National Weather Service

The past seven days have set global heat milestones and sparked safety concerns from Quebec, where at least 34 people have died in the province from the heat and humidity, to northern Siberia, home to the coldest town on Earth, which recorded temperatures “40 degrees above normal” on Thursday.

In Denver, the temperature reached an all-time high of 105 degrees. Just shy of 98 degrees, Montreal broke a 147-year-old record with its hottest measurement ever. In Bergen County, New Jersey, 81-year-old Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-N.J) passed out from the 90-degree-heat at a local fire department event.

Last week’s weather is yet another example of how climate change has created more frequent, extreme weather events. Nick Humphrey is a meteorologist and geoscientist in Lincoln, Nebraska, who runs the “Ocean’s Wrath” blog and studies the nature of these events in relation to ocean storms and climate. He was one of the first researchers to note the historic heat event this week in northern Siberia. In a blog post, Humphrey wrote, “2018 has unfortunately been a prime example of global warming’s effect on the jet stream. And northern Siberia has been getting blowtorched by heat that refuses to quit because of an ongoing blocked pattern favorable for intense heat.”

We asked Humphrey to put the historically high temperatures in context of other heat waves and explain the ways in which climate change is responsible for an increasing number of extreme weather events. During our conversation, he described how heat index figures, which encompass heat and humidity, may still undersell the brutal heat. “Those values are assuming you’re in the shade,” he said. “If you go out in the sun, it can feel 10 to 15 degrees warmer.” Mother Jones spoke to Humphrey by phone on an 84-degree day in Lincoln.

Mother Jones: In what ways is climate change responsible for the extreme weather we have seen recently?

Nick Humphrey: If you think of climate change as a kind of disorder the planet has, one of the greatest symptoms is increasing extreme weather events. Prior to human-induced global warming, climate changes were relatively slow over the course of hundreds to thousands of years.

Here on the [Great] Plains, it went from one of the coldest Aprils on record to one of the hottest Mays on record—and our records go back to 1887! In Eugene, Oregon, they had their coldest temperature ever in July. They had a low of 38 degrees, and their average lows are usually in the 50s. Even in a global warming pattern, somebody gets cold.

The city of Eugene, in #Oregon's Willamette Valley, experienced their coldest July temperature on record this morning! #ORwx Details: https://t.co/JPvBiMjWyZ pic.twitter.com/zOygkekdj0

— WeatherNation (@WeatherNation) July 3, 2018

MJ: Are the heat events of the last few weeks as historically significant as some news outlets are claiming?

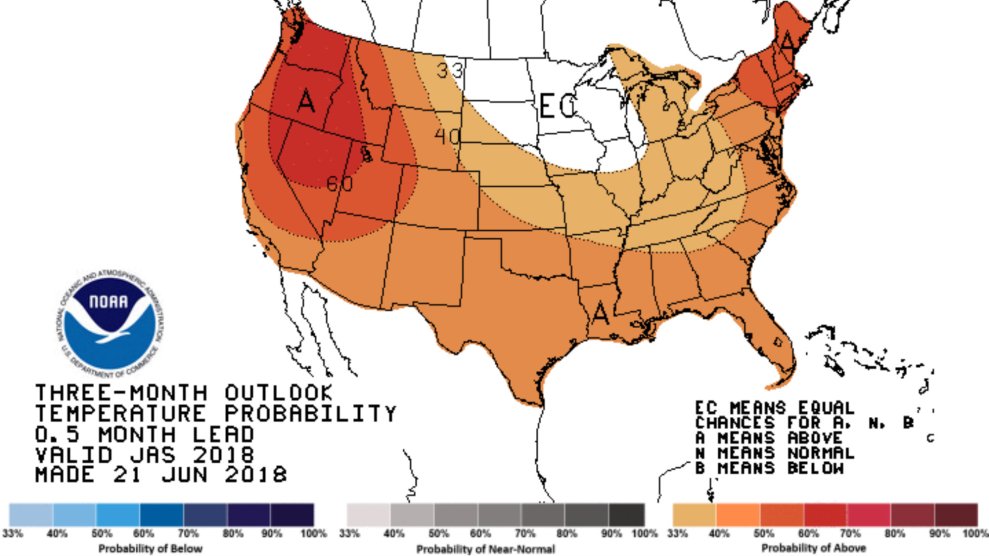

NH: In the United States, these events are more significant because of what I see beyond the United States. Climate change is a problem of a global system, and the whole system matters. Much of the Northern Hemisphere is reporting significant heat throughout, so you’re seeing it on the Great Plains, the east coast of the United States, eastern Canada, Ireland, Britain, France, Belgium, Germany. Russia has been particularly concerning to me, where they are getting 90-plus-degree temperatures up near the shores of the Arctic Ocean. These are regions that get abnormally cold, and in the clashing of that very cold and very warm, it often leads to very intense storms, [like the] five or six nor’easters that impacted the eastern seaboard.

Global warming creates these extreme heat events, it creates a few of these extreme cool events, and it creates a lot of disruption when these systems sit in place for long periods of time and cause the same extreme conditions over weeks of time.

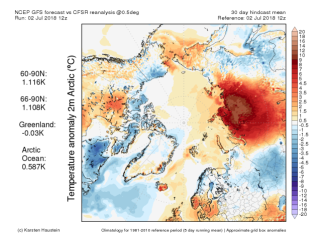

MJ: You wrote about northern Siberia experiencing record-high temperatures. Most people tend to associate Siberia with the coldest place on Earth. What led you to focus on the surprising heat event there?

NH: I’ve never seen something like this on this kind of scale. You now have hot weather—like 80- and 90-degree weather—marching on the door of the Arctic. That kind of heat, if it starts to become a more persistent thing, means the planet has gained the ability to produce heat that can more rapidly melt permafrost.

MJ: What are other ways these heat events affect the environment?

NH: Two of the concerns I have are heat stress on humans and animals, but also on crops. When you start getting temperatures above 86 degrees, it starts to cause heat stress on certain crops—corn, soybeans, wheat. They don’t grow as well. If the crops end up failing, people can’t afford their food.

MJ: How is climate change affecting this process in ways we are not recognizing?

NH: Once you put something in the atmosphere like these greenhouse gases, we lock in our contribution to what the planet is going to be in the future. But it’s not just our contribution. In the news, it is always talked about as “human emissions,” but it’s also the feedback of what the Earth does in response to what humans do to amplify what humans have done. Once you reach certain tipping points, the Earth takes over and amplifies what we’ve done to make things go faster.

These increasing heat events, these extreme weather events—that’s all a process of the Earth trying to speed itself up to get to a new stable state. Is that stable state going to be one that’s suitable for humanity?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.