Jessica Tezak/ The Evansville Courier & Press via AP

More than one-third of all men and women in the US will develop cancer during their lifetimes, but not every cancer diagnosis is an immediate death sentence. For more than two decades, the rate of Americans dying from cancer has dropped every year. However, according to an annual report from the American Cancer Society released Thursday, many young and middle-aged black Americans are not reaping equal benefits from improved cancer prevention, detection, and treatment.

“While we are making all of these advances, I think we can all recognize that we can still do a lot better,” said Dr. L. Michelle Bennett, director of the Center for Research Strategy at the National Cancer Institute, who was not involved with the report. “All of these advances are not reaching everybody equally.”

From 2014 to 2015, the U.S. cancer death rate dropped by 1.7 percent, mostly driven by decreasing death rates for lung, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers. The decline follows a trend that began in 1991, resulting in nearly 2.4 million fewer cancer deaths in the years since. The report points to several reasons behind the improving mortality rate, including reductions in smoking and advances in early detection and treatment.

Though the racial gap in cancer deaths continues to narrow as well, this mainly reflects progress for older age groups, which masks “stark persistent inequalities for young and middle-aged black Americans,” the report says. Overall, the cancer death rate in 2015 was 14 percent higher for non-Hispanic blacks than for non-Hispanic whites, down from a peak of 33 percent in 1993. Yet, while the gap narrowed to 7 percent in those 65 or older, for those younger than 65, mortality rates were 31 percent higher for blacks than for whites, with much larger disparities in many states.

The smaller gap for the older black population is partly due to universal health care access for seniors through Medicare, says Ahmedin Jemal, vice president of the Surveillance and Health Services Research Program at the American Cancer Society and a co-author on the report. On the other hand, lack of insurance among younger black Americans may contribute to their higher mortality rate compared to whites.

“We know that insurance is a gateway to accessing care,” Jemal said, and therefor improving access can reduce the racial gap. In Delaware, for example, paying for screenings and treatment for the uninsured helped to drastically reduce colorectal cancer mortality rates and shrink the gap between blacks and whites.

Researchers agree, however, that the reasons behind racial disparities in cancer deaths are multi-pronged and still not fully understood. They involve the interplay of genetics, lifestyle, and environment, as well as access to health care, Bennett said, noting “We really need more studies, large studies, that really comprehensively examine how these factors come together.”

Some states in the report, such as New York and Massachusetts, have seen the racial mortality gap disappear for whites and blacks over 65. “This is encouraging because it means messages about screening and early detection have been heard,” said Linda Goler Blount, president and CEO of the Black Women’s Health Imperative. Those shrinking gaps suggest minorities “are taking advantage of preventive services like screening mammography and colonoscopy, have reduced smoking and, for those over 65, are receiving quality care,” she said.

One area of concern exemplifying the racial mortality gap can be seen in outcomes for breast cancer. Although African-American women develop breast cancer at similar or slightly lower rates, they are more likely to die from the disease compared with white women, according to the American Cancer Society’s facts and figures on African Americans and cancer.

“Black women get breast cancer, on average, five to seven years younger than white women, so our cancers are detected later, and when they’re more advanced,” Goler Blount said. She also explained that younger black women are more likely to have an aggressive form of breast cancer known as triple negative, a much more difficult to treat subtype of cancer that develops nearly two times as often in black women. The NCI is undertaking its largest-ever study on the topic to delve into how genetic and biological factors contribute to risk.

Again, access to health care appears to play an important role. Jemal coauthored a study of women with breast cancer from 2004 to 2013 that found being uninsured accounted for more than one-third of the higher death rate for black women.

The good news, Goler Blount said, is more than 90 percent of black women are now insured following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. “If this trend continues and black women continue to be insured, have access to preventive health care and quality treatment when diagnosed with cancer,” she says, “we can expect the gap in deaths due to cancer compared with whites to decrease.”

As a whole, the new ACS report highlights that more can be done to prevent cancer in the first place, for instance by further reducing smoking, which still accounts for nearly three out of every ten cancer deaths.

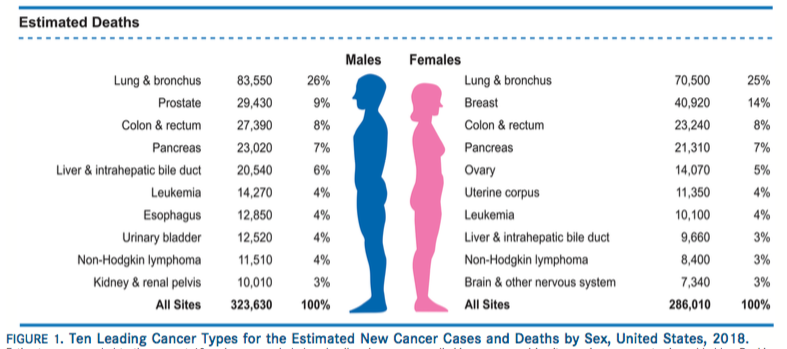

In 2018, 1,735,350 new cancer cases and 609,640 cancer deaths are projected to occur in the U.S., the report found.

“If we, the cancer community, could do a better job of implementing those things we already know work,” Bennett said, “many, many lives could be saved.”