Bella Romero Academy’s playground, with Extraction Oil and Gas' proposed site just beyond the fence.FracTracker

In one of the most fracked counties in the country, a fight is underway between environmental justice advocates and the Colorado commission that oversees oil and gas development. Four environmental and civil rights groups are suing the commission for allowing a company to build 24 oil and gas wells by a public school in a low-income area—after the same company tossed its original plans to build near a charter school serving mostly white, middle-class families.

Back in 2013, the company Mineral Resources was granted a permit to drill a few hundred feet from Frontier Academy, a majority white charter school in Greeley, Colorado. But after parents and neighborhood residents strongly resisted, the project was delayed. The following year, the Denver-based energy company Extraction Oil and Gas acquired Mineral Resources and abandoned the plans to frack near Frontier Academy. The site, Extraction explained in an internal analysis, was “not preferable” for oil and gas development because of its proximity to the school and its playground.

Instead, Extraction began scouting other locations in Greeley, a small city about 50 miles northeast of Denver. In May 2016, Extraction Oil and Gas filed a new application. This time, Extraction selected a site even closer to another school: Bella Romero Academy. The student population at Bella Romero is more than 87 percent Latino or Hispanic, African American, or other people of color. More than 90 percent of students at Bella Romero qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. (At Frontier, 77 percent of students are white, and about 20 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.)

“When they were looking for another site away from Frontier, where does it wind up? In the Hispanic community, by the Hispanic school,” says Eric Huber, an attorney with the Sierra Club’s Environmental Law Program, one of the groups behind the lawsuit. “We think that decision was made, unfortunately, because that particular community doesn’t have the resources to fight it.”

Bella Romero Academy fourth- through eighth-grade campus.

Greeley-Evans School District 6

Hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, is the process of creating small cracks in underground rock formations using sand, water, and chemicals pumped at high pressure. The resulting fractures allow oil or natural gas to flow into a well. Fracking is a fiercely debated issue, with proponents claiming it is a valuable method for extracting resources needed for energy production, and opponents raising environmental and health concerns. More than 17 million American now live within one mile of oil and gas wells. Weld County, where Greeley sits, is one of the most fracked counties in the US, with more than 23,000 active oil and gas wells.

Despite community opposition to the project voiced in public meetings and written comments, in March 2017 the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) granted Extraction a permit for the site near Bella Romero’s fourth- through eighth-grade campus.

Shortly after, the Sierra Club, the Colorado NAACP, and environmental groups Weld Air and Water and Wall of Women filed a lawsuit against the COGCC. The suit claims the commission’s approval of the site was unlawful; the commission did not adequately address concerns about health impacts that had been raised in public comments, and failed to ensure the site was far enough away from inhabited buildings, the suit alleges. (COGCC regulations require oil and gas production facilities to be “as far as possible” from homes, schools, and other occupied buildings.)

“We have one of the largest developments proposed in Colorado within 1,000 feet of fields where middle school children play,” says Tim Estep, a clinical fellow with the University of Denver’s Environmental Law Clinic and a lawyer for the plaintiffs. “It’s not that our clients are opposed to oil and gas everywhere. In this case, it’s being done so wrong, and to a community that has already been marginalized in so many ways.” While there is no legal claim of environmental injustice, “that’s really the underlying problem in this particular case,” Estep explains.

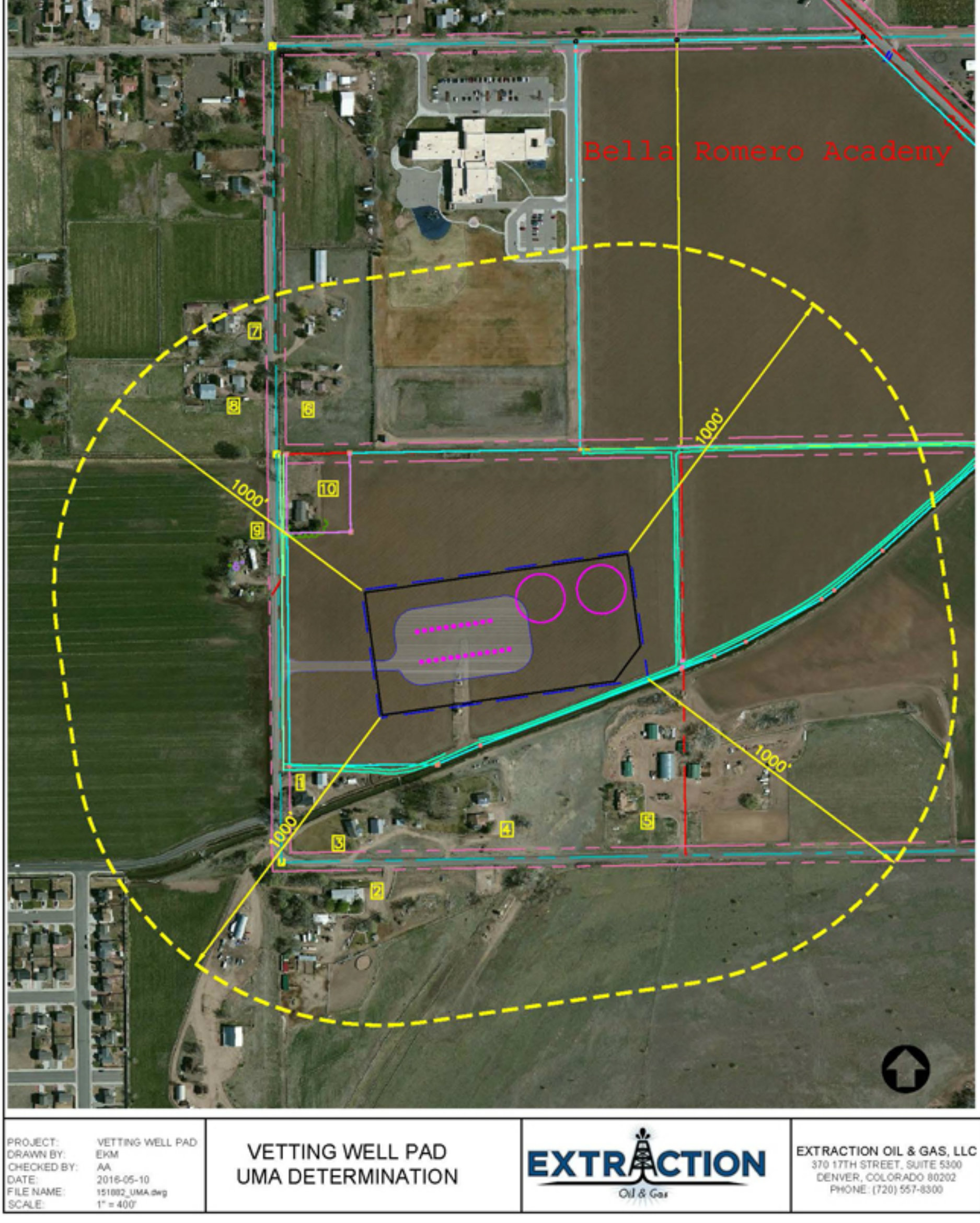

The site meets state regulations, which mandate that fracking operations be at least 500 feet away from homes and 1,000 feet away from schools. But not by much: The 24 wells will be built only 509 feet away from a home and 1,360 feet from Bella Romero. And, according to the lawsuit, Bella Romero’s playground and athletic fields sit in between the school and the proposed wells, meaning students will be playing less than 1,000 feet away from oil and gas facilities. (Extraction contended that the site is 1,250 feet from the nearest playground.)

Submission of well pad location map by Extraction Oil & Gas to COGCC (modified with Bella Romero Academy label)

Extraction Oil & Gas

Moving the proposed site from near Frontier Academy to a low-income neighborhood is a “stark disparity,” the lawsuit states, and “the Commission and operators generally experience the least amount of pushback when siting major oil and gas development in predominantly minority communities since these communities do not have the same resources as more affluent communities.”

COGCC declined to comment, citing the ongoing lawsuit. Extraction Oil and Gas did not respond to repeated requests for comment from Mother Jones. The company said in a statement in February that it plans to use “many of the innovative technologies we have introduced to our industry that ensure the minimization or elimination of impacts from construction and development, as well as increasing safety.”

There is no requirement that the state notify parents of nearby schools about approved fracking sites. Many of the Bella Romero parents didn’t know about Extraction’s plans, says Patricia Nelson, whose son, Diego, is in kindergarten at Bella Romero’s nearby kindergarten through third-grade campus. Her niece, nephew, and the children of other friends and family go to the fourth- through eighth-grade campus near where Extraction plans to build. “The whole philosophy of the school is that we are all one family,” she says. “I started going to the school board and saying, ‘You need to tell the parents what’s going on.’”

Some of Bella Romero Academy’s students come from low-income communities surrounding Greeley.

In January, the school board that oversees Bella Romero passed a resolution opposing the site. Roger DeWitt, the president of the board, said in an email that although the proposed drilling location meets state requirements, he is concerned whether the distance ensures the safety of the children from fire, explosion, and pollutants. “The product that is drawn from the ground belongs to Extraction,” he wrote. “But industrial uses are generally lousy neighbors to school zones.”

Parents and activists have held rallies protesting the development. In early March, independent protesters arrived at the construction site and draped a banner reading “People Over Pipelines” across a bulldozer. Several of the protesters were charged with trespass, and a Colorado State University student was arrested after chaining himself to the bulldozer and refusing to leave. Extraction later filed a civil lawsuit against the 23-year-old and several Jane and John Does for trespassing and interference.

Extraction aims to complete the project in 2019 and has already begun surface-level construction on the site. Earlier this month, the plaintiffs asked for a temporary restraining order on construction. But the judge quickly denied the order and indicated he would soon be ruling for the COGCC.

The plaintiffs plan to appeal if they lose. Meanwhile, Nelson is frustrated that those affected by the proposed fracking site are left in limbo. “As a parent,” she says. “I want some answers now.”