Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke speaks to President Donald Trump during the National Christmas Tree Lighting ceremony in Washington, DC on Nov. 30, 2017. Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images

This story was originally published by Reveal. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Park officials scrubbed all mentions of climate change from a key planning document for a New England national park after they were warned to avoid “sensitive language that may raise eyebrows” with the Trump administration.

The superintendent of the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park in Massachusetts had signed off a year ago on a 50-page document that outlines the park’s importance to American history and its future challenges. But then the National Park Service’s regional office sent an email in January suggesting edits: References to climate change and its increasing role in threats to the famous whaling port, such as flooding, were noted in the draft, then omitted from the final report, signed in June.

The draft and the emails were obtained by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting in response to a Freedom of Information Act request.

The documents provide a rare peek behind the usually closed curtains of the Trump administration. They illustrate how President Donald Trump’s approach to climate change impacts the way that park managers research and plan for future threats to the nation’s historic and natural treasures.

The editing of the report reflects a pattern of the Trump administration sidelining research and censoring Interior Department documents that contain references to climate science.

Earlier this year, Reveal exposed an effort by park service managers to remove references to human-induced climate change in a scientific report about sea level rise and storm surge at 118 national parks. The Guardian recently reported on the Trump administration’s efforts to stall funding for climate change research in the Interior Department by subjecting research projects to unprecedented political review by an appointee who has no scientific qualifications.

In a survey by the Union of Concerned Scientists, government scientists reported being asked to stop working on climate change and connecting their science to industry actions. These are just a few of the examples of science under siege compiled by Columbia University in its “silencing science” tracker.

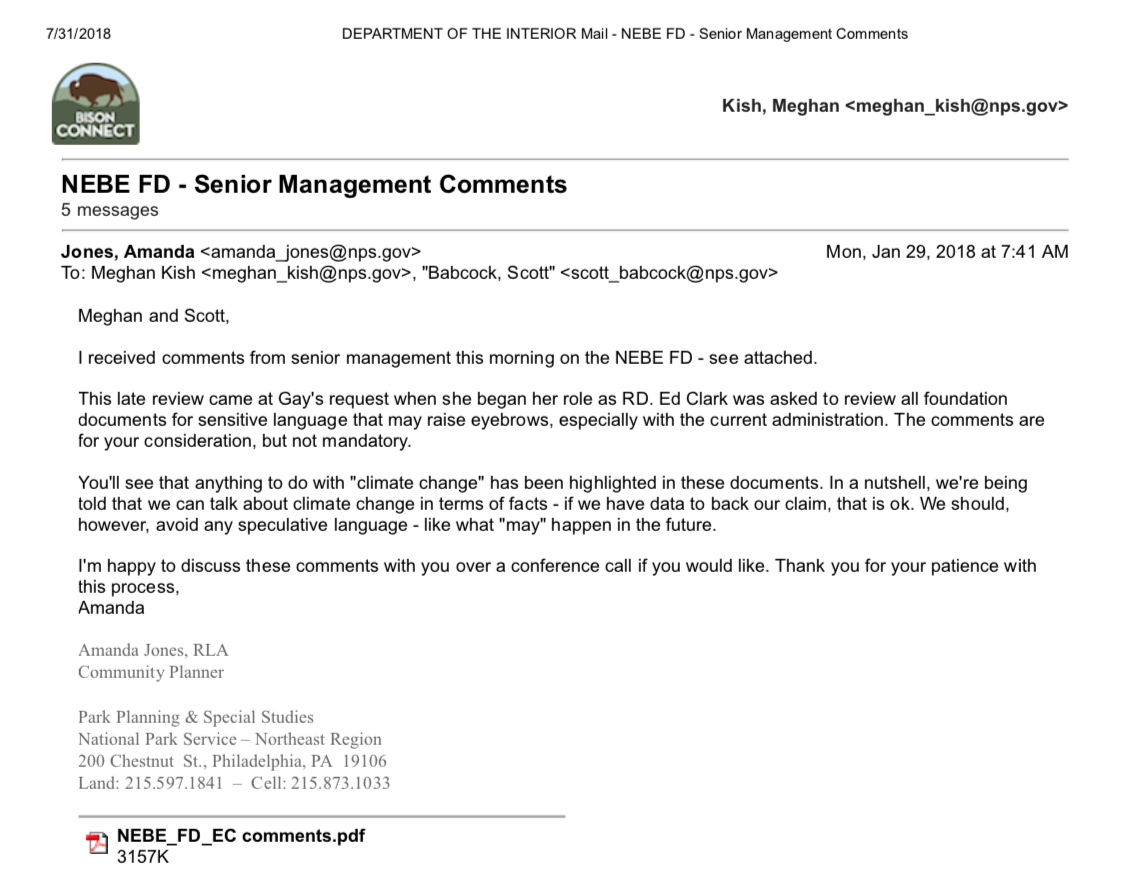

The email suggesting changes in the New Bedford park report was sent in January by Amanda Jones, a community planner with the park service’s northeast region.

“You’ll see that anything to do with ‘climate change’ has been highlighted in these documents. In a nutshell, we’re being told that we can talk about climate change in terms of facts—if we have data to back our claim, that is ok. We should, however, avoid any speculative language—like what ‘may’ happen in the future,” she wrote to Meghan Kish, the New Bedford park’s superintendent.

Scientists say telling park managers to avoid references to “what may happen in the future” is worrisome.

Steven Beissinger, a professor of conservation biology at University of California, Berkeley who reviewed the emails and edits in the New Bedford report, called it “irresponsible to future generations of Americans” for the park service to direct managers to ignore research on the future risks of rising sea levels, risks to endangered species, worsening wildfires and other effects.

“We should have confidence in scientists’ projections and prepare for those kinds of scenarios,” Beissinger said. “We can hope they won’t happen, but we surely want to be prepared for them. We have to be looking at the future because places are going to be changing.”

A comparison of the draft and final documents shows all 16 references to “climate change” were removed.

Park service officials involved in editing the New Bedford report did not respond to repeated requests for interviews. But a park service spokesman said parks are told to “address issues like climate change … using the best available scientific information.”

“Sound management requires that we rely on specific, measurable data when making management and planning decisions,” Jeremy Barnum, chief park service spokesman, said in an email response to Reveal. “Climate change is one factor that affects park ecosystems, resources, and infrastructure.”

Barnum did not answer questions about the deletions from the New Bedford park report, which is known as a “foundation document.” But he said such documents are reviewed “to ensure that they are consistent with current policy and directives.”

The New Bedford park was created by Congress in 1996 to preserve 13 city blocks of a Massachusetts seaport that was home to the world’s largest whaling fleet in the 19th century. The park tells the broader history of American whaling.

Flooding from rising seas, increased snow melt and stormwater, larger storm surges and extreme heatwaves are among the threats from human-caused climate change to the park’s historic structures. A 1960s hurricane barrier that protects New Bedford is vulnerable to widespread failure in a 100-year storm if sea levels rise by 4 feet. A Category 3 hurricane could breach the barrier at current sea levels.

The original draft obtained by Reveal was dated Sept. 29, 2017, and signed by Kish. The final version, signed by Kish and Gay Vietzke, regional director of the park service’s northeast region, is dated June 2018. It is not yet available online, but the park sent Reveal a printed version of the 50-page booklet.

Among the sections highlighted for review and then deleted were references to climate change in charts outlining threats to New Bedford’s historic structures, port and natural resources.

This sentence was removed: “Climate change and sea level rise may increase the frequency of large storms and storm surge, rising groundwater tables, flooding, and extreme heat events, all of which have potential to threaten structures.” In its place, the final document says: “Large storms and storm surge, rising groundwater tables, flooding, and extreme heat events all of have the potential to threaten structures.”

Also, in a section about research needs, the original draft called for a “climate change vulnerability assessment.” That’s missing from the final version, which instead calls for an “assessment of park resilience to weather extremes.”

In several places, the phrase “changing environmental conditions” is substituted for the deleted term “climate change.”

Also deleted is a mention of how development near the park “could impact character and ambiance of historic district.” Elsewhere, a reference to “gentrification” is replaced with “urban renewal.” Mentions of declining park service funding and the limited control that managers have over privately owned buildings in the park are also removed. The museum in the park, which contains ships, skeletons and whaling artifacts, is privately owned.

The January email suggests that the edits are part of a broader review of foundation documents that Vietzke assigned a park service official named Ed Clark to conduct for the northeast region, which includes 83 national parks in 13 states.

“This late review came at Gay’s (Vietzke) request when she began her role as (regional director). Ed Clark was asked to review all foundation documents for sensitive language that may raise eyebrows especially with the current administration,” the email from Jones says. She wrote that the edits are “for your consideration, but not mandatory.”

Jonathan Jarvis, who headed the National Park Service under President Barack Obama, said that the direction to scrub the foundation documents must have originated from Trump administration officials, because he knows regional director Vietzke well.

“She would not be doing this of her own accord. This would have come down from on high, verbally,” he said.

Jarvis said career park service officials told him that their supervisors verbally directed them to make changes in a sea level rise report so that they did not leave anything in writing.

Scientists say climate change already is affecting parks and that the threats will increase if people continue to release greenhouse gases, which come largely from burning fossil fuels.

Jarvis was director of the agency in 2012 when Hurricane Sandy brought devastation to the northeastern coast, including several national parks. The parks incorporated climate change projections into rebuilding efforts, including moving utilities out of the basements in the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, both of which were flooded by the storm.

“Without considering climate change, we would have put them back in the basement. That’s why it has to be in a planning document,” Jarvis said.

In many national parks, flowers are blooming sooner and birds are nesting earlier, temperatures and seas are rising, and glaciers are disappearing.

Mary Foley retired in 2015 after 24 years as the chief scientist for the park service’s northeast region. She said she was frustrated during the Bush administration because the park service lacked permission and funding to solicit key research about climate change. But she said the Trump administration’s policy of sidelining climate science is much more concerning. Now much of the science has been done, but the unwritten policy seems to be to order park managers to ignore it, she said.

“Managing a park is a difficult and expensive task,” Foley said. “It’s pretty shortsighted to ignore future climate change. If you are going to plan for construction of a visitor center you wouldn’t want to put it where sea level rise is going to challenge that structure.”

But Foley and other former park service leaders said they hope that park managers will incorporate science into the planning for parks even if they scrub documents to please Trump’s team.

“Current managers are pretty knowledgeable of the implications of climate change. Whether or not that is written into formal documents, I don’t think that they will ignore it,” Foley said.

“The bottom line is, this is just paper,” Jarvis added. “You can’t erase in the superintendents’ minds the role of climate change. They’re going to do the right thing even if it’s not in the policy document.”

This story was edited by Marla Cone and copy edited by Stephanie Rice.