The ocelot is an endangered, wild cat native to North America.Leonardo Prest Mercon Ro/Getty

Forty-five years ago, on December 28th, 1973, President Richard Nixon, a Republican, signed a piece of monumental environmental legislation, the Endangered Species Act, into law. At the time, Nixon issued a statement in support of protecting wildlife that most sitting Republicans wouldn’t dare make today: “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” it said. “It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.”

The act now protects more than 1,500 species and remains one of the most powerful environmental laws on the books. Since its passage, several species, including the brown pelican, Louisiana black bear, and, of course, the bald eagle have recovered.

But somewhere along the way, what was hailed as a historic bipartisan achievement became deeply political. In the 45 years since its signing, conservatives have gone to extraordinary lengths to weaken the Endangered Species Act for the sake of economic growth—and the Trump administration has carried on the task of environmental deregulation with renewed vigor.

But before President Donald Trump was anywhere near the Oval, in the 1970s, the United States’ plants, animals, and the environment at large were in dire straits. Take, for example, the plight of the bald eagle, a bird native to North America that has long been considered a symbol of the United States’ strength, power, and freedom. By the early 1970s, an alarming number of bald eagles were dying, threatening the species’ existence. Between the pre-industrial era and the 1960s, the bald eagle’s population dropped from an estimated 100,000 to less than 1,000 due to habitat loss, illegal killing by ranchers, and exposure to DDT, the gnarly pesticide responsible for a slew of harmful environmental effects, including weakening birds’ eggshells. In short, America’s national symbol was on a fast-track to extinction.

At the same time, the country was in the midst of an environmental movement, a reaction to the horrific state of its natural spaces: In the late 1960s, Lake Erie became so polluted and consequently overrun by toxic green algae that it was declared “dead” by the media, a reference to the dead fish that had washed up on its shores. In 1969, the Cuyahoga River, saturated with oil pollution, caught fire. That same year, the nation witnessed the worst oil spill in its history (that is, until the Exxon-Valdez spill in 1989) in Santa Barbara, California. Add that to the looming threat of extinction for several iconic animal species—including the American alligator, Florida manatee, and grizzly bear—and the country’s wildlife was in serious jeopardy.

“We thought everything was good, but in point of fact, it wasn’t,” 92-year-old former House Representative John Dingell (D-Mich.), the longest-serving member of Congress in history and a sponsor of the Endangered Species Act, tells Mother Jones. “We were wiping out all kinds of species of fish and wildlife and didn’t seem to realize what we were doing to ourselves.” (A quick aside: Dingell runs an absolutely savage Twitter account, and he confirmed to Mother Jones that he does indeed write his own tweets.)

I should be more honest. https://t.co/bJDCW5pwjw

— John Dingell (@JohnDingell) May 23, 2017

In response to its moribund environment, the US government snapped into action. When Nixon took office in 1969, Congress had already passed the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, the first major law to protect species at risk of extinction, but the law fell short in a lot of ways—for example, it didn’t offer protection for plants or invertebrates—and it wasn’t doing enough to ensure recovery for some the country’s most loved creatures, like the bald eagle. So in the early 1970s, the Nixon administration began to push for a stronger law to protect endangered species, and the president recruited experts to help draft a new bill, which became the now-well-known Endangered Species Act of 1973. Remarkably, it sailed through Congress, passing 92-0 in the Senate and 390-12 in the House.

To Nixon’s credit, he realized the importance of endangered species to the American people, even if it wasn’t a personal priority. “He wasn’t an environmentalist. Far from it,” Lee Talbot, a member of Nixon’s Council on Environmental Quality and a co-author of the Endangered Species Act, tells Mother Jones. “But he was very concerned about his place in history and how he was perceived. He realized that endangered species was the subject of very wide interest. He didn’t see it as a political negative.”

Despite its popularity, the law created tension with farmers and developers who saw it as a barrier to economic growth. Over time, the way the act was regarded by politicians changed, especially as the species it protected vastly expanded to include those that may have been biologically important, but lacked charisma. In 1978, for example, the preservation of the Furbish lousewort, an endangered wildflower native to Maine, held up a $668 million hydroelectric project, TIME magazine reports. Many people thought the act went too far.

By the time Reagan moved into the Oval, there was a burgeoning sentiment that the country had grown tired of government regulation, intensified by Reagan’s brand of “government-is-the-problem” politics. In 1981, for example, President Reagan issued an executive order that required an economic review of all major government regulations, effectively freezing funding for the Endangered Species Act. But in 1982, Congress amended the Endangered Species Act to require species listing solely on the basis of scientific evidence—effectively excluding economic considerations.

The picture changed under Reagan,” Talbot says. “What had been a situation where the Democrats and the Republicans worked together—Reagan killed that. And I’ve never forgiven him for it.”

Legislative Attacks on the Endangered Species Act

1996-2018

Before the Trump administration, arguably the biggest threat to the ESA was a bill filed by Rep. Richard Pombo (R-Calif.) in 2005, ironically named the “Threatened and Endangered Species Recovery Act.” The bill would have eliminated key habitat protections and given more power to private landowners. Despite the support it received from the Bush administration, it failed in a Senate committee after a wave of protest from conservationists.

Now, as Republicans have had control of the White House and held majorities in Congress over the past two years, they’ve made it a priority to slowly chip away at the Endangered Species Act. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, there have been at least 419 “legislative attacks”—that is, actions intended to weaken federal protection of endangered species—against the Endangered Species Act since 1996, 116 of which occurred during the current 115th Congress.

Just this month, the administration released plans to roll back protections for the sage grouse, a controversial, ground-dwelling bird that happens to roost in prime oil and gas drilling territory in the West. And in November, the Trump administration approved seismic testing in the Atlantic, which could harm dolphins and endangered whales, biologists say. As I wrote earlier this year, Republicans have also sought to remove protections for vulnerable species including the gray wolf, grizzly bear, and the American burying beetle though amendments and stand-alone legislation. The administration has also been sued several times by environmental groups for failing to protect both domestic and foreign endangered animals like the North Atlantic right whale, the vaquita porpoise, and some humpback whale populations.

“Regrettably, this president is giving away public lands and weakening the laws we have finally got in place that protect fish and wildlife—that are meant to stop him from doing the things he’s trying to do,” Dingell, says. “Right now, the fight on those matters is very much under attack.”

Talbot agrees. “What [Trump] has done has been to provide an audience for people who don’t see the point of trying to save anything, who don’t want government mucking around with their lands and their resources,” he says. When I asked Talbot whether he’s confident the act will be around 45 years from now, he replied: “Given the present administration, I’m not confident in anything.”

So far, the Endangered Species Act has managed to keep its proverbial head above water, likely due to public support. A 2015 Tulchin Research poll found that 90 percent of voters still support the law, including 82 percent of conservatives. “The Endangered Species Act is actually a very popular law,” Rebecca Riley, legal director for the Nature program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, told me in July. “I think the American public has a general sense that letting a species go extinct is not in line with our values.”

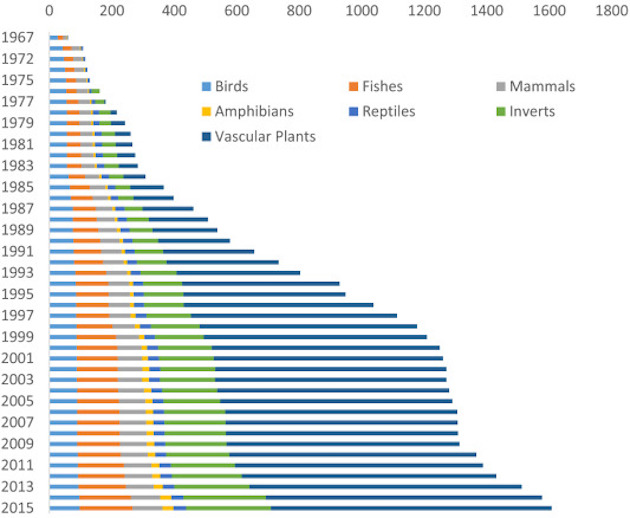

Number of U.S. listed endangered species over time & the changing distribution of listed species

That said, it’s not quite accurate to call the Endangered Species Act an unequivocal success. Before you jump out of your chair, let me explain. Proponents of the act say, “Yes, it has been successful because 99 percent of species listed haven’t gone extinct.” In saying so, they are correct. On the other side, opponents say, “No, it hasn’t been successful because very few species have been de-listed after recovering.” Technically, they’re also correct. The problem is, there is no control group to test what would happen if the species weren’t listed—we have no way of knowing what would have happened if, say, the bald eagles had never been federally protected.

“Because there’s no credible scientific evidence about the ESA’s effectiveness, you have both sides just choosing anecdotes or data patterns that support their perspective,” says Paul Ferraro, a professor of business and engineering at Johns Hopkins University. “Could you imagine if we approached medicine and public health in the same way? If we were doing something for 40 years and still debating its effectiveness?”

In 2007, Ferraro conducted a study in which he compared the recovery rates of species listed on the Endangered Species Act with similar species not listed under the act. He found that listing a species is on average, “detrimental to species recovery” if the listing is not also supported with “substantial government funds.” The moral of Ferraro’s work is that listing a species, in general, does nothing—and may actually have a negative effect—if no is money involved. (The US government typically hands out grant money to states and territories to protect species on a case-by-case basis.) Even so, one study doesn’t prove much. “This is not the final word on ESA effectiveness,” Ferraro says. “And I would never call for repealing it on the basis of that study—or any other studies.”

Still, on an unscientific scale from zero to 10 (with 0 being useless and 10 being perfect), Ferraro says he’d rate the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act at a 4. “Having it is better than not having it,” he says.

I posed the same question to Riley, a lawyer with the NRDC, who gave the act an 8. And Talbot, who wrote the act, when asked the same question said, “Do you know any legislation that would get a 10?” implying that he would give it a very high score. But if he could do it all over again, Talbot says he would have included more incentives for private landowners to be “effective conservationists.” After all, about half of threatened and endangered species have habitats that fall on private land, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service.

It’s also a matter of expectations. Environmentalists argue that a species’ recovery from near extinction take decades. “When you wait to put protections in place until a species has declined to the point where it’s facing extinction, often times, its a result of 100 years of action,” Sarah Greenberger, senior vice president of conservation policy for the National Audubon Society, tells Mother Jones. “It’s not easy to reverse.” Even in the case of the bald eagle—which would have presumably been a national embarrassment had the government failed to save it—the bird wasn’t down-listed from “endangered” to “threatened” until 1995. In 2007, it officially graduated from the list of endangered and threatened species, nearly 34 years after the passing of the Endangered Species Act.

Looking forward, the next 45 years for the Endangered Species Act are only going to get more tumultuous. Assuming it survives the Trump administration, a growing global population and climate change are going to make species and habitat conservation that much more difficult—and vital.

“When you ask most people, they value the fact that our rivers don’t catch on fire, that we have wildlife, that we have these iconic landscapes that define us… but that doesn’t come without thinking about it—and choosing to value it,” Greenberger says. “On this anniversary, “we have to decide what kind of legacy we want to continue into the next 45 years.”