Robert F. Bukaty/AP

The new poster child for climate change had his coming-out party in June 2012, when Petey the puffin chick first went live into thousands of homes and schools all over the world. The “Puffin Cam” capturing baby Petey’s every chirp had been set up on Maine’s Seal Island by Stephen Kress, “The Puffin Man,” who founded the Audubon Society’s Project Puffin in 1973. Puffins, whose orange bills and furrowed eyes make them look like penguins dressed as sad clowns, used to nest on many islands off the Maine coast, but 300 years of hunting for their meat, eggs, and feathers nearly wiped them out. Project Puffin transplanted young puffins from Newfoundland to several islands in Maine, and after years of effort the colonies were reestablished and the project became one of Audubon’s great success stories. By 2013, about 1,000 puffin pairs were nesting in Maine.

Now, thanks to a grant from the Annenberg Foundation, the Puffin Cam offered new opportunities for research and outreach. Puffin parents dote on their single chick, sheltering it in a two-foot burrow beneath rocky ledges and bringing it piles of small fish each day. Researchers would get to watch live puffin feeding behavior for the first time, and schoolkids around the world would be falling for Petey.

But Kress soon noticed that something was wrong. Puffins dine primarily on hake and herring, two teardrop-shaped fish that have always been abundant in the Gulf of Maine. But Petey’s parents brought him mostly butterfish, which are shaped more like saucers. Kress watched Petey repeatedly pick up butterfish and try to swallow them. The video is absurd and tragic, because the butterfish is wider than the little gray fluff ball, who keeps tossing his head back, trying to choke down the fish, only to drop it, shaking with the effort. Petey tries again and again, but he never manages it. For weeks, his parents kept bringing him butterfish, and he kept struggling. Eventually, he began moving less and less. On July 20, Petey expired in front of a live audience. Puffin snuff.

“When he died, there was a huge outcry from viewers,” Kress tells me. “But we thought, ‘Well, that’s nature.’ They don’t all live. It’s normal to have some chicks die.” Puffins successfully raise chicks 77 percent of the time, and Petey’s parents had a good track record; Kress assumed they were just unlucky. Then he checked the other 64 burrows he was tracking: Only 31 percent had successfully fledged. He saw dead chicks and piles of rotting butterfish everywhere. “That,” he says, “was the epiphany.”

Why would the veteran puffin parents of Maine start bringing their chicks food they couldn’t swallow? Only because they had no choice. Herring and hake had dramatically declined in the waters surrounding Seal Island, and by August, Kress had a pretty good idea why: The water was much too hot.

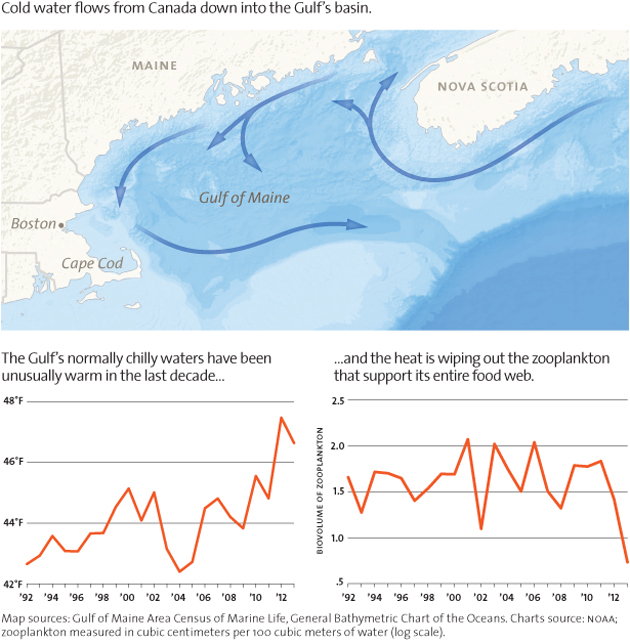

On a map, the Gulf of Maine looks like an unremarkable bulge of the North Atlantic, but it is unique. A submerged ridge between Cape Cod and the tip of Nova Scotia turns it into a nearly self-contained bowl. Warm water surging up the East Coast glances off those banks and heads for Europe, bypassing the Gulf of Maine and leaving it shockingly cold. (I’m looking at you, Old Orchard Beach!) Meanwhile, frigid, nutrient-rich water from off the coasts of Labrador and Nova Scotia feeds into the Gulf through a deep channel and gets sucked into the powerful counterclockwise currents. Whipped by that vortex, and churned by the largest tides in the world (52 feet in one bay), the Gulf of Maine acts like a giant blender, constantly whisking nutrients up off the bottom, where they generally settle. At the surface, microscopic plants called phytoplankton combine those nutrients with the sunlight of the lengthening spring days to reproduce like mad. That’s how the thick, green soup that feeds the Gulf’s food web gets made. The soup is so cold that its diversity is low, but the cold-water specialists that are adapted to it do incredibly well.

At least, they used to.

Like much of the country, the Northeast experienced the warmest March on record in 2012, and the year just stayed hot after that. Records weren’t merely shattered; they were ground into dust. Temperatures in the Gulf of Maine, which has been warming faster than almost any other marine environment on Earth, shot far higher than anyone had ever recorded, and the place’s personality changed. The spring bloom of phytoplankton occurred exceptionally early, before most animals were ready to take advantage of it. Lobsters shifted toward shore a month ahead of schedule, leading to record landings and the lowest prices in 18 years.

Hake and herring, meanwhile, got the hell out of Dodge, heading for cooler waters. In all, at least 14 Gulf of Maine fish species have been shifting northward or deeper in search of relief. That left the puffins little to feed their chicks except butterfish, a more southerly species that has recently proliferated in the Gulf. Butterfish have also been growing larger during the past few years of intense warmth, and that, thinks Stephen Kress, might be a key. “Fish start growing in response to changes in water temperature and food,” he says. “The earlier that cycle starts, the bigger they’re gonna be. What seems to have happened in 2012 is that the butterfish got a head start on the puffins. If it was a little smaller, the butterfish might actually be a fine meal for a puffin chick. But if it’s too big, then it’s just the opposite. That’s one of the interesting things about climate change. It’s the slight nuances that can have huge effects on species.”

Life would go on without puffins. Unfortunately, these clowns of the sea seem to be the canaries in the western Atlantic coal mine. Their decline is an ominous sign in a system that supports everything from the last 400 North Atlantic right whales to the $2 billion lobster industry.

The next sign of deep weirdness arrived in December 2012, when Florida beachcombers began spotting hundreds of what appeared to be penguins soaring above the Miami surf. They turned out to be razorbills, close relatives of puffins that also call the Gulf of Maine home.

Razorbills should be high on your reincarnation wish list. Superb fliers, they can also plunge into the sea and pursue fish underwater by flapping their wings—while dressed in black tie. James Bond, eat your heart out.

But normally, they do all this in the North Atlantic. Suddenly thousands of them had decided to move to Florida. The consensus was that they had simply kept going in a desperate attempt to find food—and that it couldn’t end well for them. It didn’t. By early 2013, hundreds of dead razorbills had washed up along East Coast beaches, most emaciated. So did 40 puffins. “That’s very rare,” Kress says. In fact, finding even a single dead puffin on the beach is unusual. “They’re tough little guys! They’ll live 30 years or more.”

The weirdness continued. In the spring of 2013, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration made its semiannual trawl survey of the Gulf of Maine, dragging a net at dozens of points throughout the Gulf and counting, weighing, and measuring everything caught. There were plenty of butterfish and mountains of spiny dogfish, a small shark that used to be relatively rare in the Gulf of Maine but now owns the place. There were very few cod, the fish that made New England, that lured thousands of fishing boats from Europe, that fed millions of people over the centuries. NOAA slashed the 2013 quota for cod to a pittance, putting hundreds of enraged fishermen out of work.

In recent history, the average ocean surface temperature of the Gulf of Maine has hovered around 44 degrees Fahrenheit. 2013 was the second-warmest year in the Gulf in three decades, with an average surface temperature of 46.6 degrees. But it was nowhere near the freakish spike to 47.5 degrees in 2012, and the phytoplankton did not repeat its crazy early bloom. Instead, it didn’t bloom at all. “So poorly developed, its extent was below detection limits” was how NOAA put it in its Ecosystem Advisory, sounding surprisingly calm, considering it was saying the marine equivalent of “No grass sprouted in New England this year.” Phytoplankton feeds some tiny fish and shrimp directly, but more often it feeds zooplankton, the bugs of the sea, and these in turn feed everything from herring to whales. The undetectable phytoplankton bloom did not bode well for zooplankton, and sure enough, that spring NOAA broke the grim news: “The biomass of zooplankton was the lowest on record.” Even this dirge doesn’t do justice to the dramatic deviation from the organisms’ historical norm: Their numbers bounced along in a comfortable range for 35 years before taking a gut-wrenching nosedive in 2013.

By the time of that announcement, Project Puffin was starting its 2013 season. With spring temperatures closer to normal, Kress had hoped that his Seal Island puffins would return to their fruitful ways, but only two-thirds of the colony showed up. Still, a new chick was chosen for the Puffin Cam feed, and viewers named her Hope. For a while, all went well. Kress saw fewer butterfish being delivered, and Hope flourished. But soon Kress noticed that fewer birds than usual were hanging out at the Loafing Ledge, a rocky ridge where the parents socialize between feedings. Then he realized that the time between chick feedings was considerably longer than normal. The puffins were having to range much farther to find fish.

Too far, as it turned out. Although Hope successfully fledged on August 21, she was one of the few lucky ones. Only 10 percent of the puffin chicks survived in 2013—the worst year on record. “We’ve never seen two down years like this,” Kress told me. “The puffins really tanked.”

And how could they not? The Gulf of Maine, the great food processor of the western Atlantic, was almost out of food.

Usually, a system as large and complex as the Gulf of Maine, sloshing with natural noise and randomness, will disappoint any human desire to fit it into a tidy narrative. It can take years to tease a clear trend out of the data. But by late 2013, things were so skewed that you could see the canaries dropping everywhere you looked.

November 30: Researchers announced that instead of the dozens of endangered right whales they normally spot in the Gulf of Maine during their fall aerial survey, they had spotted…one. They were quick to note that the whales couldn’t all be dead, just missing—probably off in search of food. Sure enough, in January 2014, 12 of the same species of whale were spotted in Cape Cod Bay, where food is more plentiful.

By now, you’ll have no trouble filling in this sentence from the December 4 Portland Press Herald: “This summer, a survey indicated that the northern shrimp stock was at its ____ ____ since the annual trawl survey began in 1984.” That’s right: lowest level. In fact, the sweet Gulf of Maine shrimp—a closely guarded secret in New England—had collapsed so completely that regulators closed the 2014 season and warned of “little prospect of recovery in the near future.” It takes shrimp four to five years to reach harvest size, and few of the shrimp born in the Gulf of Maine since 2009 have survived. If shrimp miraculously produce a bumper crop this year, there might be a few to eat in 2018. In the meantime, throw some butterfish on the barbie.

Or maybe sailfish or cobia, two Florida species hooked by bewildered New England anglers in 2013. The Gulf of Maine Research Institute scrambled to find a bright side, publishing a paper (PDF) on the commercial potential of former Virginia standbys like black sea bass, longfin squid, and scup, which are new regulars in the Gulf. Admirable adaptability, and undoubtedly a few quick-moving fishermen will profit from the regime change. But I don’t relish life in a world where only the hyperadapters survive.

“A puffin is an excellent example of a specialist bird that is going to be vulnerable to climate change,” Kress says. “For a specialist bird like a warbler or a seabird, which relies on a small range of foods but lives in a vast area, if something goes wrong anywhere in the migratory range of that bird, it’s in big trouble. And its ability to adapt is less than a bird with a more generalist lifestyle like a gull or a crow. Those highly adaptive birds are going to have the advantage in the long run. We see that vividly with the pictures of Petey trying to wolf down that oversized butterfish. It’s scary. But it’s a glimpse into a possible future.”

Or present. We tend to think of climate change as incremental and inexorable, like seeing old friends age at the annual reunion. There are some new wrinkles, a step has been lost, and you know there’s no going back, but at least you can still look forward to years of friendship. But ecosystems are wired with tipping points. A tweak here and there can make things unrecognizable tomorrow. Glaciers melt. Forests ignite. And suddenly your old pal isn’t answering her phone anymore.

Yes, we can adapt. Us and the gulls and the rats. But it will be awfully lonely out there.

For 40 years, Stephen Kress has traveled to the same Maine islands each spring, has watched the same puffin couples return year after year to raise their chicks. Now he doesn’t know what to think. “I’ve seen colonies go up and down, and I know one year doesn’t make a pattern, but you can’t help but wonder. We’ve worked decades to build those populations up, and in 2013 we lost a third. That’s pretty dramatic.”

Still, Kress, who calls himself a perennial optimist (“Who else would start Project Puffin?”), will head back out this May, on the heels of this winter’s cold snap. He plans to outfit a few birds with GPS devices in hopes of finding the key places where they feed and overwinter. Perhaps there are new refuges to be found, places just a little colder or more resilient, where a puffin can still be a puffin. In May, the Puffin Cam will go live, a new chick will get a new name, and a fresh batch of schoolkids will tune in to get a look at their brave new world.

Update: The Puffin Cam is now live and embedded below. Petey’s parents laid a new egg on May 16, which is a normal egg date and a promising start to the season.

Project Puffin‘s live cam.