dhughes9/Getty

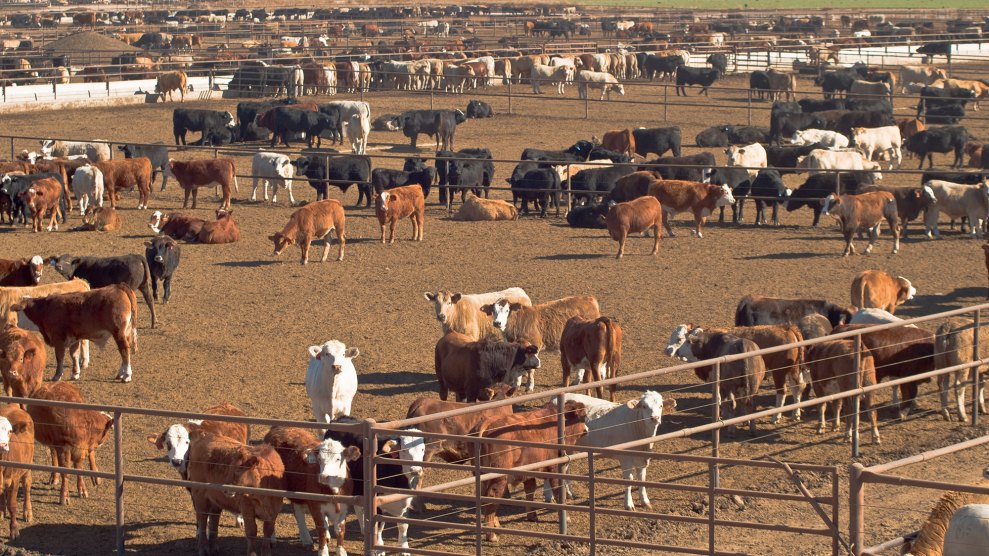

Residents of tiny Lone Jack, MO, are fighting a proposal by a local ranch to expand its feedlot from around 600 cows to nearly 7,000. It is the latest in a series of communities pushing back against a national trend toward concentrated animal agriculture.

All those cows, local opponents say, would introduce health and environmental hazards that would affect residents of the small town, which sits on the outskirts of Kansas City. The fight comes several counties in Missouri fend off concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), and as local and federal governments are considering legislation that would deregulate the agriculture industry.

Missouri has seen a rise in hog CAFOs in the past several years, says Tim Gibbons, an organizer with the Missouri Rural Crisis Center. That expansion includes several farms owned by Pipestone, a farm management company that has locations across the upper Midwest. “The cattle operation in Johnson County is sort of an anomaly,” Gibbons says. “We haven’t seen anything like that recently.”

The cattle farm, Valley Oaks, promotes its beef as “locally raised,” and has said its expansion would bring 50 to 100 jobs to the region. But Lone Jack residents say the company is pursuing a form of agriculture that will deplete the natural resources of the area. “This is not a farm,” says Karen Lux, an organizer with Lone Jack Neighbors for Responsible Farming. “This is an animal factory.”

Lux says that “there’s so many” concerns with the feedlot, including manure application, groundwater pollution, air quality and odor. Valley Oaks is proposing to raise its herd size to 6,999 animals—one animal short of the number that would require the ranch to comply with state odor regulations.

Gibbons says that the most pressing issue facing Missouri communities near large livestock farms is polluted drinking water. Many rural communities in the state rely on well water, which is susceptible to contamination from farm runoff. Communities that have high nitrate levels in their drinking water have experienced detrimental health effects, including the potentially life-threatening “blue baby” syndrome.

Water “is a big issue that goes across political ideology,” Gibbons says. “Not to mention the quality of life impacts, the air quality impacts,” and how industrial agriculture can affect “the fabric of what that smaller farming community looks like.”

One of the most vocal opponents to Valley Oaks is Powell Gardens, a 970-acre botanical garden in Lone Jack that is home to one of the largest edible gardens in the country. Powell Gardens is three miles from the proposed feedlot, and Tabitha Schmidt, the garden’s executive director, says that the feedlot raises “a lot of environmental questions.” Schmidt says it’s a “very real possibility” that if the CAFO is constructed, the resulting environmental effects could make it harder for Powell Gardens to fundraise and continue expanding its program offerings.

Schmidt said that Valley Oaks recently approached Powell Gardens to discuss a sponsorship, but the organization declined. She also said a group of Powell Gardens employees and Lone Jack residents had planned to participate in a tour of the ranch on March 16, but that Valley Oaks canceled the tour. Tony Ward, a member of the family that owns Valley Oaks, said in an email that the tour was never confirmed, and that they are still discussing possible tour dates with community members.

Ward also said that “outside groups have been spreading inaccurate information” about his family’s operation, and that they plan to build “state of the art facilities that respect both the animals we raise, as well as the air and water we all—our family included—breathe and drink.” Valley Oaks doesn’t have a perfect track record on animal treatment; in February 2017, just a few months before it submitted its CAFO proposal to Missouri’s Department of Natural Resources, the company was penalized by the Food Safety and Inspection Service for inhumane slaughtering methods.

The fight over Valley Oaks comes as several agriculture-related bills are making their way through the Missouri Legislature. One set of bills would inhibit local governments from regulating the treatment and application of fertilizer, which could expose more residents to poor waste-management practices from large farms. Another set would ban foreign ownership of farmland in the state.

Meanwhile, on the national stage, Congress is debating the Fair Agricultural Reporting Method Act, which would exempt CAFOs from reporting air emissions. And Rep. Steve King, an Iowa Republican, recently introduced a bill that would facilitate the repeal of 10 years of local agricultural regulations.

Missouri communities are fending off CAFOs across the state, including in Calloway County, Cooper County, Grundy County, and Barry County. In the latter two cases, residents initially succeeded in blocking the CAFOs through an appeal to the state’s Clean Water Commission. But shortly after commissioners voted against the CAFOs, Missouri legislators changed the makeup of the commission to favor the agriculture industry. In late 2017, Governor Eric Greitens appointed three new members to the commission, all of whom are tied to large-scale agriculture. In the commission’s next vote, the CAFOs were approved.

Elsewhere in the country, states are reckoning with the impacts of concentrated, large-scale animal agriculture. From Devil’s Lake, ND, to Des Moines, Iowa, to Dodge County, MN, both rural and urban communities are fighting to preserve water and air quality in the face of local and national deregulation of the agriculture industry.

Lone Jack residents will have an opportunity to make their case against the Valley Oaks feedlot at a public hearing on April 3. Tabitha Schmidt hopes that the Department of Natural Resources will deny Valley Oaks’ permit after listening to community testimonials. But, she says, “you hope for the best, but you always have to plan for the worst.”