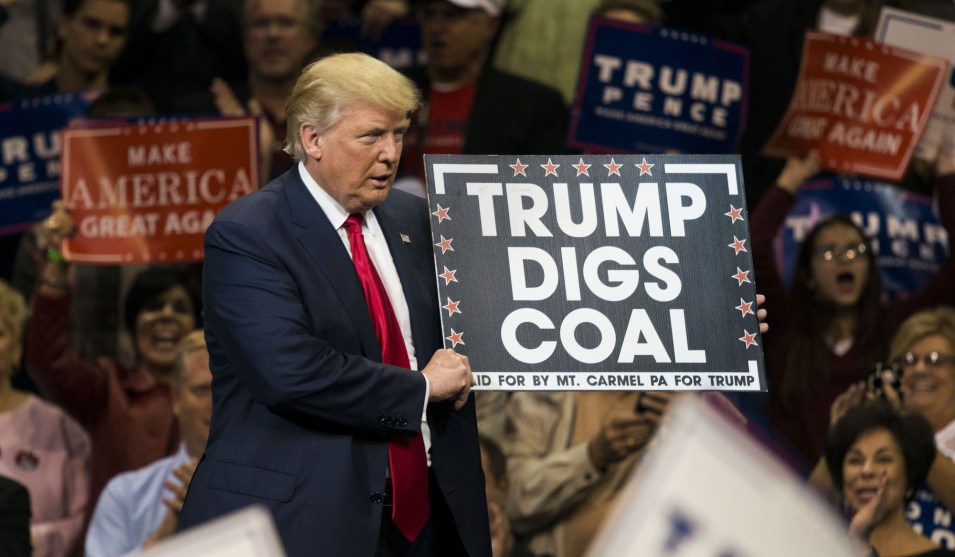

Bernard McNamee, President Trump's nomination to join an energy industry regulatory body, gives a talk in February at a Texas Public Policy Foundation event.Energy and Policy Institute/YouTube

Last February, Bernard McNamee stood behind the lectern in a crowded hotel ballroom in Austin, Texas, to deliver a speech on America’s energy future at a policy conference hosted by the Texas Public Policy Foundation. The right-wing nonprofit regularly convenes hundreds of state and federal lawmakers to craft conservative messaging on topics like climate change—an area of great interest to the group’s top donors, which include Exxon Mobil, the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation, and the Heartland Institute, a think tank best known for rejecting the scientific consensus of global warming.

McNamee was a natural choice to deliver this speech after his two-decade career representing oil and gas companies and advising climate change skeptic Rick Perry in the Department of Energy as deputy general counsel. Before returning this summer to DOE to lead its Office of Policy, McNamee ran TPPF’s energy policy division, where he supported litigation against the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan and worked alongside staffers like Kathleen Hartnett-White, who once crafted a guide for legislators that mocked the “unsubstantiated gloom-and-doom predictions propagated by global warming alarmists.” In front of the friendly room of industry representatives and TPPF members, McNamee argued for a “coordinated message” from politicians, corporate leaders, and pundits. “Fossil fuels make modern life possible,” reads the heading from one video McNamee aired for the crowd. The event culminated in a question-and-answer session during which McNamee admitted telling his son to “just deny” climate science. “I don’t care if you get an ‘F,’ ” he said. “I don’t care.”

The Senate confirmed McNamee Thursday to serve as a member of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the energy industry’s main regulatory body, on a narrow 50-49 vote. In this new role, McNamee’s opinions will not just be fodder for jokes at a conservative conference, but crucial guidance for the nation’s pipelines, power plants, and other components of the electrical grid. While formally housed within the Energy Department, FERC is an independent agency with five members appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Among its responsibilities are approving liquefied natural gas terminals and regulating the sale of electricity across state lines. Each commissioner serves staggered five-year terms and only up to three commissioners from the same political party are permitted to serve together at one time.

In this new position, McNamee’s oft-stated preference for fossil fuels could be a boon for the coal industry at a time when regional grid operators are increasingly turning to wind and other renewable sources of energy. “Fossil fuels are not something dirty, something we have to move and get away from,” he told conference attendees. “They are the key to not only our prosperity but to the quality of life.” And, he added, “also to a clean environment.”

Members of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission are supposed to be “neutral as to fuel source,” but McNamee’s speech clearly illustrates his preferences. He said renewable energy “screws up the whole physics of the grid”—a claim flatly refuted last year in an Energy Department report—and derided environmental advocacy groups for pushing “administrative tyranny” on state governments.

“How do you keep the lights on?” he asked. “With fossil fuels and nuclear.”

This idea is of particular importance to FERC, which unanimously rejected a proposal developed last year to boost struggling coal and nuclear plants. In a letter introducing this plan at the time, Energy Secretary Rick Perry said the security of the nation’s grid would be “threatened” by the closing of traditional power plants. “America’s greatness depends on a reliable, resilient electric grid powered by an ‘all of the above’ mix of generations resources,” he wrote, going on to say that only plants with “on-site fuel storage” could withstand the occurrence of man-made and natural disasters.

The administration’s preference for generators with fuel storage on site would disadvantage plants powered by natural gas or renewable energy on the dubious assumption that these sources of energy are less secure. Even industry-backed assessments, which acknowledge the importance of reliability across fuel sources, do not go nearly as far as Perry’s proposal. As DOE’s deputy general counsel for energy policy, McNamee spearheaded the administration’s plan, which was almost immediately greeted with skepticism from the commission and backlash from an unlikely coalition of oil, solar, and wind energy advocates.

The plan may have failed to garner a single vote from the FERC in January, but environmental groups are nervous that McNamee’s addition to the five-member body could foreshadow another attempt to boost the coal industry. The Republican commissioner he is replacing, Robert Powelson, was one of the few to strongly condemn this summer a leaked Trump administration proposal that would have forced operators to purchase electricity from coal and nuclear plants. The directive invoked the department’s emergency authority under a Cold War-era statute to halt the closure of more plants relying on coal and nuclear energy. McNamee was back at DOE leading the department’s Office of Policy when the proposal was developed.

“I don’t think it’s appropriate to put FERC in the arena of creating moral hazards in these markets,” Powelson told members of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. “These markets are working hyper-efficiently.”

Even the National Security Council weighed in and opposed the plan, which the White House reportedly shelved in October. But McNamee will have several other opportunities on the commission to further Trump’s agenda. As the third Republican on the commission, he could provide a decisive vote on a proposal FERC is considering from a gas-fueled plant in California that wants the state to reward plant operators “for their ability to supply electricity to the grid in a pinch”—another attempt to boost nonrenewables at the expense of other energy sources, the San Francisco Chronicle reported. “The results would be devastating for a state that has been a pioneer in sourcing its electricity from clean energy,” Kim Smaczniak, a staff attorney with Earthjustice, wrote in a blog post. “If McNamee were confirmed, it is far more likely that [the plant] will get [its] way.”

A vote in the plant’s favor could benefit a major Trump ally. Through a series of subsidiaries, the California plant is owned by Daniel Andrew Beal, who once donated nearly $500 million to Trump’s Atlantic City casinos and formerly advised his presidential campaign. The potential for McNamee to further support Trump’s activism around an issue that is cherished by his base has environmental advocates alarmed. “Bernard McNamee is clearly a political plant by the Trump administration who will rubber stamp dangerous fracked gas pipelines and push coal bailout schemes that will force taxpayers to pay tens of billions of dollars to prop up uneconomic coal plants,” said Mary Anne Hitt, senior director of Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, in a statement after his nomination. “This is indicative of a concerted effort to erode FERC’s longtime independence.”

In fact, it was not long ago when conservatives were railing against an attempt by the Obama administration to appoint a commissioner they believed to be biased against coal and other nonrenewable energy sources. Ron Binz, a former Colorado utility regulator Obama tapped in 2013 to chair FERC, drew scrutiny from Republicans due to his strong support for renewable energy and what some perceived as an anti-coal bias. Four months after his nomination—the most controversial in a generation—Binz withdrew his name from consideration, calling the process “a blood sport.”

McNamee’s two-month confirmation process has been far from smooth. On the floor of the Senate this week, Rhode Island Democrat Sheldon Whitehouse called him a “walking failure” and “conceivably the worst” energy nominee put forward thus far by the Trump administration. Even Joe Manchin, a Democrat from coal-loving West Virginia who is a member of the Energy and Natural Resources committee, rejected McNamee after his initially supporting his nomination. “Climate change is real, humans have made a significant impact, and we have the responsibility and capability to address it urgently,” Manchin said in a statement. “We can’t make progress if our public officials deny that a problem even exists.”

Nevertheless, McNamee managed to distance himself from the type of partisan work he would now have to pass judgment on as a commissioner. “Should I be confirmed to FERC, I will be not be biased for or against any resources or technologies; I will be an independent arbiter, making my decisions based on the law and facts,” he said in response to a Senate questionnaire after his hearing. Not all critics were satisfied. When asked if he would recuse himself should another Energy Department proposal to boost the coal industry come before the panel, McNamee said he would consult with an ethics counsel but remained noncommittal. The Harvard Electricity Law Initiative has already filed briefs with FERC that argue McNamee should be “disqualified” from ruling on two pending matters before the commission, each of which deals with fuel security. Senate Democrats made a similar request for recusal last month.

Critics have also taken issue with McNamee’s ethics pledge, which they say left out several potential conflicts of interest. Despite spending more than a decade in private practice, including several years representing energy industry clients, McNamee’s letter only mentioned his involvement with TPPF and a family trust.

“From my perspective, that seems to be inadequate to me,” Smaczniak, the Earthjustice attorney, told Mother Jones. “If anything, the standards should be stricter” for a FERC commissioner, who plays a judge-like role, she said.

FERC and the Energy Department did not respond to requests for comment.

As a commissioner, McNamee will complete the remainder of a term that ends on June 30, 2020. But before his time expires, he may have the opportunity to serve alongside another far-right Trump appointee if Kevin J. McIntyre, formerly the commission’s chair, ends up stepping down before his term ends in 2023. (After McIntyre was diagnosed with a brain tumor earlier this year, he relinquished his leadership role at FERC but said he plans to complete his term.)

The consequences of McNamee’s appointment could affect the energy industry for another generation. If nothing else, it will cement a transition in the agency’s history from being a largely independent body housed within the Energy Department to—like most everything else in the Trump era—an aggressively partisan body.

Three months before Trump nominated McNamee, FERC endured a brief, political firestorm when the commission’s chief of staff, Anthony Pugliese, criticized Democrats in an interview with Breitbart for “putting politics” above national security in their attempts to fight Trump’s efforts to expand energy infrastructure, like gas pipelines, through the northeastern part of the United States. Ex-FERC commissioner Jon Wellinghoff called the partisan nature of his comments “extremely unusual.”

“It’s never happened in the history of the commission, to my knowledge,” he told The Hill.

During the same February conference in which McNamee bashed renewable energy sources, he also was given a compliment that—more than anything else—might just indicate the type of commissioner he is bound to be once seated on the FERC later this month. Before his speech, McNamee was introduced by Kevin Roberts, TPPF’s executive director.

“The best thing I could say in our professional setting is that [McNamee] is a movement conservative,” Roberts said, “a true believer in every sense of that word.”