Late last year, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the world’s largest independent conservation organization, released “Ten to Watch in 2010“, a list of endangered species facing natural and man-made threats around the world. Animals include the polar bear, the tiger, the Magellanic penguin, and the giant panda.

As it turns out, just three of the ten—the blue-fin tuna, the leatherback turtle, and the Javan rhinoceros —fall under the International Union for Conservation of Nature‘s (IUCN) category of “Critically Endangered”, one step up from “Extinct in Nature.” (The IUCN Red List is widely considered to be the standard-bearer for classifying endangered species). So why did the WWF select the critters that they did? Simply put, household names are more likely to open the hearts, and wallets, of enviro-friendly folks. According to the WWF, “Our conservation efforts are directed towards flagship species, iconic animals that provide a focus for raising awareness and stimulating action and funding for broader conservation efforts in our priority places; and footprint-impacted species whose populations are primarily threatened because of unsustainable hunting, logging or fishing.” The big and the beautiful always get the most press.

But not all conservationists are on board with such calculated efforts. One British student of zoology, who writes under the pen name “thonoir” on the blog Ninjameys, has undertaken a conservation project looking beyond what he refers to as “charismatic megafauna.” His “Endangered Species 2010“, an alternative list to the WWF’s, showcases species that few people outside of the zoology world have heard of. Thonoir is working his way up the tree of life from fungi to mammals; most recently he wrote about molluscs. While he acknowledges the WWF’s need to feature recognizable species in order to carry the most impact, and praises their “Species of the Day” project, he writes that he’d also “like to see some under-appreciated and little-known species creep onto the periphery of the public radar.”

Dracula ant (Adetomyrma venatrix)

The dracula ant is native to Madagascar, named for a unique feeding style that consists of non-lethally sucking the blood from its own larvae (termed “nondestructive cannibalism”). This species has a body somewhere between a wasp and an ant, leading some scientists to believe that the dracula ant is an evolutionary “missing link.”

Photo: April Nobile/AntWeb

Peacock tarantula (Poecilotheria metallica)

This arachnid resides in south-central India. “The [peacock tarantula’s] habitat is under intense pressure from the surrounding villages as well as from insurgents who use forest resources for their existence and operations….This species is categorized as CR [Critically Endangered] because of its range restricted to less than 100 km², single location and continuing decline in habitat quality”- IUCN Red List

Photo: Morkelsker/Wikimedia Commons

Peacock tarantula (Poecilotheria metallica)

This arachnid resides in south-central India. “The [peacock tarantula’s] habitat is under intense pressure from the surrounding villages as well as from insurgents who use forest resources for their existence and operations….This species is categorized as CR [Critically Endangered] because of its range restricted to less than 100 km², single location and continuing decline in habitat quality”- IUCN Red List

Photo: Morkelsker/Wikimedia Commons

Land lobster (Dryococelus australis)

This may be the rarest insect on the planet. First discovered on Lord Howe Island 370 miles off the coast of Australia, the land lobster was thought to be extinct by the 1920s as a result of black rats introduced to the island by shipwreck. Then in 2001, a population numbering just 24 was discovered under a single bush on Ball’s Pyramid, a small erosional remnant of a volcano. Efforts are underway to breed this large stick insect in captivity and reintroduce it to Lord Howe Island.

Photo: Peter Halasz/Wikimedia Commons

Delta green ground beetle (Elaphrus viridis)

Restricted to a 10 square mile region in Solano County, Northern California as a result of agricultural development, this ground beetle’s life cycle is dictated by the ebb and flow of vernal pools, temporary ponds of water that form from winter rains. The beetle thrives in the late winter and spring, only to go dormant underground for the summer and fall.

Photo: aneedtoknow/Wikimedia Commons

Bastard Quiver Tree (Aloe pillansii)

This succulent tree, a relative of the Aloe vera plant, grows in a desert ecoregion of South Africa and Nambia known as the Succulent Karoo. Little evidence exists that the species is successfully regenerating, believed to be due to shifting rainfall and rising temperatures as a result of climate change.

Photo: Martin Heigan/Flickr

Black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii)

Once one of the most commonly fished molluscs off the coast of California, overfishing and a bacterial disease called the Withering Syndrome have led most populations of the black abalone to decline by more than 80%, and some by as much as 99%.

Photo: Jan Delsing/Wikimedia Commons

Cromwell chafer (Prodontria lewisi)

Living only on a 200 acre reserve near Cromwell, New Zealand, this small scarab beetle faces threats from habitat degredation and predation. The reserve was the first in the world devoted solely to an invertebrate.

Photo: Bruce McKinlay/Flickr

Staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis)

In regard to this Caribbean coral species, “…there has been a population reduction exceeding 80% over the past 30 years due in particular to the effects of disease, as well as other climate change and human-related factors.” IUCN Red List

Photo: Adona9/Wikimedia Commons

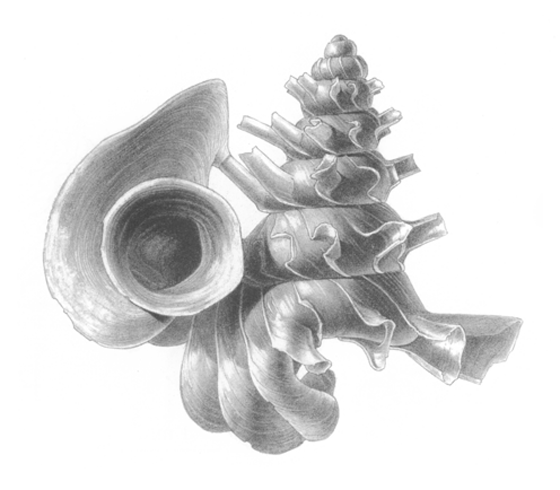

Opisthostoma mirabile

“Listed as Critically Endangered because the AOO [Area of Occupancy] is 1.5 km², with only one known locality, which has declining habitat quality due to logging in the forest and quarrying which has already lead to the loss of two subpopulations.” – IUCN Red List

Photo: Menno Schilthuizen/Wikimedia Commons

Sichuan Thuja (Thuja sutchuenensis)

This conifer was first described in 1899 by a French collector in the Sichuan Provence of China, but was not again spotted for 100 years on the clefts and ridges of a single mountain. According to the IUCN Red List, “The more accessible trees have mostly been felled for use in home building and for making various household products. The species may also have gone through a genetic bottleneck and be facing problems of inbreeding depression.”

Photo: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew/Wikimedia Commons