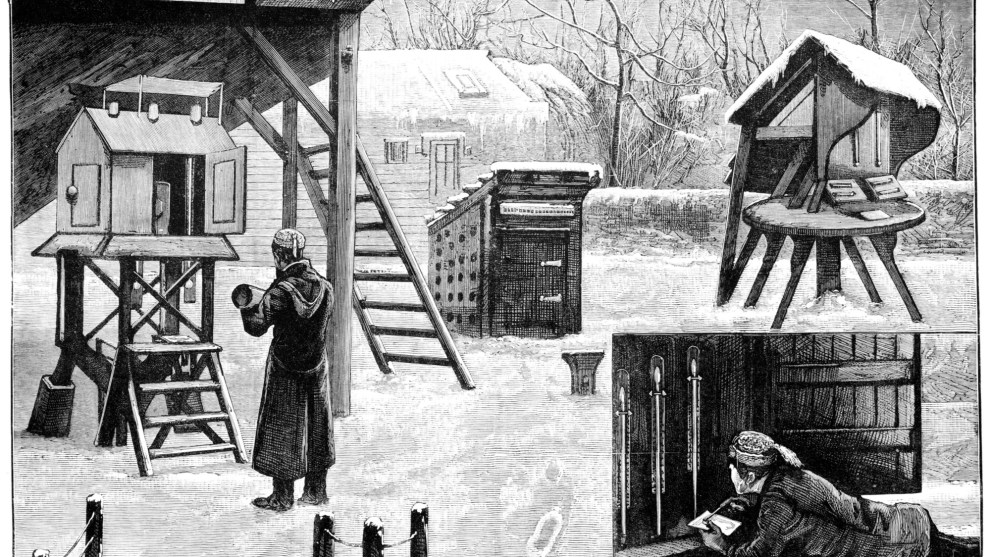

Vintage engraving showing Victorian meteorology.duncan1890/Getty

This story was originally published by Atlas Obscura. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

An incoming cold spell is sending shivers across the American Midwest. Over the next few days, temperatures across the plains and Great Lakes region are forecast to plunge to -30 and -40 degrees Fahrenheit. In Chicago, the high temperature may barely crack double digits. Factoring in the windchill, Minneapolis will feel like a rattling -62 degrees Fahrenheit.

Today, the National Weather Service arrives at these forecasts in a number of ways, including by drawing on satellite imagery to track the movement of polar air. It was a different story in 1903 and 1904, of course, long before satellites beamed images of our planet back down to Earth, and before apps made it easy to call up a weather forecast on your phone. The winter spanning those years was one of the coldest to ever hold Chicago in its grip. Far from the Windy City, and without any sophisticated instruments, a man named “Joe” Harris claimed to see it coming.

Harris was sure that folks were in for a chill. At the end of November 1903, The Inter-Ocean, a Chicago newspaper, rounded up some prognostications from assorted “weather sharps.” To estimate the coming winter’s bite, these men didn’t look to the sky—they looked around them. Harris saw signs of a future freeze in top-heavy turkeys, whose “breast bones of double strength” were “always a sign of cold weather,” the paper reported. Another man saw proof of the coming chill in evergreen trees heavy with extra foliage; others pointed to fish with extra scales, flag stones that “sweat frost every morning,” squirrels stockpiling every nut in sight, and snakes that slithered particularly deep to brumate (a seasonal sluggishness, and their alternative to hibernation). “Turkey bones, rabbit teeth, etc., portend Arctic weather,” the newspaper declared.

It did turn out to be a cold winter, but at least one meteorologist was mighty peeved by the strategy for predicting it. The following December, C. F. von Herrmann, of Raleigh, North Carolina, had had it with the group he dismissed as assorted “groundhog experts, weather sharps, and long range forecasters.” In a report for the U. S. Department of Agriculture, which was then the parent organization of the Weather Bureau, von Herrmann—a section director of the Weather Bureau’s Climate and Crop Service—laid out a plea for people to abandon the “charlatans” who “pretend to believe that they have an infallible system of predicting the weather, storms, floods, or droughts for months or even years ahead, and who foist their predictions upon the public for the benefit of their own pockets.”

The Weather Bureau was still young—the military had been collecting meteorological measurements since 1870, but forecasting only became the duty of a civilian agency in 1890, when Congress shifted the work of gathering meteorological data from the Army’s Signal Service Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce over to the Department of Agriculture. Soon, telegrams were conveying flood warnings, and wireless messages were arriving to ships at sea. Three-day forecasts for the North Atlantic began in 1901, and postal workers delivered day-old forecasts with the mail. The Weather Bureau was trying to build a reputation for getting things right. Accurate, short-term forecasts were one way to build authority; another was taking aim at other types of forecasts and wisdom.

In his report, von Herrmann saw an opportunity to sound a rallying cry for the agency and the field, asking readers to “place their faith in the Weather Bureau, the operation of which cannot fail to be of greater and greater benefit to the people as the science of meteorology advances.”

Harris and von Herrmann may have had different methods, but they’d probably have arrived at the same conclusion: When the mercury drops as low as it will this week, better to make like a snake and hunker down.