<a href="http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Aerosols/page3.php">NASA</a>

This story originally appeared in the Guardian and is republished here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

When American geologist Ulyana Horodyskyj set up a mini weather station at 5,800 meters on Mount Himlung, on the Nepal-Tibet border, she looked east toward Everest and was shocked. The world’s highest glacier, Khumbu, was turning visibly darker as particles of fine dust, blown by fierce winds, settled on the bright, fresh snow. “One-week-old snow was turning black and brown before my eyes,” she said.

The problem was even worse on the nearby Ngozumpa glacier, which snakes down from Cho Oyu—the world’s sixth-highest mountain. There, Horodyskyj found that so much dust had been blown on to the surface that the ability of the ice to reflect sunlight, a process known as albedo, dropped 20 percent in a single month. The dust that was darkening the brilliant whiteness of the snow was heating up in the strong sun and melting the snow and ice, she said.

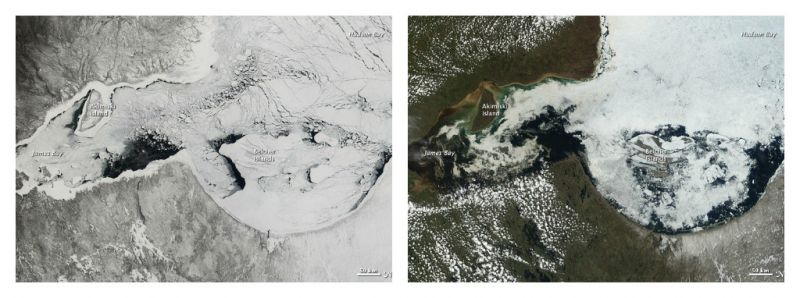

The phenomenon of “dark snow” is being recorded from the Himalayas to the Arctic as increasing amounts of dust from bare soil, soot from fires, and ultrafine particles of “black carbon” from industry and diesel engines are being whipped up and deposited sometimes thousands of miles away. The result, say scientists, is a significant dimming of the brightness of the world’s snow and icefields, leading to a longer melt season, which in turn creates feedback where more solar heat is absorbed and the melting accelerates.

In a paper in the journal Nature Geoscience, a team of French government meteorologists has reported that the Arctic ice cap, which is thought to have lost an average of 12.9 billion tonnes of ice a year between 1992 and 2010 due to general warming, may be losing an extra 27 billion tonnes a year just because of dust, potentially adding several centimeters of sea-level rise by 2100. Satellite measurements, say the authors, show that in the last 10 years the surface of Greenland’s ice sheet has considerably darkened during the melt season, which in some areas is now between 6 and 11 days longer per decade than it was 40 years ago. As glaciers retreat and the snow cover disappears earlier in the year, so larger areas of bare soil are uncovered, which increases the dust erosion, scientists suggest.

Research indicates that the Arctic’s albedo may be declining much faster than was estimated only a few years ago. Earlier this year a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported that declining Arctic albedo between 1979 and 2011 constituted 25 percent of the heating effect from carbon dioxide over the same time.

According to Danish glaciologist Jason Box, who heads the Dark Snow project to measure the effect of dust and other darkening agents on Greenland’s ice sheet, Arctic ice sheet reflectivity has been at a near record low for much of 2014. Even a minor decrease in the brightness of the ice sheet can double the average yearly rate of ice loss, seen from 1992 to 2010.

“Low reflectivity heats the snow more than normal. A dark snow cover will thus melt earlier and more intensely. A positive feedback exists for snow in which, once melting begins, the surface gets yet darker due to increased water content,” says Box on his blog. Both human-created and natural air pollutants are darkening the ice, say other scientists.

Nearly invisible particles of “black carbon” resulting from incomplete combustion of fossil fuels from diesel engines are being swept thousands of miles from industrial centers in the United States, Europe, and Southeast Asia, as is dust from Africa and the Middle East, where dust storms are becoming bigger as the land dries out, with increasingly long and deep droughts. Earlier this year dust from the Sahara was swept north for several thousands miles, smothered Britain and reached Norway.

According to Kaitlin Keegan, a researcher at Dartmouth College, the record melting in 2012 of Greenland’s northeastern ice sheet was largely a result of forest fires in Siberia and the United States.

Any reduction in albedo is a disaster, says Peter Wadhams, head of the Polar Oceans Physics Group at Cambridge University.

“Replacing an ice-covered surface, where the albedo may be 70 percent in summer, by an open-water surface with albedo less than 10 percent, causes more radiation to be absorbed by the Earth, causing an acceleration of warming,” he says. “I have calculated that the albedo change from the disappearance of the last of the summer ice in 2012 was the equivalent to the effect of all the extra carbon dioxide that we have added to the atmosphere in the last 25 years.”

Ulyana Horodyskyj, who is planning to return to the Himalayas to continue monitoring dust pollution at altitude, said she had been surprised by how bad it was.

“This is mostly manmade pollution,” she said. “Governments must act, and people must become more aware of what is happening. It needs to be looked at properly.”