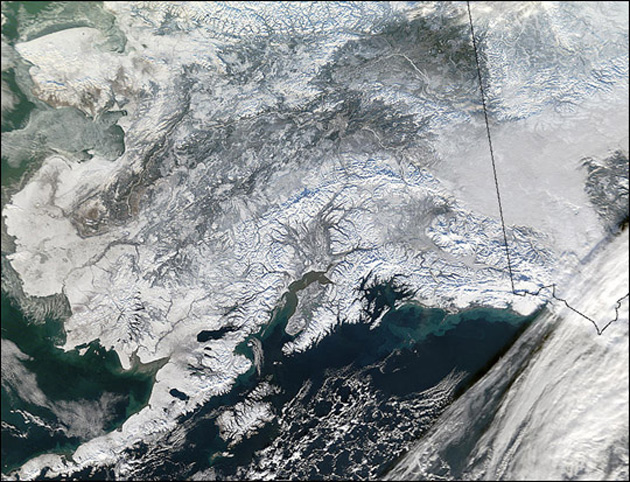

Newtok Flood, September 22, 2005<a href="http://commerce.alaska.gov/dnn/dcra/PlanningLandManagement/NewtokPlanningGroup/NewtokVillageRelocationHistory/NewtokHistoryPartThree.aspx">Stanley Tom</a>/Alaska Division of Community and Regional Affairs

This story first appeared on the Guardian website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

An Alaskan village’s quest to move to higher ground and avoid being drowned by climate change has sputtered to a halt, the Guardian has learned.

Newtok, on the Bering Sea coast, is sinking and the highest point in the village—the school, which sits perched atop 20-foot pilings—could be underwater by 2017. But the village’s relocation effort broke down this summer because of an internal political conflict and a freeze on government funds.

The Guardian wrote about the strains placed on Newtok by the erosion which is tearing away at the land, and at the villagers’ efforts to move to a new site, known as Mertarvik, in an interactive series in May.

Those tensions fed a rebellion against the village leadership, the Newtok Traditional Council, which had run the village for seven years without facing an election, and the administrator overseeing the relocation effort, Stanley Tom. His critics said he had botched the move to Mertarvik, and neglected the existing village.

Since October, Newtok residents voted repeatedly to elect a new roster of candidates to the council. They also tried to remove Tom. But the council refused to recognize the results, and Tom refused to step aside.

In July, the Bureau of Indian Affairs took the unusual step of intervening in the internal dispute, and ruled the old council—which was working closely with Tom—no longer represented the villagers of Newtok. In a July 11 letter, Eufrona O’Neill, acting regional director of the BIA, noted the agency generally did not intervene in tribal political conflicts.

But she said the standoff put the village at risk: “The continuation of a leadership vacuum would be detrimental to the best interests of the tribe, particularly in the present circumstances, where the community is in the midst of trying to physically relocate to a new village site due to serious erosion occurring at the present site.”

O’Neill noted the confusion could freeze funds for the village, as government agencies withhold funds if there are doubts about lawful signing authority. She went on to determine that the BIA now recognized the new council, which had challenged Tom’s authority. Tom said in a telephone interview he would appeal the ruling—ensuring the political standoff continues.

The long stalemate has cost the village several months in its efforts to relocate, Tom said. “Everything is kind of frozen right now,” he said. “We’ve had a pretty big setback.” Other relocations efforts were also on hold for unrelated causes.

The internal dispute exposed the severe strain on native Alaskan villages—such as Newtok—in dealing with the effects of climate change. Some 186 native Alaskan villages—or 86 percent of all native communities in Alaska—are threatened by climate change, a federal government report found.

Many villages, like Newtok, are losing land to erosion. The Ninglick River, which encircles Newtok, is eating the land out from under the village. Others are sinking in the melting permafrost. A handful have started the process of relocation. But none had gone as far as Newtok in finding a new site and beginning the slow and laborious process of negotiating through the web of state agencies to find funds for their relocation.

Robin Bronen, a human rights lawyer in Anchorage, has argued extensively that the federal government’s failure to recognize slow-moving climate threats as disasters leaves such communities stranded, with no clear set of guidelines—or designated funds—to secure their communities in place, or plan a move.

Now even Newtok’s relocation effort is in trouble. Amid the funding delays and political crisis, Newtok did not take on any new building work—leaving the 350 residents with no place to go when the waters come in. It was the second year in a row the village was forced to cancel planned construction. In 2012, a barge laden with materials for a road project undertaken by the military ran aground—shutting down construction for the year.

Tom had said at the start of the year that he hoped 2013 would bring a burst of construction at the new site. He had initially hoped to use more than $4 million in Alaskan state government funds to bring in heavy equipment to quarry rock and to build housing for the villages. Tom also said he was hoping to complete a detailed planning survey.

There were plans also to complete the largest planned structure for the new village—an evacuation center designed to provide shelter to all of Newtok’s residents in the event of a severe storm. The evacuation center now consists of a simple concrete platform. But the funds were not released, and Tom’s determination to contest the BIA decision suggests the standoff could continue.