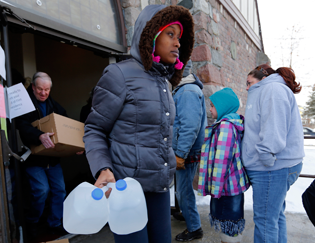

Flint residents pick up water and filters from a Red Cross center.Jim West/ZUMA

New twists emerge almost daily in the story of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, where residents were left to drink, cook, and bathe in lead-contaminated water for 17 months as city and state officials insisted the water was safe. Here’s a timeline of how things unfolded, which we’ll update as significant new details come to light.

2014

April 25: To save money, Flint changes its municipal water source to the Flint River rather than the Detroit water system. The switch is overseen by state emergency manager Darnell Earley, who, like other emergency managers around the state, is able to override local policies in the name of “fiscal responsibility.”

Summer: Residents begin complaining to local leaders about tainted, foul-smelling tap water—and health symptoms such as rashes and hair loss from drinking and bathing in it.

August/September: E. coli and coliform bacteria are found in the Flint water supply. The city instructs residents to boil tap water before drinking.

October 1: General Motors says it will stop using Flint River water in its plants after workers notice that the water corrodes engine parts.

2015

January 2: Flint issues an advisory warning that its water contains high levels of trihalomethanes, byproducts of water-disinfectant chemicals. Over time, these byproducts can cause kidney, liver, and nervous system damage. Sick and elderly people may be at risk, the advisory notes, but the water is otherwise safe to consume.

January 7: A state building in Flint starts hauling in coolers of clean water, according to emails later exposed by Progress Michigan. An email from the Department of Technology, Management, and Budget reads, “DTMB is in the process of providing a water cooler on each occupied floor, positioned near the water fountain, so you can choose which water to drink.”

January 12: Detroit offers to reconnect Flint to its water system at no cost. Emergency manager Earley rejects the offer.

January 13: Gov. Rick Snyder names Jerry Ambrose as Flint’s new emergency manager; Earley is reassigned as emergency manager for the Detroit Public Schools.

January 21: Residents show up to a town hall meeting in droves, complaining that the water is causing myriad symptoms, from rashes and hair loss to vision and memory problems.

February 3: Gov. Snyder awards Flint $2 million to improve its water system. In a memo to Snyder, state officials write, “It’s clear the nature of the threat was communicated poorly. It’s also clear that folks in Flint are concerned about other aspects of their water—taste, smell, and color being among the top complaints.”

February 18: Lead levels of 104 parts per billion are found in the tap water of LeeAnne Walters, a Flint mother of four who demanded the city test her water after her kids showed troubling symptoms. There is no “safe” level of lead, but the threshold for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to initiate an enforcement action is 15 ppb. The city offered to connect the Walters to a neighbor’s home as a short-term plan. (Read more about Walter’s fight here.)

February 25: Walters contacts Miguel Del Toral, a manager at the EPA’s Midwest water division. She informs him that Flint isn’t treating its water with standard corrosion controls—critical in an aging city like Flint—that prevent old pipes from leaching lead. Del Toral also learns that residents’ taps are being pre-flushed for several minutes prior to sampling for city water tests.

February 27: Del Toral emails aides at the EPA and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) to relay his concerns. Flushing out the pipes before testing, he writes, “provides false assurance to residents about the true lead levels.”

March 3: Follow-up city tests, also using the pre-flushing technique, find lead levels of nearly 400 ppb—27 times the EPA action threshold—in the Walters’ tap water. MDEQ blames the high lead level on the home’s internal plumbing.

March 24: Ambrose, the new emergency manager, nixes a City Council vote to “do all things necessary” to switch back to the Detroit water system, calling the vote “incomprehensible.”

March 27: Blood tests reveal that all of Walters’ four children were exposed to lead, and that Gavin, four years old, has lead poisoning.

April 6: In a Facebook post, City Council VP Wantwaz Davis accuses Gov. Snyder and emergency manager Ambrose of trying to commit “genocide” in Flint. Explaining himself to the Flint Journal, Davis says, “I feel the emergency manager and governor should be held more accountable…I do believe maybe five, maybe 10 years from now, some people are going to contract a disease…they cannot ever get rid of.”

June 24: Del Toral writes a memo (later leaked) to the head of the EPA’s drinking water division, calling Flint’s lack of corrosion controls a “major concern.”

April 28: Marc Edwards, a professor at Virginia Tech and an expert on lead corrosion, conducts new tests on the Walters’ home without flushing the taps first and finds lead levels as high as 13,200 ppb—more than twice the level the EPA classifies as hazardous waste.

April 29: The state lifts Flint’s “financial emergency” designation and Ambrose leaves the emergency manager position.

April: Del Toral writes to state aides, “Given the very high lead levels found at one home and the pre-flushing happening in Flint, I’m worried that the whole town may have much higher lead levels than the compliance results indicated.”

May 6: An EPA report identifies two more homes with high lead levels.

July 1: Susan Hedman, director of the EPA’s Midwest division, suggests that Del Toral’s report was premature and that an official version will be released “when the report has been revised and fully vetted by EPA management.” When asked for status updates by the governor, MDEQ claims the lead problem is isolated to the Walters’ home, and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MHHS) responds that seasonal elevations in lead levels are to be expected.

July 22: Snyder’s chief of staff emails officials at MHHS: “I’m frustrated by the water issue in Flint…These folks are scared and worried about the health impacts and they are basically getting blown off by us.”

August: Virginia Tech’s Edwards says he and his students will begin testing Flint’s water independently.

September 15: Edwards determines that Flint River water is 19 times as corrosive as Detroit tap water and estimates that one in six Flint homes have elevated lead levels. A MDEQ spokesman disputes the findings.

September 24: Pediatrician/researcher Mona Hanna-Attisha goes public with her research showing that the percentage of Flint children under five years old with elevated blood lead levels has doubled, and in some cases tripled, since the change in water supply. MDEQ pushes back: Spokesman Brad Wurfel calls her findings “unfortunate” in a time of “near-hysteria” among residents. “When a state with a team of 50 epidemiologists tells you you’re wrong,” Hanna-Attisha later tells the New York Times, “how can you not second-guess yourself?”

September 25: Flint issues a lead warning, advising residents to drink and cook only with cold tap water, but still maintains that the water complies with federal standards. The governor’s chief of staff emails his boss: “The MDEQ and [Department of Community Health] feel that some in Flint are taking the very sensitive issue of children’s exposure to lead and trying to turn it into a political football.”

October 2: A press release from Gov. Snyder’s office: “The water leaving Flint’s drinking water system is safe to drink, but some families with lead plumbing in their homes or service connections could experience higher levels of lead in the water that comes out of their faucets.”

October 8: Lead is found at high levels in the drinking fountains of three Flint schools. Snyder announces that Flint will go back to buying water from Detroit. The city makes the switch about a week later.

October 19: “It recently has become clear that our drinking water program staff made a mistake while working with the city of Flint,” MDEQ director Dan Wyant admits. “Simply stated, staff employed a federal protocol they believed was appropriate, and it was not.”

November 16: Lawyers announce a class-action lawsuit against city and state officials, including Snyder and Wyant, on behalf of Flint residents.

December 29: An independent task force created by Snyder to look into the crisis points fingers at MDEQ, calling its regulatory approach “minimalist” and “unacceptable.” When residents and scientists raised concerns, “The agency’s response was often one of aggressive dismissal, belittlement, and attempts to discredit these efforts and the individuals involved.” MDEQ director Wyant and spokesman Wurfel resign.

2016

?January 5: Snyder declares a state of emergency for Genesee County, home to Flint. The US Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Michigan launches an investigation into officials’ handling of the crisis.

January 7: The state’s chief medical executive advises Flint residents to use only bottled or filtered water.

January 12: Snyder deploys National Guard troops to distribute bottled water and water filters to Flint homes. A day later, the governor announces that cases of Legionnaire’s disease have spiked in Genesee County since Flint residents began drinking the river water—10 people in the county had died from the normally rare disease.

January 16: President Barack Obama declares a state of emergency in Flint, freeing up $5 million in federal relief.

January 17: Hillary Clinton brings up Flint at the Democratic debate. “I’ll tell you what, if the kids in a rich suburb of Detroit had been drinking contaminated water and being bathed in it, there would’ve been action.” Bernie Sanders goes further, saying Snyder should resign.

January 19: In a State of the State address, Snyder apologizes. “No citizen of this great state should endure this kind of catastrophe,” he says. He pledges to release his office’s emails about the Flint situation and does so the following day.

January 21: Hedman, the head of the EPA’s Midwest division, resigns. EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy announces an investigation into the division’s handling of the crisis. Obama announces that his administration will give $80 million in aid to Michigan, most of which will go towards the Flint crisis.

January 22: Snyder adamantly denies suggestions that the Flint crisis was the result of environmental racism: “I’ve made a focused effort since before I started in office to say we need to work hard to help people that have the greatest need,” he said.

January 24: The Daily Beast reveals that in 2012, Ed Kurtz, then Flint’s emergency manager, rejected using Flint River water based on conversations with MDEQ. It remains unclear why use of Flint River water was later authorized.

January 25: The state announces that Red Cross and National Guard teams have delivered bottled water to each Flint house twice, and that it will now dial back on the deliveries.

January 26: Ambrose, Flint’s former emergency manager, resigns from his position on Lansing’s Financial Health team.

January 27: A coalition of organizations and citizens, including the ACLU and Natural Resources Defense Council, file a lawsuit asking federal court to step in to provide Flint with clean drinking water.