Mint Images/ZUMA

This story was originally published by High Country News and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Federal authorities at Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument are moving forward to create new plans for managing the area, despite several legal challenges to the monument’s boundaries. Conservationists say they are concerned about a rush to create new plans before the courts weigh in on the boundaries.

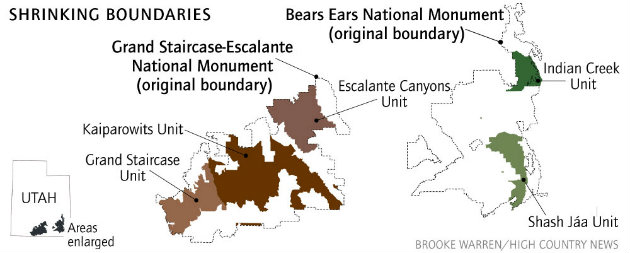

President Donald Trump last year announced he would shrink Grand Staircase-Escalante from 1.9 million acres to 1 million, dividing the Clinton-era monument into three distinct units. Trump’s proclamation stated that certain natural and archeological resources did not need protection because they were not unique to the area. Several environmental groups and tribal nations immediately filed suit to overturn the proposed changes to Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as to Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument, which Trump said he wanted to reduce by 85 percent from an Obama administration designation.

Legal experts say Trump’s reduction of the monuments is unlikely to survive scrutiny in the courts. Nevertheless, the BLM appears to be moving ahead with management plans on an expedited timeframe. At Grand Staircase, three of the BLM’s new plans correspond to Trump’s new units, called Kaiparowits, Grand Staircase and Escalante Canyon. A fourth plan will cover BLM acreage that had been a part of the Clinton designation and was removed from the monument. The Bureau of Land Management began accepting public comments in January related to the new plans; after public comment closes, the agency will produce draft plans. The public will have a chance to weigh in on those plans, once complete.

When board members of Grand Staircase Escalante Partners met with BLM Associate Monument Manager Matt Betenson in Kanab, Utah, on Feb. 16, they asked him why the BLM did not postpone the planning process until after lawsuits had played out, according to interviews with multiple people present at the meeting. “Basically his response was something very similar to, ‘Well that’s what we’ve been told to do and so we’re going to do it,’” Noel Poe, a Partners board member and former national park superintendent told High Country News. “And we got the impression that that was coming from the Department of Interior down to the BLM and down to the monument level.”

The monument’s public affairs officer, Larry Crutchfield, told HCN, “the boundaries have changed and we need to keep it moving forward.”

Grand Staircase Escalante Partners is a local group that has worked closely with federal managers for many years to organize public programming on conservation and science in the monument. Board members of the group meet with the monument manager or associate manager on a quarterly basis, and speak over the phone more frequently.

At the February meeting, board members asked Betenson how long the four new management plans would take to complete. According to three people at the meeting, Betenson said the monument managers had been instructed to have the plans finished within a year or a year and a half—a crunched timeframe for most projects of this size. “One year is very expedited,” since it took the BLM over three years for the first management plan to go through the process, said Scott Berry, a Partners board member and former attorney. “To try and redo all the work that went into that in four different flavors or variations on an expedited basis with reduced staffing and funding seems like a very difficult, verging on impossible goal to set.”

Sandstone rock formations in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Bob Wick/Bureau of Land Management

Betenson’s timeframe aligns with an August 2017 memo from Interior Department Deputy Secretary David Bernhardt instructing managers to keep their environmental analyses under the National Environmental Policy Act to one year. “In recognition of the impediments to efficient development of public and private projects that can be created by needlessly complex NEPA analysis,” Bernhardt wrote, “I am issuing this Order to enhance and modernize the Department’s NEPA process, with immediate focus on bringing even greater discipline to the documentation of the Department’s analyses and identifying opportunities to further increase efficacies.”

Grand Staircase Escalante Partners Executive Director Nicole Croft said the federal employees were instructed not to follow public comments that requested the new planning process be postponed until the lawsuits were completed.

Trump’s proclamation to alter Grand Staircase-Escalante came after Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke conducted a swift review of national monuments in 2017. Zinke held cursory meetings with supporters of the monuments, before recommending the new, shrunken boundaries. The dearth of public input harkens back to the 1996 creation of Grand Staircase itself. As Jonathan Thompson reported for HCN, “Grand Staircase-Escalante was devised so secretly, and hoisted on the public so unexpectedly, that even conservationists were miffed.”

The BLM is now planning to hold public hearings related to its new resource plans in late March, according to members of Grand Staircase Escalante Partners. The federal agency has yet to release details about the hearings. Public comments will be due 15 days after those meetings. The BLM is also moving forward with new management plans for Bears Ears National Monument. Several groups have filed suit to stop those boundary changes as well.