BP logo.Beata Zawrzel/Zuma

This piece was originally published in Grist and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

If only there were an app that would let you track your personal carbon footprint in real-time, like a FitBit. You could watch the weight of your emissions grow as you drove to the store, took a bus to the park, or rode the train around town. As the number ballooned, the app would prompt you to assuage your guilt by buying carbon offsets—helping programs that promote biogas in Indonesia, cleaner cookstoves in Mexico, and tree-planting in the United Kingdom.

Now imagine that app was funded by an oil company.

That’s the real-life story of VYVE (rhymes with “five”), one of a handful of new carbon-tracking apps. It’s backed by a subsidiary of BP called Launchpad, a venture capital-like group that funds low-carbon startups which might one day become billion-dollar companies—”unicorns” in startup lingo.

VYVE is still testing out new features, but thousands of people in the United Kingdom and United States are already using it, said Mike Capper, the company’s founder. Older carbon calculators required you to check last month’s energy bill or remember what you ate for lunch on Tuesday. VYVE keeps things simple by focusing on emissions from transportation. Capper, who has worked on efforts to reduce emissions in BP’s supply chain, envisions a future where VYVE is on smartphones around the world. “I want to be the leading organization that people turn to track their carbon footprint and reduce it,” he said.

The “carbon footprint” concept is everywhere these days, as a range of big corporations pledge to slash their carbon emissions to tackle global warming. Amazon plans to get to “net-zero” emissions by 2040, Microsoft vowed to go “carbon negative” by 2030, and Lyft plans to have an entirely electric fleet of vehicles by 2030.

The corporate promises are new, but the conversation about our personal carbon emissions has been around for decades. Environmentalists have long obsessed over the emissions associated with their lifestyle decisions—whether to fly, own a car, and eat red meat. It’s a concept made popular by—get this—BP itself. More than 20 years ago, one of the company’s marketing campaigns helped cement the perception that the responsibility for reducing emissions lay with individuals, working the phrase “carbon footprint” onto our tongues. The underlying message: Let’s talk about how to solve your emissions problems.

You might think that a company evangelizing the carbon footprint would have its own house in order. But research shows that since the late 1980s, just 100 big companies—including BP—are responsible for about 70 percent of global emissions. BP is near the top of the list of the highest-emitting companies in the world, responsible for more than 34 billion metric tons of carbon emissions since 1965.

The oil giant is now reckoning with—or at least acknowledging—that legacy. In recent years, the company’s direct greenhouse gas emissions have started to dip, though they rose in 2019 after some major acquisitions. BP’s new CEO, Bernard Looney, admitted in an interview with the Sunday Times earlier this month that his work is “socially challenging,” saying that some BP employees were becoming disillusioned with the company’s role in contributing to pollution. He added that he understands the view that oil “is a bad industry.”

BP has recently made some big promises, announcing this month that it would produce 40 percent less oil and gas within a decade, as part of a shift in strategy to broaden its range of energy sources. And it’s doubled down on the carbon footprint. Last October, BP tweeted a link to a different calculator it had created, saying: “The first step to reducing your emissions is to know where you stand. Find out your #carbonfootprint with our new calculator & share your pledge today!”

Funding projects like VYVE in tandem with carbon-cutting promises could be viewed as part of a larger, earnest effort to take on climate change. Of course, a skeptic might see it as another example of “greenwashing,” a type of PR spin that looks good on the surface, but only serves to hide the muck underneath.

One such skeptic is the inventor of the “ecological footprint” idea, William Rees, an emeritus professor of ecology at the University of British Columbia. Rees doubts that companies will do what it takes to avoid disastrous climate change. “It may sound cynical,” he said, “but mainstream governments and the corporate sector really have no interest in making the fundamental structural changes needed for the economy to become ‘sustainable.'” That kind of transformation would mean overhauling businesses for the sake of the planet at the expense of profits.

Capper, VYVE’s founder, thinks the scale of the problem posed by climate change means governments, businesses, and individuals all need to take action. The capacity of individual action is untapped, he said, since “99 percent” of the population doesn’t know what their footprint is, let alone know how to reduce it. “People haven’t got a clue,” he told Grist.

Social scientists have long argued that ditching plastic straws, bringing reusable bags to the grocery store, and other small steps could be a gateway to getting politically involved. The thinking is that the more people recycle, the more likely they are to identify as environmentalists, the type of folks who would join the Sierra Club or a get-out-the-vote campaign in a community overburdened by pollution. There’s also evidence that green habits are contagious; if you get solar panels and drive an electric car, your neighbors are more likely to do the same, thanks to peer pressure.

The narrative of individual action rose to prominence in 1990, after years of weakened protections for the environment under the Reagan administration. It gave environmentalists a sense of agency when they’d given up on policy.

Recent research, however, suggests that engaging in environmentally-friendly lifestyle behaviors can sometimes backfire. It might lead you to think you’ve already done enough by taking plastic bottles to the recycling center last week. Looking at your own footprint could also distract you from paying attention to the much bigger polluters out there.

Experts caution that tracking your carbon footprint with an app like VYVE might play into that trap. Julie Doyle, a professor of media and communication at the University of Brighton, said in an email that VYVE appeared to focus on “individual behaviour rather than the systemic and structural changes required for addressing climate change—particularly as it encourages individual financial payment to carbon reduction projects.”

This year, we got a taste of how far individual action might get us. As coronavirus spread across the world, the ensuing lockdowns meant that a lot fewer people were flying around and driving their gas-guzzling cars. The drop in transportation activity led to a dip in carbon emissions, at least for a spell: The Global Carbon Project estimates that the lockdowns will put a 4 to 7 percent dent in global emissions this year. Not bad, right?

Well, one recent analysis called the overall effect “negligible.” In order to keep global warming to 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) above pre-industrial levels, we’d need to see a 7 to 8 percent cut in emissions year after year, Rees said. In other words, eliminating transportation wouldn’t get us very far—20 percent of the way there, tops. The other 80 percent of emissions come from electricity, heating, agriculture, manufacturing, and other types of industry. Even if we were trapped in permanent lockdown, that still wouldn’t get us close to solving climate change.

On a hot summer day in the early 1950s, Rees, around 10 years old at the time, was eating a feast at his grandparents’ farm. Staring absently at the beef, chicken, potatoes, and baby carrots on his plate, Rees had a realization: He had helped raise all of it. “I knew deep in my bones that farm work and food made me a product of soil and land,” he wrote in a reflection later on.

That moment led him to study, and later teach, ecology. His work at the University of British Columbia has focused on ecological economics and the limits of the land to provide for humanity’s needs. It wasn’t a popular line of research among his academic colleagues, who argued that with people congregated in cities and towns, the Earth was still mostly empty. Rees thought differently. “That’s just where we keep our bodies,” he said. “The land we use in cities is not in the city, it’s everywhere else.”

In the early 1990s, Rees was writing a paper on this subject when his computer crashed. His new one took up less area on his desk, so it had a smaller “footprint” — and that’s when the lightbulb turned on. In a much-cited 1992 paper, Rees coined the term “ecological footprint,” a measure by which people could understand how any population—an individual, a city, a country—was affecting the planet. For climate change specifically, “carbon footprint” was the next logical step.

You could say the rest was history, or you could say it was BP’s turn. In 2000, BP launched an award-winning ad campaign with the assistance of the public relations agency Ogilvy & Mather. The goal was to rebrand BP as an environmentally-friendly company. “British Petroleum” was out, “Beyond Petroleum” was in.

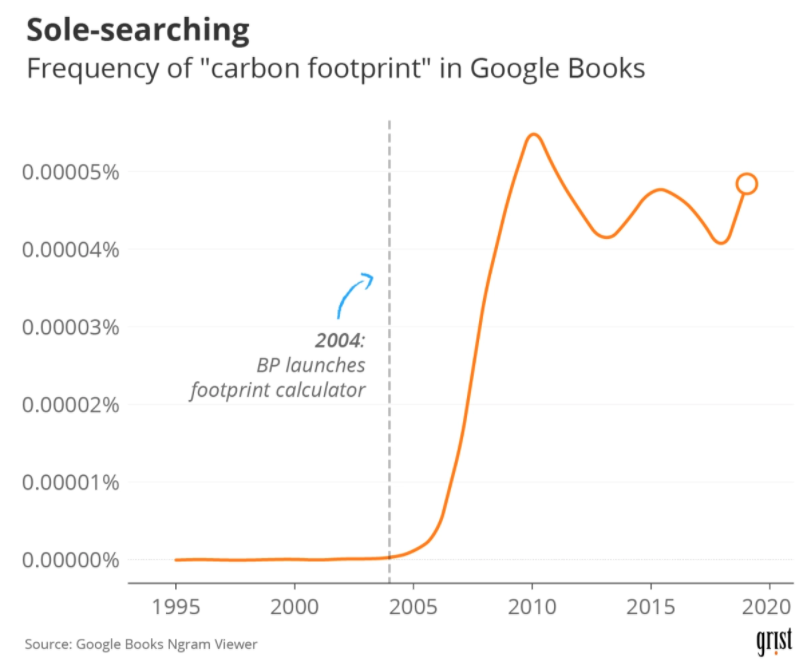

In 2004, BP unveiled a carbon footprint calculator, and the following year, it released a series of advertisements asking questions such as “What on earth is a carbon footprint?” and “What size is your carbon footprint?” Mathis Wackernagel, a colleague of Rees and the president of the Global Footprint Network, later told a reporter that BP’s backing gave the term its “biggest boost.” According to Google Ngram, a tool that tracks the usage of words in books over time, the phrase soared in popularity after BP’s marketing campaign.

The idea of the footprint took off, but not in the way Rees had hoped. By his definition, a footprint is physical; it’s the amount of land area required to support someone’s lifestyle, a measure with finite limits. “When industry talks about carbon footprints, they just talk about the weight of carbon being emitted each year,” Rees said. “If 37 billion tons of CO2 goes up into the atmosphere—well, what does that mean?” Without a point of reference as to what amount of carbon dioxide the world can sequester, “it doesn’t mean anything.”

In a recent article on the news website Mashable, some communication experts denounced the phrase “carbon footprint” as fossil fuel “propaganda.” The emphasis on personal responsibility, they argued, subtly shifts the burden of climate change from governments and corporations to individuals.

BP’s ads in the 2000s echoed the earlier marketing campaigns. Consider the famous “Crying Indian” ad from the 1970s, in which a Native American man sheds a tear after someone passing by in a car throws trash at his moccasins. “People start pollution,” the narrator says. “People can stop it.” Turns out that the group behind the anti-litter PSA, Keep America Beautiful, was funded by Coca-Cola and Dixie, maker of the Dixie Cup, the very same companies making all the trash scattered on the road.

“Corporate America in general has always tried to, with the help of all kinds of other actors, put the onus of environmental protection in general and dealing with climate change on individuals,” said Riley Dunlap, a professor of sociology at Oklahoma State University. In the United States, a country with a strong streak of individualism and belief in the Protestant work ethic, people were more likely to accept this narrative of personal responsibility for a society-wide problem.

The story that individual choices could save us has been repeated so many times that the idea often passes without discussion and plays an outsized role in policy discussions and company decisions. “I’m not trying to impugn the motives of some of the people working for VYVE,” Dunlap said of the personal emissions-tracking app. “But they’ve bought into this thing, too. BP and others have convinced them that individuals are the key thing, or else they wouldn’t be working on this.”

Once you’ve logged your first trip with VYVE, a message comes up on the bottom of your screen. “CONGRATULATIONS,” it says. “You just took another step to understanding your impact.”

Capper, the founder of VYVE, said he was unaware of BP’s history of promoting the carbon footprint. “I absolutely believe BP’s on the right path with the commitments it’s made and the actions the organization is taking,” he said. “I have a lot of pride in that, actually.”

In response to questions about whether VYVE’s focus on individuals could let companies off the hook, David Nicholas, a spokesperson for BP, pointed to the company’s new carbon-cutting goals as an example of its sincerity. Within a decade, he said, it’s likely that BP’s investment in low-carbon energy will increase 10-fold, with “oil and gas production falling by a million barrels a day, or 40 percent.” Carbon offsets will play a role in helping both businesses and VYVE users reach net-zero emissions, he added, and the app would help people do that through “gold-standard offsetting projects,” as measured by United Nations guidelines.

Although the website of Launchpad, BP’s “unicorn factory” that’s backing VYVE, says it aims to “accelerate the energy transition,” some of the companies it supports appear to be tied to fossil fuel production. Take Stryde, a company that maps rock formations below Earth’s surface to help explore for more oil. Stryde’s website says that its heritage “is firmly in oil and gas” and that unlocking oil and gas fields “lies at the core of our offer.” The company is investigating how its technology could be used for carbon sequestration, mining, and renewables.

Tom Burke, the chair of environmental think tank E3G and a former adviser to BP, doesn’t think there’s any hidden political strategy behind VYVE. Rather, he suspects that the app might have simply been borne out of a desire to do some good, perhaps driven by younger BP staff.

Given the lack of public trust in the oil industry, Burke suggested that VYVE be more transparent by, for example, posting on its website a list of who on its board of directors works for BP. “If they don’t make it absolutely clear that they are the major player in this, then it undermines confidence in it,” Burke said of BP. That wouldn’t change the fact that “offsetting is really problematic,” he said. Carbon offset projects have earned a shaky reputation for not always working out as planned.

Despite decades of talking about carbon footprints and “feel-good carbon offsetting,” the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere keeps rising, Rees said.

“Individuals are really almost powerless to do anything,” Rees said. “You can change your purchasing habits a little, but on the whole what we do as individuals is relatively trivial, because the heavy lifting — the kinds of things that would make a real difference — are actions taken for the common good.”

So is it time to forget about your carbon footprint? Rees thinks the idea can still be useful, though it would help if the climate movement reclaimed the concept and took it out of the hands of oil companies.

“Look, what’s the alternative here?” Rees asked. “Stop talking about the carbon emissions altogether?”