The Rocky Fire outside Santa Rosa is the biggest wildfire in California this week.Hector Amezcua/ZUMA

On Friday, California’s wildfire season turned deadly, when Forest Service firefighter David Ruhl, 38, became the first wildland firefighter to be killed this year. Meanwhile, more than 10,000 homes are under evacuation orders as nearly 10,000 of Ruhl’s peers tackle two dozen wildfires that have scorched tens of thousands of acres across the state. As of Wednesday morning, the state’s biggest fire, the Rocky Fire north of Santa Rosa, had been burning for a week and was only 20 percent contained.

2015 has been an above-average year for wildfires in California, as the state continues to bake in an unprecedented drought. Last week Gov. Jerry Brown described his state as a “tinderbox” and declared a state of emergency. Back in the spring, conditions for wildfires were already so bad that fire ecologists were predicting a “disaster” fire season.

Summer has proved them right—to an extent. Since the beginning of the year, the number of acres burned has topped 100,000, more than twice the average of the past five years and more than burned in all of 2014. So the wildfire situation is indeed dire. But federal records show that it actually isn’t too far above the longer-term average. In other words, thanks in part to global warming, nasty fire seasons are just par for the course in California these days.

“Absolutely the drought is the biggest factor,” said Daniel Berlant, a spokesperson for Cal Fire, the state’s wildland firefighting agency. “Our vegetation hasn’t received enough water to resist wildfires. All it takes is one little spark.” (For an explanation of how climate change worsens wildfire conditions, check out the video at the bottom of this post.)

The moisture content of dead “fuel” (trees, shrubs, grasses) has been below average for most of the year across nearly the whole state, according to federal data, in a few cases dropping to the lower levels than at any time in the three decades since record-keeping began. Jeremy Sullens, a predictive wildfire analyst at the National Interagency Fire Center (a federal agency that coordinates firefighting efforts), said that there is also more fuel than normal on the ground this year. The long-term drought has caused more trees than normal to die, while at the same time a smattering of spring rain grew a fat crop of grass, he said. Those two factors combined are a perfect recipe for wildfires.

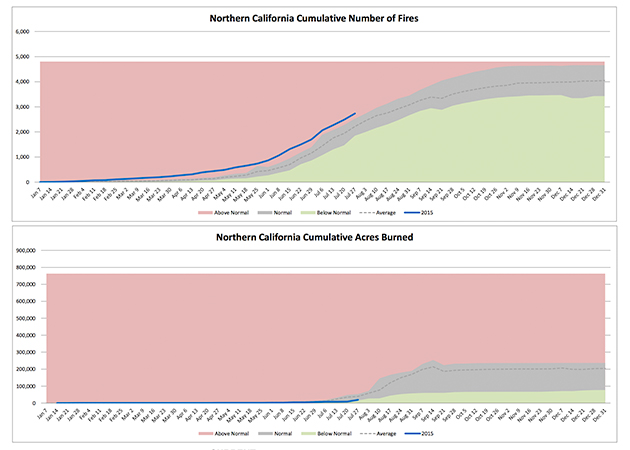

So far this year, as the following NIFC charts show, the cumulative total of fires has been just above average. Meanwhile, the total acreage of fires has been about normal. Here’s northern California:

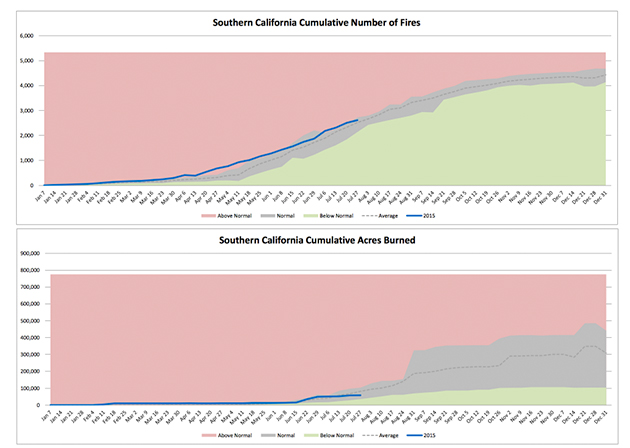

And here’s southern California:

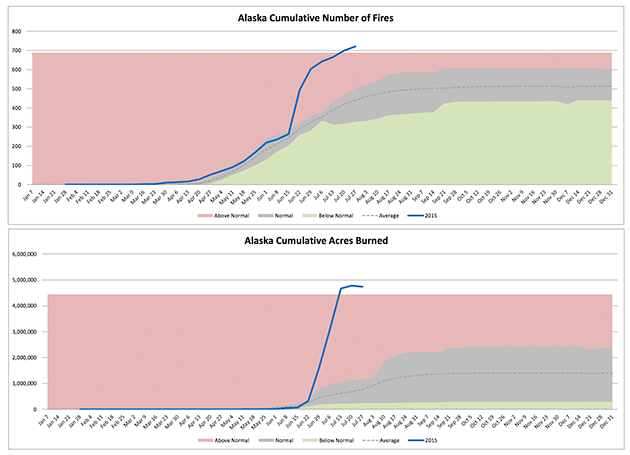

Now compare that to what’s happening in Alaska, which is truly terrifying. This could be the state’s worst fire season on record. Fires there are literally off the charts:

Back in California, the situation seems likely to improve into the fall. Sullens explained that it’s much easier to bring fire conditions back to normal—which, he stressed, does not mean no fires at all—than it is to relieve the state’s overall drought conditions. That’s because the amount of water needed to dampen potentially hazardous fuel is much less than what is needed to restock an aquifer or supply a farm. And fire managers are less concerned with season-long trends, and more focused on what the status of fuels is today and tomorrow.

“A small rain could have a huge impact on the fuel condition, even if it doesn’t have a big impact the drought condition,” Sullens said. “On a landscape level, all we’re really looking as is, ‘Is it enough to dampen the live fuels, at least for a little while?'”

That explains some differences between what scientists are projecting for the drought itself, versus for fire conditions, for the next few months.

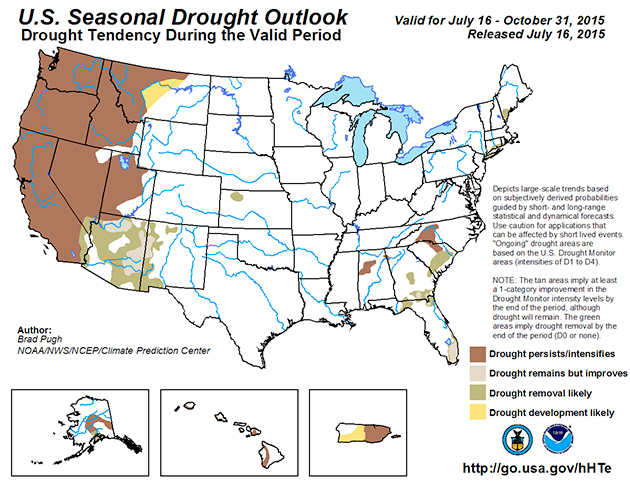

NOAA recently estimated that it would take two feet or more of rain over the next six months to lift the drought. While the strong El Niño currently gathering steam in the Pacific Ocean might send some extra rain California’s way, it’s unlikely to be that much. Here’s the most recent drought outlook from NOAA, which shows drought conditions in California persisting or getting worse through the fall:

Meanwhile, the wildfire outlook shows signs of improvement across the country. Here’s a GIF that shows the conditions from August through the fall. Bear in mind that under “normal” conditions, there will still be plenty of fires.

For the fires that do happen, will firefighters have enough water to put them out? Berlant said that although the lakes and streams that wildland firefighters source water from have been lower than normal, the agency hasn’t yet run into any situation where they had less water than they needed to do their job. Ken Frederick, a NIFC spokesperson, said that firefighters are accustomed to foregoing the luxury of a steady water supply.

“At its most basic level, wildland firefighting involves denying the fire a continuous source of heat, fuel, or oxygen,” he said. “Water can be a huge help with that task, but it can certainly be done without any water at all. And it often is.”