This story is adapted from Perilous Bounty copyright © 2020. Published by Bloomsbury USA.

In November 1860, a young scientist from upstate New York named William Brewer disembarked in San Francisco after a long journey that took him from New York City through Panama and then north along the Pacific coast. “The weather is perfectly heavenly,” he enthused in a letter to his brother back east. The fast-growing metropolis was already revealing the charms we know today: “large streets, magnificent buildings,” adorned by “many flowers we [northeasterners] see only in house cultivations: various kinds of geraniums growing of immense size, dew plant growing like a weed, acacia, fuchsia, etc. growing in the open air.”

Flowery prose aside, Brewer was on a serious mission. Barely a decade after being claimed as a US state, California was plunged in an economic crisis. The gold rush had gone bust, and thousands of restive settlers were left scurrying about, hot after the next ever-elusive mineral bonanza. The fledgling legislature had seen fit to hire a state geographer to gauge the mineral wealth underneath its vast and varied terrain, hoping to organize and rationalize the mad lunge for buried treasure. The potential for boosting agriculture as a hedge against mining wasn’t lost on the state’s leaders. They called on the state geographer to deliver a “full and scientific description of the state’s rocks, fossils, soils, and minerals, and its botanical and zoological productions, together with specimens of same.”

The task of completing the fieldwork fell to the 32-year-old Brewer, a Yale-trained botanist who had studied cutting-edge agricultural science in Europe. His letters home, chronicling his four-year journey up and down California, form one of the most vivid contemporary accounts of its early statehood.

They also provide a stark look at the greatest natural disaster known to have befallen the western United States since European contact in the 16th century: the Great Flood of 1861–1862. The cataclysm cut off telegraph communication with the East Coast, swamped the state’s new capital, and submerged the entire Central Valley under as much as 15 feet of water. Yet in modern-day California—a region that author Mike Davis once likened to a “Book of the Apocalypse theme park,” where this year’s wildfires have already burned 1.4 million acres, and dozens of fires are still raging—the nearly forgotten biblical-scale flood documented by Brewer’s letters has largely vanished from the public imagination, replaced largely by traumatic memories of more recent earthquakes.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

When it was thought of at all, the flood was once considered a thousand-year anomaly, a freak occurrence. But emerging science demonstrates that floods of even greater magnitude occurred every 100 to 200 years in California’s precolonial history. Climate change will make them more frequent still. In other words, the Great Flood was a preview of what scientists expect to see again, and soon. And this time, given California’s emergence as agricultural and economic powerhouse, the effects will be all the more devastating.

Barely a year after Brewer’s sunny initial descent from a ship in San Francisco Bay, he was back in the city, on a break. In a November 1861 letter home, he complained of a “week of rain.” In his next letter, two months later, Brewer reported jaw-dropping news: Rain had fallen almost continuously since he had last written—and now the entire Central Valley was underwater. “Thousands of farms are entirely underwater—cattle starving and drowning.”

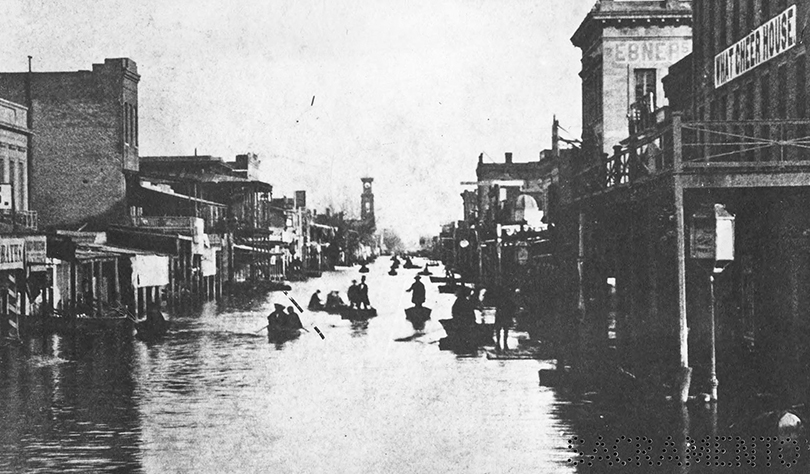

Picking up the letter nine days later, he wrote that a bad situation had deteriorated. All the roads in the middle of the state are “impassable, so all mails are cut off.” Telegraph service, which had only recently been connected to the East Coast through the Central Valley, stalled. “The tops of the poles are under water!” The young state’s capital city, Sacramento, about 100 miles northeast of San Francisco at the western edge of the valley and the intersection of two rivers, was submerged, forcing the legislature to evacuate—and delaying a payment Brewer needed to forge ahead with his expedition.

The surveyor gaped at the sheer volume of rain. In a normal year, Brewer reported, San Francisco received about 20 inches. In the 10 weeks leading up to January 18, 1862, the city got “thirty-two and three-quarters inches and it is still raining!”

Stereoscope photo of J Street in Sacrament during the 1862 flood.

Charles L. Weed/California State Library

Brewer went on to recount scenes from the Central Valley that would fit in a Hollywood disaster epic. “An old acquaintance, a buccaro [cowboy], came down from a ranch that was overflowed,” he wrote. “The floor of their one-story house was six weeks under water before the house went to pieces.” Steamboats “ran back over the ranches fourteen miles from the [Sacramento] river, carrying stock [cattle], etc., to the hills,” he reported. He marveled at the massive impromptu lake made up of “water ice cold and muddy,” in which “winds made high waves which beat the farm homes in pieces.” As a result, “every house and farm over this immense region is gone.”

Eventually, in March, Brewer made it to Sacramento, hoping (without success) to lay hands on the state funds he needed to continue his survey. He found a city still in ruins, weeks after the worst of the rains. “Such a desolate scene I hope never to see again,” he wrote: “Most of the city is still under water, and has been for three months…Every low place is full—cellars and yards are full, houses and walls wet, everything uncomfortable.” The “better class of houses” were in rough shape, Brewer observed, but “it is with the poorer classes that this is the worst.” He went on: “Many of the one-story houses are entirely uninhabitable; others, where the floors are above the water are, at best, most wretched places in which to live.” He summarized the scene:

Many houses have partially toppled over; some have been carried from their foundations, several streets (now avenues of water) are blocked up with houses that have floated in them, dead animals lie about here and there—a dreadful picture. I don’t think the city will ever rise from the shock, I don’t see how it can.

Brewer’s account is important for more than just historical interest. In the 160 years since the botanist set foot on the West Coast, California has transformed from an agricultural backwater to one of the jewels of the US food system. The state produces nearly all of the almonds, walnuts, and pistachios consumed domestically; 90 percent or more of the broccoli, carrots, garlic, celery, grapes, tangerines, plums, and artichokes; at least 75 percent of the cauliflower, apricots, lemons, strawberries, and raspberries; and more than 40 percent of the lettuce, cabbage, oranges, peaches, and peppers.

And as if that weren’t enough, California is also a national hub for milk production. Tucked in amid the almond groves and vegetable fields are vast dairy operations that confine cows together by the thousands and produce more than a fifth of the nation’s milk supply, more than any other state. It all amounts to a food-production juggernaut: California generates $46 billion worth of food per year, nearly double the haul of its closest competitor among US states, the corn-and-soybean behemoth Iowa.

You’ve probably heard that ever-more frequent and severe droughts threaten the bounty we’ve come to rely on from California. Water scarcity, it turns out, isn’t the only menace that stalks California valleys that stock our supermarkets. The opposite—catastrophic flooding—also occupies a niche in what Mike Davis, the great chronicler of Southern California’s sociopolitical geography, has called the state’s “ecology of fear.” Indeed, his classic book of that title opens with an account of a 1995 deluge that saw “million-dollar homes tobogganed off their hill-slope perches” and small children and pets “sucked into the deadly vortices of the flood channels.”

Yet floods tend to be less feared than rival horsemen of the apocalypse in the state’s oft-stimulated imagination of disaster. The epochal 2011–2017 drought, with its missing-in-action snowpacks and draconian water restrictions, burned itself into the state’s consciousness. Californians are rightly terrified of fires like the ones that roared through the northern Sierra Nevada foothills and coastal canyons near Los Angeles in the fall of 2018, killing nearly 100 people and fouling air for miles around, or the current LNU Lightning Complex fire that has destroyed nearly 1,000 structures and killed five people in the region between Sacramento and San Francisco. Many people are frightfully aware that a warming climate will make such conflagrations increasingly frequent. And “earthquake kits” are common gear in closets and garages all along the San Andreas Fault, where the next Big One lurks. Floods, though they occur as often in Southern and Central California as they do anywhere in the United States, don’t generate quite the same buzz.

But a growing body of research shows there’s a flip side to the megadroughts Central Valley farmers face: megafloods. The region most vulnerable to such a water-drenched cataclysm in the near future is, ironically enough, the California’s great arid, sinking food production basin, the beleaguered behemoth of the US food system: the Central Valley. Bordered on all sides by mountains, the Central Valley stretches 450 miles long, is on average 50 miles wide, and occupies a land mass of 18,000 square miles, or 11.5 million acres—roughly equivalent in size to Massachusetts and Vermont combined. Wedged between the Sierra Nevada to the east and the Coast Ranges to the west, it’s one of the globe’s greatest expanses of fertile soil and temperate weather. For most Americans, it’s easy to ignore the Central Valley, even though it’s as important to eaters as Hollywood is to moviegoers or Silicon Valley is to smartphone users. Occupying less than 1 percent of US farmland, the Central Valley churns out a quarter of the nation’s food supply.

At the time of the Great Flood, the Central Valley was still mainly cattle ranches, the farming boom a ways off. Late in 1861, the state suddenly emerged from a two-decade dry spell when monster storms began lashing the west coast from Baja California to present-day Washington State. In central California, the deluge initially took the form of 10 to 15 feet of snow dumped onto the Sierra Nevada, according to research by the UC Berkeley paleoclimatologist B. Lynn Ingram and laid out in her 2015 book, The West Without Water, co-written with Frances Malamud-Roam. Ingram has emerged as a kind of Cassandra of drought and flood risks in the western United States. Soon after the blizzards came days of warm, heavy rain, which in turn melted the enormous snowpack. The resulting slurry cascaded through the Central Valley’s network of untamed rivers.

As floodwater gathered in the valley, it formed a vast, muddy, wind-roiled lake, its size “rivaling that of Lake Superior,” covering the entire Central Valley floor, from the southern slopes of the Cascade Mountains near the Oregon border to the Tehachapis, south of Bakersfield, with depths in some places exceeding 15 feet.

At least some of the region’s remnant indigenous population saw the epic flood coming and took precautions to escape devastation, Ingram reports, quoting an item in the Nevada City Democrat on January 11, 1862:

We are informed that the Indians living in the vicinity of Marysville left their abodes a week or more ago for the foothills predicting an unprecedented overflow. They told the whites that the water would be higher than it has been for thirty years, and pointed high up on the trees and houses where it would come. The valley Indians have traditions that the water occasionally rises 15 or 20 feet higher than it has been at any time since the country was settled by whites, and as they live in the open air and watch closely all the weather indications, it is not improbable that they may have better means than the whites of anticipating a great storm.

All in all, thousands of people died, “one-third of the state’s property was destroyed, and one home in eight was destroyed completely or carried away by the floodwaters.” As for farming, the 1862 megaflood transformed valley agriculture, playing a decisive role in creating today’s Anglo-dominated, crop-oriented agricultural powerhouse: a 19th-century example of the “disaster capitalism” that Naomi Klein describes in her 2007 book, The Shock Doctrine.

Prior to the event, valley land was still largely owned by Mexican rancheros who held titles dating to Spanish rule. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which triggered California’s transfer from Mexican to US control, gave rancheros US citizenship and obligated the new government to honor their land titles. The treaty terms met with vigorous resentment from white settlers eager to shift from gold mining to growing food for the new state’s burgeoning cities. The rancheros thrived during the gold rush, finding a booming market for beef in mining towns. By 1856, their fortunes had shifted. A severe drought that year cut production, competition from emerging US settler ranchers meant lower prices, and punishing property taxes—imposed by land-poor settler politicians—caused a further squeeze. “As a result, rancheros began to lose their herds, their land, and their homes,” writes the historian Lawrence James Jelinek.

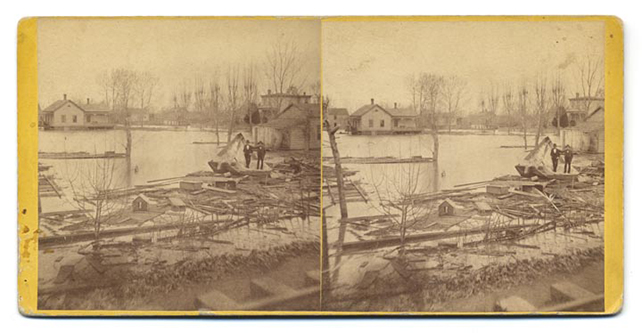

Stereoscope photo showing destruction from the flood in Sacramento.

Gove & Allen/California State Library

The devastation of the 1862 flood, its effects magnified by a brutal drought that started immediately afterward and lasted through 1864, “delivered the final blow,” Jelinek writes. Between 1860 and 1870, California’s cattle herd, concentrated in the valley, plunged from 3 million to 630,000. The rancheros were forced to sell their land to white settlers at pennies per acre, and by 1870, “many rancheros had become day laborers in the towns,” Jelinek reports. The valley’s emerging class of settler farmers quickly turned to wheat and horticultural production, and set about harnessing and exploiting the region’s water resources, both those gushing forth from the Sierra Nevada and those beneath their feet.

Despite all the trauma it generated and the agricultural transformation it cemented in the Central Valley, the flood quickly faded from memory in California and the broader United States. To his shocked assessment of a still-flooded and supine Sacramento months after the storm, Brewer added a prophetic coda:

No people can so stand calamity as this people. They are used to it. Everyone is familiar with the history of fortunes quickly made and as quickly lost. It seems here more than elsewhere the natural order of things. I might say, indeed, that the recklessness of the state blunts the keener feelings and takes the edge from this calamity.

Indeed, the new state’s residents ended up shaking off the cataclysm. What lesson does the Great Flood of 1862 hold for today? The question is important. Back then, just around 500,000 people lived in the entire state, and the Central Valley was a sparsely populated badland. Today, the valley has a population of 6.5 million people and boasts the state’s three fastest-growing counties. Sacramento (population 501,344), Fresno (538,330), and Bakersfield (386,839) are all budding metropolises. The state’s long-awaited high-speed train, if it’s ever completed, will place Fresno residents within an hour of Silicon Valley, driving up its appeal as a bedroom community.

In addition to the potentially vast human toll, there’s also the fact that the Central Valley has emerged as a major linchpin of the US and global food system. Could it really be submerged under fifteen feet of water again—and what would that mean?

In less than two centuries as a US state, California has maintained its reputation as a sunny paradise while also enduring the nation’s most erratic climate: the occasional massive winter storm roaring in from the Pacific; years-long droughts. But recent investigations into the fossil record show that these past years have been relatively stable.

One avenue of this research is the study of the regular megadroughts, the most recent of which occurred just a century before Europeans made landfall on the North American west coast. As we are now learning, those decades-long arid stretches were just as regularly interrupted by enormous storms—many even grander than the one that began in December 1861. (Indeed, that event itself was directly preceded and followed by serious droughts.) In other words, the same patterns that make California vulnerable to droughts also make it ripe for floods.

Beginning in the 1980s, scientists including B. Lynn Ingram began examining streams and banks in the enormous delta network that together serve as the bathtub drain through which most Central Valley runoff has flowed for millennia, reaching the ocean at the San Francisco Bay. (Now-vanished Tulare Lake gathered runoff in the southern part of the valley.) They took deep-core samples from river bottoms, because big storms that overflow the delta’s banks transfer loads of soil and silt from the Sierra Nevada and deposit a portion of it in the Delta. They also looked at fluctuations in old plant material buried in the sediment layers. Plant species that thrive in freshwater suggest wet periods, as heavy runoff from the mountains crowds out seawater. Salt-tolerant species denote dry spells, as sparse mountain runoff allows seawater to work into the delta.

What they found was stunning. The Great Flood of 1862 was no one-off black-swan event. Summarizing the science, Ingram and USGS researcher Michael Dettinger deliver the dire news: A flood comparable to—and sometimes much more intense than—the 1861–1862 catastrophe occurred sometime between 1235–1360, 1395–1410, 1555–1615, 1750–1770, and 1810–1820; “that is, one megaflood every 100 to 200 years.” They also discovered that the 1862 flood didn’t appear in the sediment record in some sites that showed evidence of multiple massive events—suggesting that it was actually smaller than many of the floods that have inundated California over the centuries.

During its time as a US food-production powerhouse, California has been known for its periodic droughts and storms. But Ingram and Dettinger’s work pulls the lens back to view the broader timescale, revealing the region’s swings between megadroughts and megastorms—ones more than severe enough to challenge concentrated food production, much less dense population centers.

The dynamics of these storms themselves explain why the state is also prone to such swings. Meteorologists have known for decades that those tempests that descend upon California over the winter—and from which the state receives the great bulk of its annual precipitation—carry moisture from the South Pacific. In the late 1990s, scientists discovered that these “pineapple expresses,” as TV weather presenters call them, are a subset of a global weather phenomenon: long, wind-driven plumes of vapor about a mile above the sea that carry moisture from warm areas near the equator on a northeasterly path to colder, drier regions toward the poles. They carry so much moisture—often more than twenty-five times the flow of the Mississippi River, over thousands of miles—that they’ve been dubbed “atmospheric rivers.”

In a pioneering 1998 paper, researchers Yong Zhu and Reginald E. Newell found that nearly all the vapor transport between the subtropics (regions just south or north of the equator, depending on the hemisphere) toward the poles occurred in just five or six narrow bands. And California, it turns out, is the prime spot in the western side of the northern hemisphere for catching them at full force during the winter months.

As Ingram and Dettinger note, atmospheric rivers are the primary vector for California’s floods. That includes pre-Columbian cataclysms as well as the Great Flood of 1862, all the way to the various smaller ones that regularly run through the state. Between 1950 and 2010, Ingram and Dettinger write, atmospheric rivers “caused more than 80 percent of flooding in California rivers and 81 percent of the 128 most well-documented levee breaks in California’s Central Valley.”

Paradoxically, they are at least as much a lifeblood as a curse. Between eight and 11 atmospheric rivers hit California every year, the great majority of them doing no major damage, and they deliver between 30 and 50 percent of the state’s rain and snow. But the big ones are damaging indeed. Other researchers are reaching similar conclusions. In a study released in December 2019, a team from the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that atmospheric-river storms accounted for 84 percent of insured flood damages in the western United States between 1978 and 2017; the 13 biggest storms wrought more than half the damage.

So the state—and a substantial portion of our food system—exists on a razor’s edge between droughts and floods, its annual water resources decided by massive, increasingly fickle transfers of moisture from the South Pacific. As Dettinger puts it, the “largest storms in California’s precipitation regime not only typically end the state’s frequent droughts, but their fluctuations also cause those droughts in the first place.”

We know that before human civilization began spewing millions of tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere annually, California was due “one megaflood every 100 to 200 years”—and the last one hit more than a century and a half ago. What happens to this outlook when you heat up the atmosphere by 1 degree Celsius—and are on track to hit at least another half-degree Celsius increase by midcentury?

That was the question posed by Daniel Swain and a team of researchers at UCLA’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences in a series of studies, the first of which was published in 2018. They took California’s long pattern of droughts and floods and mapped it onto the climate models based on data specific to the region, looking out to century’s end.

What they found isn’t comforting. As the tropical Pacific Ocean and the atmosphere just above it warm, more seawater evaporates, feeding ever bigger atmospheric rivers gushing toward the California coast. As a result, the potential for storms on the scale of the ones that triggered the Great Flood has increased “more than threefold,” they found. So an event expected to happen on average every 200 years will now happen every 65 or so. It is “more likely than not we will see one by 2060,” and it could plausibly happen again before century’s end, they concluded.

As the risk of a catastrophic event increases, so will the frequency of what they call “precipitation whiplash”: extremely wet seasons interrupted by extremely dry ones, and vice versa. The winter of 2016–2017 provides a template. That year, a series of atmospheric-river storms filled reservoirs and at one point threatened a major flood in the northern Central Valley, abruptly ending the worst multiyear drought in the state’s recorded history.

Swings on that magnitude normally occur a handful of times each century, but in the model by Swain’s team, “it goes from something that happens maybe once in a generation to something that happens two or three times,” he told me in an interview. “Setting aside a repeat of 1862, these less intense events could still seriously test the limits of our water infrastructure.” Like other efforts to map climate change onto California’s weather, this one found that drought years characterized by low winter precipitation would likely increase—in this case, by a factor of as much as two, compared with mid-20th-century patterns. But extreme-wet winter seasons, accumulating at least as much precipitation as 2016–2017, will grow even more: they could be three times as common as they were before the atmosphere began its current warming trend.

While lots of very wet years—at least the ones that don’t reach 1861–1862 levels—might sound encouraging for food production in the Central Valley, there’s a catch, Swain said. His study looked purely at precipitation, independent of whether it fell as rain or snow. A growing body of research suggests that as the climate warms, California’s precipitation mix will shift significantly in favor of rain over snow. That’s dire news for our food system, because the Central Valley’s vast irrigation networks are geared to channeling the slow, predictable melt of the snowpack into usable water for farms. Water that falls as rain is much harder to capture and bend to the slow-release needs of agriculture.

In short, California’s climate, chaotic under normal conditions, is about to get weirder and wilder. Indeed, it’s already happening.

What if an 1862-level flood, which is overdue and “more likely than not” to occur with a couple of decades, were to hit present-day California?

Starting in 2008, the USGS set out to answer just that question, launching a project called the ARkStorm (for “atmospheric river 1,000 storm”) Scenario. The effort was modeled on a previous USGS push to get a grip on another looming California cataclysm: a massive earthquake along the San Andreas Fault. In 2008, USGS produced the ShakeOut Earthquake Scenario, a “detailed depiction of a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake.” The study “served as the centerpiece of the largest earthquake drill in US history, involving over five thousand emergency responders and the participation of over 5.5 million citizens,” the USGS later reported.

That same year, the agency assembled a team of 117 scientists, engineers, public-policy experts, and insurance experts to model what kind of impact a monster storm event would have on modern California.

At the time, Lucy Jones served as the chief scientist for the USGS’s Multi Hazards Demonstration Project, which oversaw both projects. A seismologist by training, Jones spent her time studying the devastations of earthquakes and convincing policy makers to invest resources into preparing for them. The ARkStorm project took her aback, she told me. The first thing she and her team did was ask, What’s the biggest flood in California we know about? “I’m a fourth-generation Californian who studies disaster risk, and I had never heard of the Great Flood of 1862,” she said. “None of us had heard of it,” she added—not even the meteorologists knew about what’s “by far the biggest disaster ever in California and the whole Southwest” over the past two centuries.

At first, the meteorologists were constrained in modeling a realistic megastorm by a lack of data; solid rainfall-gauge measures go back only a century. But after hearing about the 1862 flood, the ARkStorm team dug into research from Ingram and others for information about megastorms before US statehood and European contact. They were shocked to learn that the previous 1,800 years had about six events that were more severe than 1862, along with several more that were roughly of the same magnitude. What they found was that a massive flood is every bit as likely to strike California, and as imminent, as a massive quake.

Even with this information, modeling a massive flood proved more challenging than projecting out a massive earthquake. “We seismologists do this all the time—we create synthetic seismographs,” she said. Want to see what a quake reaching 7.8 on the Richter scale would look like along the San Andreas Fault? Easy, she said. Meteorologists, by contrast, are fixated on accurate prediction of near-future events; “creating a synthetic event wasn’t something they had ever done.” They couldn’t just re-create the 1862 event, because most of the information we have about it is piecemeal, from eyewitness accounts and sediment samples.

To get their heads around how to construct a reasonable approximation of a megastorm, the team’s meteorologists went looking for well-documented 20th-century events that could serve as a model. They settled on two: a series of big storms in 1969 that hit Southern California hardest and a 1986 cluster that did the same to the northern part of the state. To create the ARkStorm scenario, they stitched the two together. Doing so gave the researchers a rich and regionally precise trove of data to sketch out a massive Big One storm scenario.

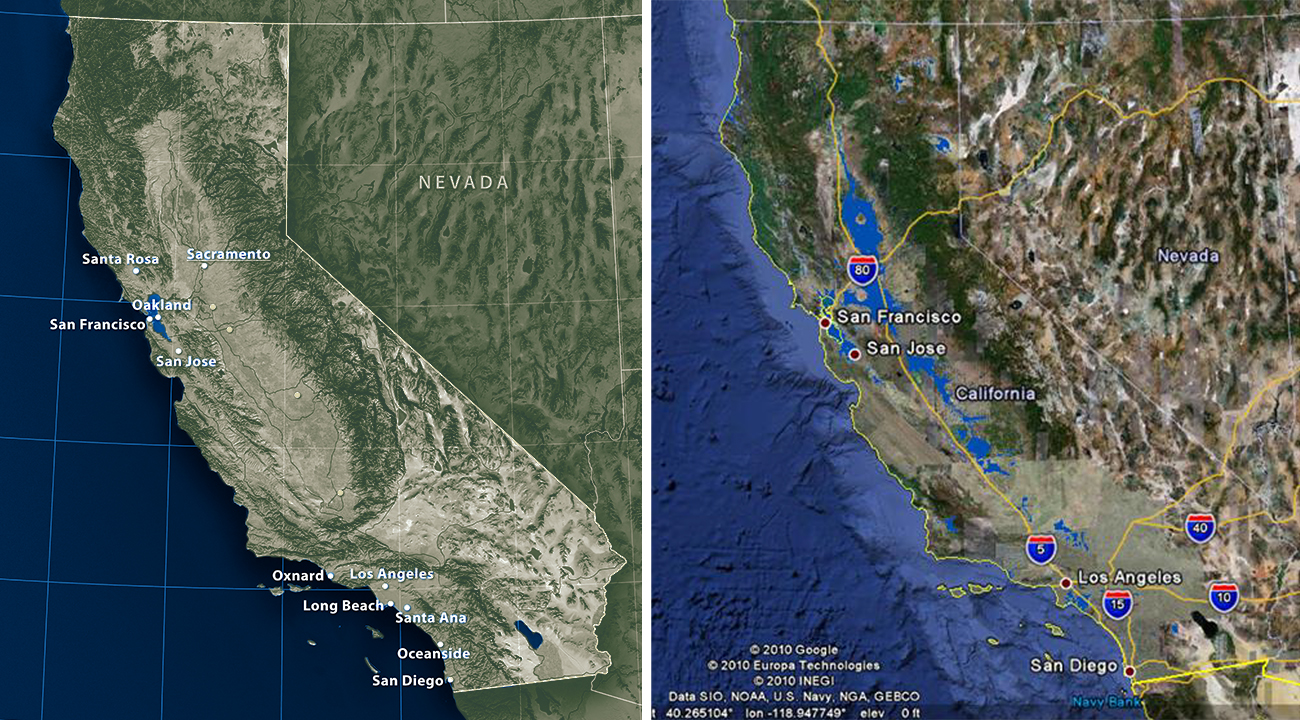

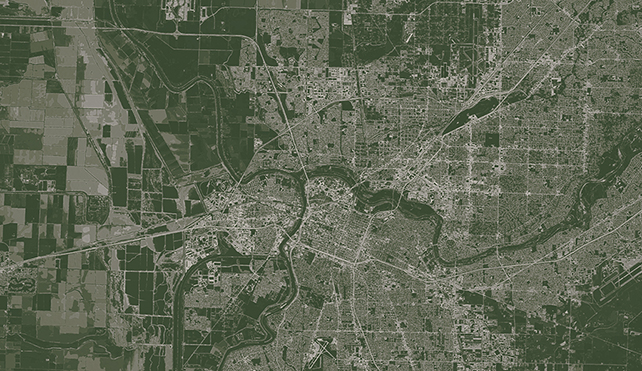

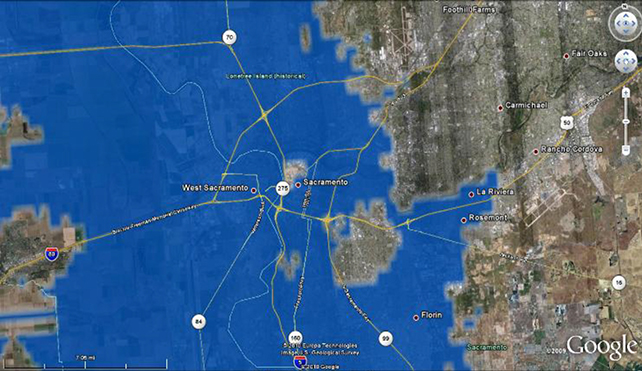

Left, California today. Right, the areas that would be flooded under the ARkStorm Scenario.

Getty; USGS

There was one problem: While the fictional ARkStorm is indeed a massive event, it’s still significantly smaller than the one that caused the Great Flood of 1862. “Our [hypothetical storm] only had total rain for twenty-five days, while there were forty-five days in 1861 to ’62,” Jones said. They plunged ahead anyway, for two reasons. One was that they had robust data on the two twentieth-century storm events, giving disaster modelers plenty to work with. The second was that they figured a smaller-than-1862 catastrophe would help build public buy-in, by making the project hard to dismiss as an unrealistic figment of scaremongering bureaucrats.

What they found stunned them—and should stun anyone who relies on California to produce food (not to mention anyone who lives there). The headline number: $725 billion in damage, nearly four times what the USGS’s seismology team arrived at for its massive-quake scenario ($200 billion). For comparison, the two most costly natural disasters in modern US history—Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Harvey in 2017—racked up $166 billion and $130 billion, respectively. The ARkStorm would “flood thousands of square miles of urban and agricultural land, result in thousands of landslides, [and] disrupt lifelines throughout the state for days or weeks,” the study reckoned. Altogether, 25 percent of the state’s buildings would be damaged.

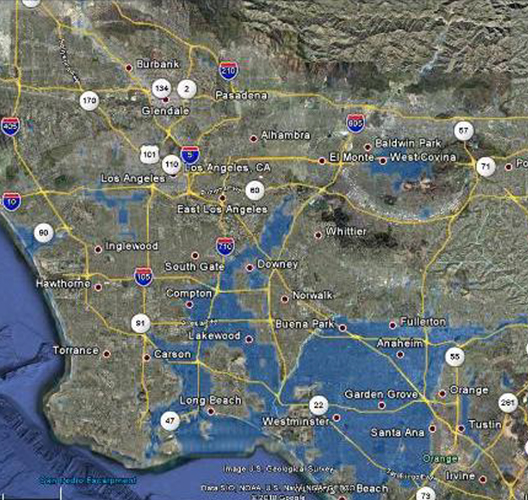

In their model, 25 days of relentless rains overwhelm the Central Valley’s flood-control infrastructure. Then large swaths of the northern part of the Central Valley go under as much as twenty feet of water. The southern part, the San Joaquin Valley, gets off lighter; but a miles-wide band of floodwater collects in the lowest-elevation regions, ballooning out to encompass the expanse that was once the Tulare Lake bottom and stretching to the valley’s southern extreme. Most metropolitan parts of the Bay Area escape severe damage, but swaths of Los Angeles and Orange Counties experience “extensive flooding.”

Los Angeles flooding in the ARkStorm Scenario

USGS Open-File Report

As Jones stressed to me in our conversation, the ARkStorm scenario is a cautious approximation; a megastorm that matches 1862 or its relatively recent antecedents could plausibly bury the entire Central Valley underwater, northern tip to southern. As the report puts it: “Six megastorms that were more severe than 1861–1862 have occurred in California during the last 1800 years, and there is no reason to believe similar storms won’t occur again.”

A 21st-century megastorm would fall on a region quite different from gold rush–era California. For one thing, it’s much more populous. While the ARkStorm reckoning did not estimate a death toll, it warned of a “substantial loss of life” because “flood depths in some areas could realistically be on the order of 10–20 feet.”

Then there’s the transformation of farming since then. The 1862 storm drowned an estimated 200,000 head of cattle, about a quarter of the state’s entire herd. Today, the Central Valley houses nearly 4 million beef and dairy cows. While cattle continue to be an important part of the region’s farming mix, they no longer dominate it. Today the valley is increasingly given over to intensive almond, pistachio, and grape plantations, representing billions of dollars of investments in crops that take years to establish, are expected to flourish for decades, and could be wiped out by a flood.

Sacramento today

Getty

Apart from economic losses, “the evolution of a modern society creates new risks from natural disasters,” Jones told me. She cited electric power grids, which didn’t exist in mid-19th-century California. A hundred years ago, when electrification was taking off, extended power outages caused inconveniences. Now, loss of electricity can mean death for vulnerable populations (think hospitals, nursing homes, and prisons). Another example is the intensification of farming. When a few hundred thousand cattle roamed the sparsely populated Central Valley in 1861, their drowning posed relatively limited biohazard risks, although, according to one contemporary account, in post-flood Sacramento, there were a “good many drowned hogs and cattle lying around loose in the streets.”

Today, however, several million cows are packed into massive feedlots in the southern Central Valley, their waste often concentrated in open-air liquid manure lagoons, ready to be swept away and blended into a fecal slurry. Low-lying Tulare County houses nearly 500,000 dairy cows, with 258 operations holding on average 1,800 cattle each. Mature modern dairy cows are massive creatures, weighing around 1,500 pounds each and standing nearly 5 feet tall at the front shoulder. Imagine trying to quickly move such beasts by the thousands out of the path of a flood—and the consequences of failing to do so.

A massive flood could severely pollute soil and groundwater in the Central Valley, and not just from rotting livestock carcasses and millions of tons of concentrated manure. In a 2015 paper, a team of USGS researchers tried to sum up the myriad toxic substances that would be stirred up and spread around by massive storms and floods. The cities of 160 years ago could not boast municipal wastewater facilities, which filter pathogens and pollutants in human sewage, nor municipal dumps, which concentrate often-toxic garbage. In the region’s teeming twenty-first-century urban areas, those vital sanitation services would become major threats. The report projects that a toxic soup of “petroleum, mercury, asbestos, persistent organic pollutants, molds, and soil-borne or sewage-borne pathogens” would spread across much of the valley, as would concentrated animal manure, fertilizer, pesticides, and other industrial chemicals.

The valley’s southernmost county, Kern, is a case study in the region’s vulnerabilities. Kern’s farmers lead the entire nation in agricultural output by dollar value, annually producing $7 billion worth of foodstuffs like almonds, grapes, citrus, pistachios, and milk. The county houses more than 156,000 dairy cows in facilities averaging 3,200 head each. That frenzy of agricultural production means loads of chemicals on hand; every year, Kern farmers use around 30 million pounds of pesticides, second only to Fresno among California counties. (Altogether, five San Joaquin Valley counties use about half of the more than 200 million pounds of pesticides applied in California.)

Kern is also one of the nation’s most prodigious oil-producing counties. Its vast array of pump jacks, many of them located in farm fields, produce 70 percent of California’s entire oil output. It’s also home to two large oil refineries. If Kern County were a state, it would be the nation’s seventh-leading oil-producing one, churning out twice as much crude as Louisiana. In a massive storm, floodwaters could pick up a substantial amount of highly toxic petroleum and byproducts. Again, in the ARkStorm scenario, Kern County gets hit hard by rain but mostly escapes the worst flooding. The real “Other Big One” might not be so kind, Jones said.

In the end, the USGS team could not estimate the level of damage that will be visited upon the Central Valley’s soil and groundwater from a megaflood: too many variables, too many toxins and biohazards that could be sucked into the vortex. They concluded that “flood-related environmental contamination impacts are expected to be the most widespread and substantial in lowland areas of the Central Valley, the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, the San Francisco Bay area, and portions of the greater Los Angeles metroplex.”

Jones said the initial reaction to the 2011 release of the ARkStorm report among California’s policymakers and emergency managers was skepticism: “Oh, no, that’s too big—it’s impossible,” they would say. “We got lots of traction with the earthquake scenario, and when we did the big flood, nobody wanted to listen to us,” she said.

But after years of patiently informing the state’s decision makers that such a disaster is just as likely as a megaquake—and likely much more devastating—the word is getting out. She said the ARkStorm message probably helped prepare emergency managers for the severe storms of February 2017. That month, the massive Oroville Dam in the Sierra Nevada foothills very nearly failed, threatening to send a 30-foot-tall wall of water gushing into the northern Central Valley. As the spillway teetered on the edge of collapse, officials ordered the evacuation of 188,000 people in the communities below. The entire California National Guard was put on notice to mobilize if needed—the first such order since the 1992 Rodney King riots in Los Angeles. Although the dam ultimately held up, the Oroville incident illustrates the challenges of moving hundreds of thousands of people out of harm’s way on short notice.

The evacuation order “unleashed a flood of its own, sending tens of thousands of cars simultaneously onto undersize roads, creating hours-long backups that left residents wondering if they would get to high ground before floodwaters overtook them,” the Sacramento Bee reported. Eight hours after the evacuation, highways were still jammed with slow-moving traffic. A California Highway Patrol spokesman summed up the scene for the Bee:

Unprepared citizens who were running out of gas and their vehicles were becoming disabled in the roadway. People were utilizing the shoulder, driving the wrong way. Traffic collisions were occurring. People fearing for their lives, not abiding by the traffic laws. All combined, it created big problems. It ended up pure, mass chaos.

Even so, Jones said the evacuation went as smoothly as could be expected, and likely would have saved thousands of lives if the dam had burst. “But there are some things you can’t prepare for.” Obviously, getting area residents to safety was the first priority, but animal inhabitants were vulnerable, too. If the dam had burst, she said, “I doubt they would have been able to save cattle.”

As the state’s ever-strained emergency-service agencies prepare for the Other Big One, there’s evidence other agencies are struggling to grapple with the likelihood of a megaflood. In the wake of the 2017 near-disaster at Oroville, state agencies spent more than $1 billion repairing the damaged dam and bolstering it for future storms. Just as work was being completed in fall 2018, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission assessed the situation and found that a “probable maximum flood”—on the scale of the ArkStorm—would likely overwhelm the dam. FERC called on the state to invest in a “more robust and resilient design” to prevent a future cataclysm. The state’s Department of Water Resources responded by launching a “needs assessment” of the dam’s safety that’s due to wrap up in 2020.

Of course, in a state beset by the increasing threat of wildfires in populated areas as well as earthquakes, funds for disaster preparation are tightly stretched. All in all, Jones said, “we’re still much more prepared for a quake than a flood.” Then again, it’s hard to conceive of how we could effectively prevent a 21st century repeat of the Great Flood, or how we could fully prepare for the low-lying valley that runs along the center of California like a bathtub—now packed with people, livestock, manure, crops, petrochemicals, and pesticides—to be suddenly transformed into a storm-roiled inland sea.

This story was adapted from Perilous Bounty copyright © 2020. Published by Bloomsbury USA. It’s an unsettling journey into the disaster-haunted regions most responsible for our food supply, with an exploration of possible solutions.