecological imbalance is California’s massive, ongoing tree die-off. Can you explain what’s happening, especially in the Sierra Nevada, and how it’s changing those ecosystems?

Our forests are infirm and the tree mortality rate is unprecedented. You hear people say, “we need more trees,” but right now there are more trees in California than there have ever been. It’s not more trees that we need, it’s healthier forests. Healthier forests are better at doing things like sequestering carbon. You have all of these trees that are sucking up water, contributing to this cascading effect of of great aridity and more stressed trees, which means more insects that come to feed on and kill them. We’ve got an overpopulated and unhealthy forest. With the slight uptick in aridity based on climate breakdown, you have forests running upslope in the San Bernardino National Forest, retreating upslope by 200 feet in one century.

We have this wonderful opportunity to again decide what is worth what. We want the forests to be healthy and to perform their ecosystem services, which include delivering us water—the Sierra Nevada is our water tower, we get almost half of our water across the state from that snowpack, and a healthy forest retains snow better than a crowded, infirm, diseased, fragmented, simplified forest.

So taking care of the more-than-human ecology is really taking care of our own resiliency. Whether we can turn to this story remains to be seen, but things are changing very rapidly, and that is why I do this. It’s not because I have any sort of despair, that I am out of my mind with worry. It’s because for every point of despair that I see, there is a point of hope.

I would like to contribute to a better story, which is an older story, which is also the story of our future, about how every one of our rights is balanced by an equal responsibility. I think that geographic literacy, which is the whole point of these field atlases, means that it is the responsibility of every citizen who loves this place or who is falling in love with it to learn perhaps more than just a bit of its functioning ecology. People protect what they love, and people love what they know and understand.

It’s becoming apparent that routine burning can help us protect our ecosystems, yet you write in your book, “regardless of how much fire is required to maintain healthy forests, overriding the very human worry, concern, and trauma will never be an option.” What did you mean by that?

What I mean is that we have perhaps a physiological response, as the mammals that we are, to the grand thing that is fire. I hope that I was not implying that we’ll always see fire as the enemy. The Indigenous people of California have a very different relationship to the idea of fire as a gift or a tool towards, for example, the manufacture of food—a farming tool. Forests, it turns out, are not very good at making food. Open meadows, sunshine, healthy soil: This is this is where the food happens.

Our relationship to fire is very difficult, our relationship being the colonizers’ relationship. There was a time when California’s policy towards fire suppression was actually a tool of colonial violence against Native Californians. I think that very important historical concept should be unpacked and drug out into the light. It not only gets to our attitude towards forests, it gets to our attitude towards wilderness. It’s a sacrosanct concept in most environmentalists’ minds that the 1964 Wilderness Act establishing the federal wilderness system is untouchable, when in fact we have to seriously re-examine even that, towards what I believe is a coming paradigm shift based on ecology.

Rights, responsibilities, stewardship—all of these concepts are transforming, and just as the forests are burning, so are we. There is a reckoning, and I love that word “reckoning” because it’s almost a reconnecting, between our economics and the relationship to justice—not just environmental justice, but racial justice, and how that then translates toward our responsibilities to acknowledge consciousness, mind, and sentience within the forest. We are witnessing the grand transformation and reset of the forest body, and our capacity to do the same.