Grist / Justine Calma

This story was originally published by Grist and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On a hot summer day in New York City last July, Ajohntae Dixon was studying at home when he began struggling to breathe. With no air conditioning in his apartment, the temperature inside surged, and the 15-year-old’s gasping quickly progressed into a full-blown asthma attack under the oppressive heat. He took his inhaler and then tried his nebulizer, but he was still fighting for air.

By 8 p.m., Dixon was in the emergency room. And after that overnight hospital stay, he and his mom installed air conditioners in each of their rooms to cut the chances he would have to go back.

“I’m not a huge fan of hospitals,” says Dixon, who lives in the Bronx neighborhood of Hunts Point.

Dixon is homeschooled, but he’s an active teenager and a budding leader in his community. He participates in a “social circus” supported by Cirque du Soleil, where he has learned to juggle and ride a unicycle. He also recently joined a youth program at the nonprofit organization, The Point Community Development Corporation (more commonly known as The Point CDC), which raises awareness of problems in Hunts Point, from pollution to lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables.

Another of those challenges is exposure to ambient heat levels that are generally higher than the rest of New York City. While Dixon was able to make it to a hospital during his asthma attack last summer, many others who suffer from chronic health conditions aren’t so lucky when the temperature spikes.

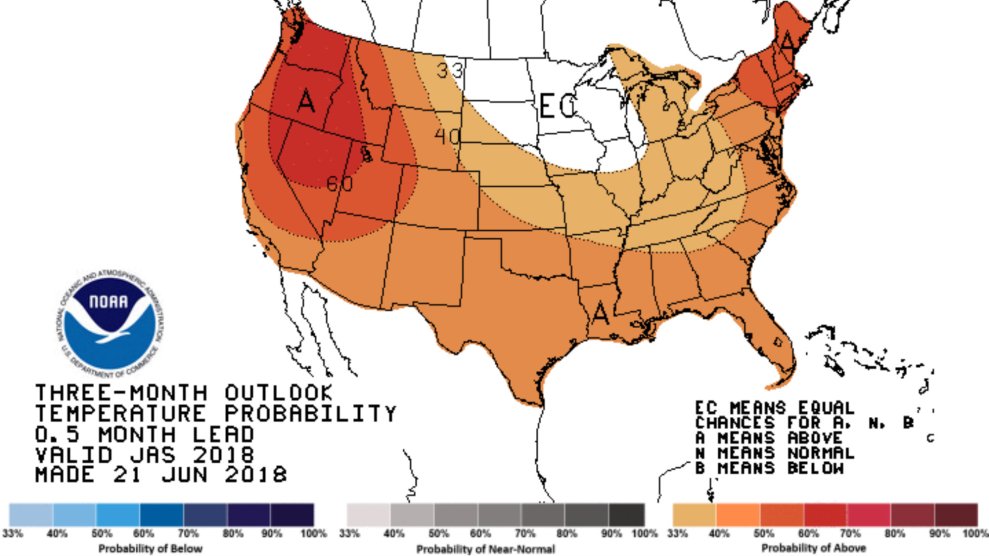

New York City isn’t the only place that’s increasingly vulnerable as temperatures rise. Extreme heat kills more Americans each year than any other weather-related event. In California this past week, triple-digit temperatures shattered records and caused tens of thousands of Los Angeles residents to lose power for days. And more than 50 deaths have been linked to a heat wave that hit Quebec earlier this month.

Thanks to the “urban heat island effect,” cities are significantly warmer than their surrounding suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas. And within a city like New York, a long history of disinvestment in black and brown neighborhoods means these communities are heating up the most. Hunts Point is one of the New York City neighborhoods with the highest risk of heat-related deaths. It’s also a place where 98 percent of residents are people of color.

“Extreme heat is really becoming one of the most dangerous climate impacts,” says Annel Hernandez with the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, which has made tackling the urban heat island effect the top priority in its climate justice agenda for this year. “While hurricanes and storm surge happen every five years or even longer, extreme heat is something that’s happening every single year.”

Heat-induced fatalities are entirely preventable. And with climate change threatening to increase the death toll, grassroots community leaders and city officials in New York are taking action. One solution is to beef up the city’s response to extreme weather events by providing ways for residents to keep cool and ensuring people know how to access them. But to save more lives as climate change makes the problem much worse, the city will have to undo decades of urban development that has put many communities of color at risk when the temperature spikes.

Summer heat waves pose a serious public health threat. As people lose water and salt from sweating due to prolonged exposure to high temperatures, they can experience symptoms of heat exhaustion—muscle cramps, weakness, dizziness, headache, nausea, and fainting. If left unchecked, heat exhaustion can progress to heat stroke—which happens when the body can no longer regulate its core temperature. People get confused, lose consciousness, and can also suffer seizures.

Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that upward of 600 people die from extreme heat every year. The deadly threat from heat waves caught the country’s attention in 1995, when one killed 739 people in Chicago. Every year, New York City sees an average of 450 heat-related visits to the emergency room and more than 100 deaths attributed to sweltering conditions. African Americans make up less than 25 percent of the city’s population. But between 2000 and 2012, they accounted for nearly half of the city’s fatalities.

The NYC Environmental Justice Alliance worries that the actual death toll might be even higher. That’s because the city’s definition of a “hot” day and its criteria for determining how to attribute deaths to a heat wave can differ from other researchers’ standards. Various independent studies have estimated the number of yearly heat-related deaths in New York City could range between 200 to more than 600.

Like climate change, the urban heat island effect is man-made. Cities are often 2 to 8 degrees warmer than their surrounding areas thanks to traditional urban design choices—tall buildings, dark roofs, and black pavement all attract and absorb the sun’s rays. At night, when our bodies need to cool down to recuperate from a hot day, the difference can be even starker: Urban centers can range as much as 22 degrees warmer than rural areas nearby. A 2013 study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, showed that, according to 2000 Census data, people of color are up to 52 percent more likely to live in urban heat islands than white people. As a result, they face more health risks during a heat wave. (Grist board member Rachel Morello-Frosch was a coauthor of the study.)

Within a “heat island” there can be hotspots, neighborhoods that heat up even more than the overall city. “Fenceline communities,” where residents live alongside heavy industry, have more surfaces that trap heat and fewer trees and green spaces that help cool an area down. Hernandez from the Environmental Justice Alliance says that the New Yorkers who face the brunt of more frequent extreme heat events “live in communities that have already been burdened by polluting infrastructure for a long time.” In other words, heat is an added environmental burden to the same low-income residents and people of color who are already living in contaminated communities.

Hunts Point’s primarily black and brown residents live near heavy industry that fulfills two city-wide necessities: bringing food in and getting waste out. It is home to the largest wholesale produce market in the world and hosts more than a dozen waste-transfer stations. (The South Bronx handles almost a third of New York City’s waste.) As a result, a neighborhood with 13,000 people has one of the highest concentrations of truck traffic in the Big Apple. And those vehicles pipe in hot exhaust to the already sweltering community—contributing to higher rates of asthma linked to pollution.

Hunts Point has long been a part of the city with one of the lowest parks-to-people ratios. But over the past decade, locals have pushed to develop more green space along its riverfront. “Traditionally, this community has been understood by the City of New York as an industrial area in nature,” says Angela Tovar, director of community development at The Point CDC. “So there was no prioritization of street trees, of any sort of mitigation to be able to bring down the temperatures in the community.”

Indoor temperatures in large city buildings are often even hotter than outdoor ones, especially at night. So people without air conditioning, senior citizens, and anyone who has difficulty getting out and about to find a place to cool down are especially vulnerable during a heat wave. People with chronic medical, mental health, or developmental conditions are also at greater risk.

According to the city’s Office of Emergency Management, a majority of heat-related deaths occur in homes without AC. In all twelve New York neighborhoods with the highest heat vulnerability, between 21 to 34 percent of residents are living below the city’s poverty threshold. In Hunts Point, the average median household income is slightly more than $22,000; after paying for rent and food, many residents don’t have enough left over to buy an air conditioner or pay for the extra electricity needed to power it.

According to an NYC Environmental Justice Coalition analysis, more than half of the city’s public housing residents live in its most heat-vulnerable neighborhoods. And there are additional barriers for people who want to install air conditioners in public housing: Residents must apply for approval and pay an annual fee for each air conditioner they put in their homes.

A 2016 Columbia University study projected that by 2080, up to 3,300 New Yorkers could die each year from intense heat made worse by climate change. So the city is in a race against time to stem the trend of steadily rising temperatures and save residents’ lives.

New York City is one of the cities in the developed world that is most vulnerable to the dangers of urban heat, says Kurt Shickman, executive director at Global Cool Cities. Part of the reason is its large immigrant community. Recent transplants coming from hot, rural regions may not be prepared for what they’ll face in a crowded city.

“Those can be some of the most vulnerable populations,” Shickman explains. “In many cases, they’re sort of thinking about heat in the context of where they came from rather than how it affects New York.”

During a heat wave earlier this month, with temperatures reaching 96 degrees Fahrenheit, local nonprofits voiced concerns about how effective the city government was in making “cooling centers” available to the public. These are often neighborhood libraries, recreation centers, and senior centers that are repurposed during heat waves to offer the public access to air conditioning.

During this most recent heat advisory, the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance called around 50 different cooling centers in the city to survey how they were operating. They found that 35 sites were functioning as intended, but more than a dozen were not properly identified as places where overheated residents could seek refuge. Another dozen sites were not open for a variety of reasons, including construction and broken ACs. Some operators were unaware that they were city-designated cooling centers.

The city’s Office of Emergency Management claims it provided all its partners with signage prior to the start of summer. If an AC breaks down or a cooling center can’t perform its duties for any reason, the office says that it immediately updates its online finder tool to remove that location from its list of facilities.

“We are in constant communication with our partners who provide real-time updates on cooling centers,” explains Omar Bourne, deputy press secretary for the department. “Any cooling center experiencing issues is immediately taken out of service.”

The city releases its list of cooling centers during the first day of a heat wave. Environmental justice advocates contend that more needs to be done. People who have the hardest time escaping a dangerously hot apartment—like seniors and people with disabilities—might miss announcements made online or on social media and need more of a heads up to figure out how to get to a cooling center, critics say.

“They’re sort of announced in an ad hoc fashion, kind of like they’re calling out a flash mob,” says Stephen Roundtree, environmental policy and advocacy coordinator at WE ACT for Environmental Justice, an organization based in West Harlem. “It’s cool if you’re in the loop with it, but it’s not a predictable or a super dignified way of telling people where they can go to get resources.”

In 2016, Roundtree’s organization surveyed more than 500 residents in northern Manhattan— including neighborhoods like Harlem and Washington Heights, which are also largely communities of color—and found that although 50 percent of respondents reported having experienced symptoms related to heat sickness, fewer than 20 percent had ever been to a cooling center. That’s in part because many people don’t know where to go or aren’t aware that cooling centers even exist. WE ACT recently held a design contest to come up with a creative logo for signs that will help lead people to their closest cooling center.

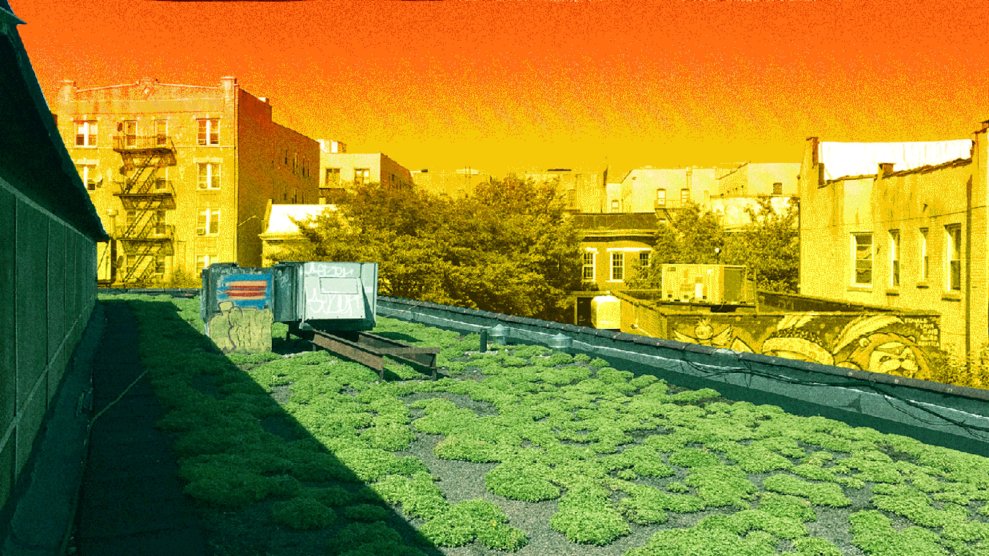

Improving cooling center signage and generally making the facilities more inviting is part of New York City’s $106-million “Cool Neighborhoods” plan, launched last year to mitigate the health risks of extreme heat. It includes painting surfaces white, planting more trees, creating green roofs, and building other green infrastructure to cool down several neighborhoods. The principles behind the plan are simple: Evaporation from plants has a cooling effect. And painting roofs white will help to reflect solar radiation rather than allowing the building to absorb it.

“Extreme heat is one of the many impacts of our changing climate,” says Jainey Bavishi, director of the city’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency. “We know that these impacts will only intensify, so the city is actively pursuing strategies to both change our physical environment to reduce the drivers of extreme heat while protecting the most vulnerable New Yorkers inside their homes.”

Part of the plan involves the NYC’s health department partnering with organizations like The Point CDC to tailor strategies to specific communities, beginning with sending out volunteers and health professionals to check on older folks and others who might otherwise be trapped in a sweltering apartment during a heat emergency. Hunts Point is one of three neighborhoods where officials are piloting the initiative this summer. If all goes well, they’ll expand the project across the city.

Kurt Shickman, who consulted on the Cool Neighborhoods plan, applauds the city government for recognizing the unique characteristics of its most heat-vulnerable communities—and then focusing its policy interventions on helping them. “In a neighborhood like the South Bronx, there’s clearly room for more vegetation,” he says. “So how do you plant more trees and how do you maintain those trees such that they grow to a shade height?”

Ajohntae Dixon carries box fans as he prepares for another New York heat wave.

A key to Cool Neighborhoods’ success will be the city’s ability to rally the efforts of many different actors—including multiple city agencies, outside researchers, and grassroots groups like The Point. Shickman calls New York City “one of the best in the world right now” when it comes to tackling the urban heat problem. That’s in large part because of the relationships it’s fostering between diverse stakeholders so that they can take on the issue together.

There’s an added benefit of the coordinated effort: Making strides to cool down New York City’s hottest neighborhoods will also help it address climate change (and vice versa). Beyond repainting surfaces and adding more vegetation, moving toward cleaner energy sources could keep summers in the city from getting considerably hotter, saving lives now and in the long term, according to NRDC senior scientist Kim Knowlton.

“It could mean, by the 2080s, the difference between a 15-degree hotter summer day and just a 3- or 4-degree hotter day—something we can cope with as a society versus something that we will be very challenged to cope with,” Knowlton explains. “It’s a great opportunity to do the right thing.”

Before this summer’s first heat wave enveloped New York, Ajohntae Dixon had made sure he was prepared, buying two 1.5-foot box fans to supplement the ACs he and his mom had installed last year. And he chose to sequester himself indoors as temperatures rose above 90 degrees for five days straight just before Independence Day.

“It’s a little disheartening,” Dixon says. “There are often times I want to do things, and it’s a lot harder when it’s so hot outside.”

But he knows he’s simply taking care of himself—and preventing another unwanted trip to the hospital.