lolostock/Getty

For a lot of people, contact lenses are a daily necessity. Market research shows 45 million Americans, about one in eight, wear contacts, meaning the United States alone consumes somewhere between five and 14 billion lenses annually. And now, new research shows all those contact lenses may end up as micro-plastic pollution in our soil, rivers, and oceans.

An estimated 20 percent of contact-lens wearers, studied as part of a 400-person online survey, flush their lenses down the sink or toilet, as opposed to placing them in the trash as industry experts recommend. That amounts to 20 metric tons of plastic, or 20,000 kilograms (about 44,000 pounds), flushed per year—about the weight of a small airplane. The biggest culprit? Daily-use lenses, which occupy about 40 percent of the market.

The new research, which was presented Sunday at the 256th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society, adds to growing concern about all kinds of plastics and micro-plastics—those less than five millimeters in diameter—that have plagued our land and waterways for decades. Every year, an estimated 19 billion pounds of plastic ends up in the ocean, and that amount is expected to double by 2025. These plastics litter coral reefs, are ingested by sea creatures and birds, and can even make their way into the fish we eat.

“We wondered: How many lenses are there in the US?,” Rolf Halden, a professor in the Ira A. Fulton School for Sustainable Engineering at Arizona State University and a lead researcher on the analysis, tells Mother Jones. “And then, what happens to them if a fraction of them find their way into wastewater treatment plants?”

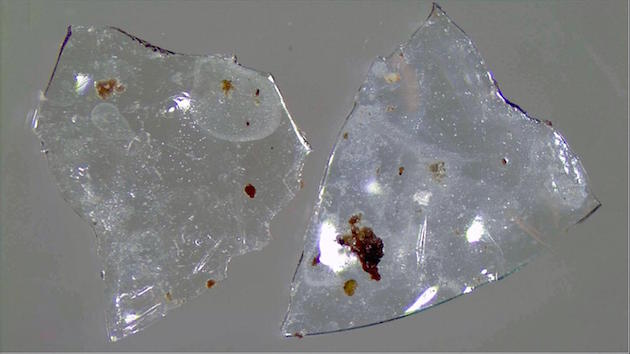

To find out, Halden’s team conducted an online survey to assess contact-user behavior, including how many people normally flush their lenses, and also visited a wastewater treatment plant in the United States as a model of what to expect across the country. They discovered the majority of lens plastic treated at wastewater plants doesn’t degrade and is likely becoming part of “municipal sewage sludge.” Nation-wide, about half of that sludge is sent to landfills, according to Halden. But the other half, he says, is applied as fertilizer to land. “This amounts to at least 11 thousand kilograms per year of contact lens material applied on American soils,” he says.

Contact lenses recovered from treated sewage sludge

Charles Rolsky

From land, the contact lenses can be ingested by insects and birds or enter waterways as rainwater runoff. “It’s safe to say that some lenses might make it into the surface water,” that is, water that will run into the ocean, says Halden. “We just believe that fraction, under normal conditions is very small, probably less than 1 percent.”

So, by mass, contact lenses are “not a big player” in ocean pollution when compared to other forms of plastic, like plastic bags and packaging, he says. For example, contact lens packaging alone requires somewhere between seven and 15 million kilograms of plastic annually, most of which isn’t recyclable. “That’s equivalent to the amount of polypropylene it would take to make 400 million toothbrushes,” he says.

But, even a small amount can have an impact and what’s crucial about recognizing this kind of pollution is that, according to Halden, there’s an easy fix: Simply stop flushing those contacts.

“Here’s the bottom line: Put those lenses, if you use them, into the solid waste stream, meaning in your garbage can, and encourage the manufacturers of contact lenses to provide recycling opportunities.”

Halden and his team expect their research to be published in an academic journal in the coming months.