Activist Carrie Hahn explains the potential risks of the natural gas drilling technique known as fracking to one of her Amish neighbors. OnEarth/Lynn Johnson

This story was originally published on the website of OnEarth magazine.

A bleak December sky hangs low over rural Lawrence County, Pennsylvania. Here, in areas populated by large Amish families, open fields roll toward the horizon uninterrupted by electrical wires and telephone poles. Stepping from a car that seems grossly out of place in this 19th-century landscape, Carrie Hahn, a newcomer to the area, takes a deep breath of mud and cow outside an Amish farmhouse. Suddenly, like an apparition, Andy Miller appears on a flagstone path, his face hidden beneath beard and broad-brimmed hat. He quickly ushers us inside a large, unfurnished mudroom to escape the wind.

Miller, who is in his late 40s and has nine children, is a leading member of the Old Order Amish, who eschew all modern conveniences. (Like all the Amish names in this story, Miller’s has been changed at his request, to respect Amish traditions and preserve his anonymity.) Standing against a western window, a silhouette of felt hat, bushy sideburns, and stiff cotton work clothes, he explains how he came to be in the uncomfortable position in which he finds himself today: dealing with multibillion-dollar energy companies that use high-tech methods to shatter the earth and release mile-deep pockets of natural gas.

Decades ago, Miller says, oil and gas companies began prowling around western Pennsylvania, locking residents into leases for conventional gas wells, which are relatively shallow and unobtrusive. Many landowners had no idea that once they had assigned their mineral rights, often for a thousand times less than the going rate, the leaseholders could return and burrow deeper into the same piece of property.

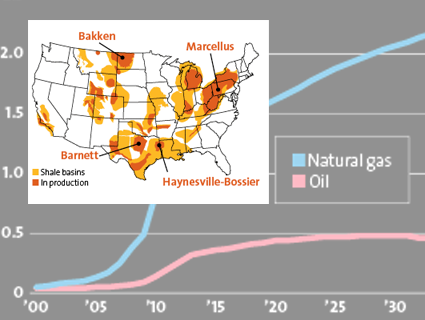

This time around the gas companies intend to drill into the Marcellus Shale—a 400-million-year-old, mile-deep formation that sweeps from West Virginia, across Pennsylvania, and into New York—then turn their bits horizontally and continue boring for another couple thousand feet. Wells are then injected with millions of gallons of highly pressurized water laced with sand and chemicals; the solution fractures the shale and releases pockets of natural gas. This is fracking.

Miller sold his mineral rights to a company called Atlas, which was bought by Chevron in 2011. “The money helped,” he says, “but I wished I knew more of what to expect.” Now, thanks to people like Carrie Hahn, Miller understands that producing gas in this manner is no simple matter. Over a period of months, workers carve a multi-acre drilling platform out of forest or field, then cram it with mixing tanks, storage tanks, compressors, gas pipes, flaring towers, diesel generators, office trailers, and porta-potties. Nearby, they dig plastic-lined ponds of several acres to hold either freshwater or “produced” water that flows up and out of the wells. During development of the site, trucks carrying water, chemicals, sand, and other equipment come and go—up to 1,000 of them a day.

“We don’t want huge gas companies coming here because of the heavy pollution, the traffic, and so much money,” Miller says. “When money rules, a lot of bad things happen to a community.” But good things have happened, too. With his payout from Atlas, Miller installed new drainage tiles to reduce excess water in his fields (yes, using only horse power). Other Amish families in the area have used gas royalties to build greenhouses or sawmills. “Buildings have to be kept up,” Miller says, shrugging. “But we would have survived without the money, somehow.”

Since the shallow well went in, Miller has managed to keep energy companies off his property, despite his lease. He gave an earful to a representative who tried to get near his well on a Sunday, and he continues to refuse access to a Texan seeking to seismically map his land (Miller has no obligation to permit this testing). I press Miller, who is now invisible to us in the darkness, to explain how he can legally stop a company from fracking if it owns the mineral rights on his property, but he deflects my inquiries. “It’s time for the community to take a stand,” he mutters enigmatically. When his wife, in a long skirt and a bonnet, lights a kerosene lantern and places dinner on the kitchen table, Hahn and I know it’s time to leave.

FOUR HUNDRED OLD ORDER AMISH families live in and around Lawrence County’s borough of New Wilmington. Extended families live in plain white houses—no shrubs, no shutters—surrounded by gardens, barns, farm fields, and long stringers of ever-flapping laundry. Horses, cows, and sheep graze on rolling pastures; horses and buggies deliver children to one- or two-room schoolhouses served by an outhouse and an outdoor water pump. Old Order Amish don’t use cars or phones, electricity from the grid, indoor toilets, or upholstered furniture. Many live off their land; some run small businesses. Wooden signs at the ends of driveways advertise their wares: rocking chairs, maple syrup, eggs, fudge, donuts, firewood, sawdust, and fresh produce.

Soon, however, customers—including the thousands of international tourists who visit the Amish countryside each year—may be chased away from this homegrown bounty as New Wilmington, like other communities before it, is transformed by the industrial frenzy of shale-gas extraction.

As work crews have moved into the area, gas stations, lunch counters, coffee shops, the local hotel, and a tanning salon (favored by the wives of imported workers) have profited. Large landholders have done well, too, receiving up to $3,500 an acre for their mineral rights. “We’ve got some wealthy people now,” says New Wilmington Mayor Wendell Wagner. “Investment advisers and lawyers are advertising their services.”

But the town is seeing more friction, too, between landowners who trust energy companies to do the right thing and neighbors—sometimes even family members—convinced industry will cut corners and ravage the countryside. (Atlas Energy, which has leased mineral rights on several Lawrence County properties, including Miller’s farm, would not comment for this story.) “I’ve been to town meetings and seen pictures of what’s going on,” says Ivan Dubransky, 64, who grew up in the area and worked for Pennsylvania Power and Light. “We’re in the same situation now that Washington County was three years ago. Back then, a lawyer told us fracking was the best thing that had ever happened down there, and that we’d better sign up. He came back recently and said it was the worst thing that had ever happened to his county.”

These are familiar concerns and conflicts, even supplying the plot for the new Matt Damon movie Promised Land. But in the small towns of western Pennsylvania, where many landowners have zero control over the fate of hydrocarbons beneath their property, the battle lines can be oddly mutable, and the Amish, many of whom have been rooted to this landscape for more than five generations, now find themselves in deeply unfamiliar territory.

LUCKILY FOR HER AMISH NEIGHBORS, Carrie Hahn, 47, is adept with a smartphone. She knows her way around county records and has no problem challenging corporate or local authority. With her husband, Bill, and their two horseback-riding, soccer-playing teenage daughters, she moved here from Pittsburgh nearly two years ago, seeking a healthier lifestyle and room to start a market garden. (A registered Republican, Hahn also works as a nutrition advocate for the Weston A. Price Foundation, which promotes a diet centered on fresh produce and animal products.)

The Hahns spent considerable time searching for property in the area, but an uptick in oil-and-gas drilling had tripled the price of land that included subsurface mineral rights. The Hahns could see that drilling would soon be a part of their daily life, so they started digging into what that might mean.

“I spent hours every day, researching, and reading anything and everything I could find on the environmental, financial, and social impacts of fracking,” Carrie Hahn says. “Soon, we were looking for land anywhere the shale was not.”

This was physically impossible if the family wanted to stay in western Pennsylvania, but the Hahns decided that controlling the rights to minerals beneath their home would be the key to minimizing their exposure. Thousands of leases have already been signed in Lawrence County, although only 26 wells destined for hydrofracking had been drilled as of June 2012. Residents are looking warily toward Washington County, to the south, which has 896 deep wells, and Bradford County, to the east, which has 1,795. According to estimates by Terry Engelder, a Penn State geoscientist, the Marcellus shale formation might contain enough technically recoverable natural gas to supply the entire United States, at the current rate of use, for up to 20 years.

The Hahns eventually purchased a modest house on 14 acres, and they continue to turn down offers from landmen seeking to purchase their mineral rights. But the couple knows that holding out will do little good if a deep well is drilled on the 100-acre property across the street, where rights have already been leased to Atlas Energy. “That would be the end of my organic farm,” Hahn says.

But she hasn’t given up hope. Before Atlas can sink a well on that property, it needs to piece together rights to hundreds more acres to make its investment worthwhile, which means the company is pursuing mineral rights from some of the Hahns’ Amish neighbors. And that’s why Carrie now spends her days going door to door with rolled-up property maps, standing on wind-whipped porches and in dimly lit vestibules, respectfully explaining the risks of hydraulic fracturing to a community that, because of its religious convictions, is largely immune to both the cries of energy independence that rally fracking supporters and to the consumer opportunities that fracking windfalls might put within their reach.

THE NEXT MORNING, Hahn introduces me to Seth Bender, a sprightly farrier, 35 years old and the father of six. “I’m against the drilling because I live here,” he says as he bangs a horseshoe against an anvil in a drafty barn. “I’ve heard about the sinkholes and the earthquakes. I’m too much of a land lover to favor drilling. I want to keep the land the way God made it.” Bender’s Amish neighbors leased their land, “but I don’t think they’d have signed if they had it to do over again,” he says. “People here think, ‘If everyone’s done it, then so will I.'” He rasps the hoof of a bay mare, muddy in her harness. “Lots of people said they wouldn’t drill, because it’s against the elders, the rules. But they signed anyway and don’t talk about it. That two-sided thing used to be against our teaching.”

He drops the hoof. “This friction is caused by greed. Scripture says that at the end of times, it will take over. I could have been engulfed in it, too: we all like to make money. But I was taught at home that money not worked for”—money from leasing, that is—”is no good.”

The prospect of deep drilling has strained relationships not just among the Amish. “My cousin wanted no part of this, but his wife and kids did,” Ivan Dubransky, the former power company worker, tells me. “He ended up signing, but now he won’t even talk to me about it.”

“I went on the township’s Facebook page to ask questions about the seismic testing near me, and someone told me to go chain myself to a tractor,” says Suzanne Matteo, a local resident who now travels to distant post offices to avoid her pro-fracking local postmistress.

IT’S TEMPTING TO THINK of the Amish as low-carbon innocents, the last people on earth who would knowingly invite oil and gas companies to intrude upon the land that sustains them. And the sight of wooden buggies parked near chemical tankers does spark some cognitive dissonance (as does learning that some Amish feel animosity toward energy companies only because they settled for $3 an acre, instead of $3,000).

But “the Amish are capitalists,” says Erik Wesner, a former scholar of Anabaptism who founded the website Amish America, which examines Amish culture and communities across North America. They’re astute businesspeople, Wesner continues, and “they make individual decisions, so long as they don’t go against their Ordnung,” or rules and standards.

Besides, the Amish have to pay taxes like anyone else, and farming has never been lucrative. They say the wells, as presented by the gas companies, seemed innocuous. According to Hahn, the technological isolation of the Amish can make them easy marks: “They don’t have televisions or the internet, so they can’t learn about fracking or even see if the landmen are lying when they say their neighbors have leased and that they could make a lot of money.”

Landmen even brandish maps, Hahn adds, with plots falsely marked as leased. Dubransky says that landmen tried fooling him, as well. “I had a kid tell me I’d have more protection [against other drillers] if I signed a lease than if I didn’t,” he says, incredulous. (Pennsylvania law doesn’t allow energy companies to drill under non-leased property, so by not signing a lease, Dubransky kept his land protected.)

With other concerned community members, Hahn last year formed the Fracking Truth Alliance of Lawrence and Mercer Counties, which hosts forums to raise awareness about oil and gas development. Amish men have come to several of these, Hahn says. The group fought, unsuccessfully, to prevent the Wilmington Area School Board from leasing district-owned land to an energy company. And it’s currently trying to raise money to help Amish families test their water before deeper drilling and fracking begin. Without such baseline data on pre-drilling conditions, it’s impossible to win a lawsuit should water later become polluted.

“It costs $1,200 for a Tier 3 test, which is the broadest spectrum,” Hahn says. “But many of these families live below the poverty level.” (The Penn State Cooperative Extension Service recommends twice-a-year testing for the next 30 years if there is drilling and fracking activity near your house to monitor any potential pollution. Pricing may vary.)

The Amish worry about water quality for themselves, for their livestock and their gardens; they also worry about heavy traffic, which could shatter the carefully cultivated tranquility of their daily rhythms. There are reports, in other fracked counties, of well-servicing trucks running horses and buggies off the road. In Minnesota, an Amish family is fighting a rail yard that will wash and load fracking sand, on the grounds that the noise and traffic may prevent them from practicing their religion. Constitutional issues aside, their legal action is noteworthy because the Amish way is to resist quietly, if at all.

ONE AFTERNOON, I ACCOMPANY Hahn as she makes a cold call on Fred Kingery, the financier who owns the vacant 100 acres across from her house. In the double-height living room of his large stone house, a gas fire glows in the grate and nautical paintings decorate the walls. Kingery explains his pro-drilling position, which is based on a belief that the burning of hydrocarbons isn’t warming the planet, and that Marcellus gas will free the nation from dealing with its political enemies.

Hahn interrupts. “I’m screwed if you do a platform across from my house.”

“I wouldn’t want one across from my house either,” Kingery concedes. “But that’s just how it is.”

Hahn frowns, and Kingery adds, “It’s not about the money. It’s all about energy independence.”

“It’s constant noise and high-voltage lights.”

“It’s not forever,” Kingery sighs. “These issues come with progress. It’s part of the process, whether it’s the railroads or building skyscrapers.” Hahn realizes she’s getting nowhere. She asks Kingery if he tried to persuade her neighbors to allow seismic testing on their property.

“No,” he says. “I wasn’t trying to talk them into it. But I spoke to them about it because I thought it would be in their best interest.”

A FEW SHEEP-DAPPLED MILES AWAY, a drilling rig towers 150 feet above a soybean field behind Sam and Lydia Mullet’s farmhouse. The drill pad sits on land owned by Dorothy Hurtt, an elderly “English” woman—as the non-Amish are known—from whom the Mullets bought their property 18 years ago. The steady thud of drilling, which has gone on round the clock for several weeks, makes normal outdoor conversation impossible. The Mullets have nine children; the family subsists off its extensive garden (a strawberry patch produces 200 quarts a day at its peak), fees from training carthorses for others, and sales of the bentwood rockers that Sam Mullet crafts in a workshop behind the house. Asked how the drilling has affected her, Lydia answers in a tremulous voice. “I’m depressed about it, but we feel helpless because it’s not on our land. And the lights shine through our windows at night. It’s not relaxing.” Since the work began, Lydia has been waking at 3 a.m., unable to go back to sleep.

“I just hope it turns out good in the end,” Sam says. “My attitude is live and let live, as long as it’s not hurting the earth. We try to avoid conflict.”

The Mullets’ 3-year-old son, bright-eyed under his broad-brimmed hat, skips about his father’s workshop with a length of strapping and motions for his visitors to peep inside a cardboard box, where five yam-sized puppies squirm. “I don’t want your kids outside breathing that silica dust once they start fracking,” Hahn says to Lydia.

“Okay,” Lydia answers, diffidently. “I think they’re going to be done here in another week or so.”

“They’re just doing the first well now,” Hahn tells her. “You know they could put 12 wells on that platform?” Lydia’s face goes ashen. She looks shocked. She had no idea that the pounding could continue for several more months.

If the drilling and fracking weren’t temporary, Sam tells Hahn, he’d likely move away. Perhaps this is possible: the Amish own thousands of acres throughout Lawrence and Mercer Counties. But a new address is no guarantee that drilling won’t intrude—the Marcellus underlies a vast area, and neither water nor air pollution stick to property lines.

I ask Mullet if his community would ever take a unified stand against this sort of activity, as Andy Miller had hinted they might. He shakes his head and answers slowly. “We don’t want to go to court, to testify about water problems. But we’re glad for people like Carrie to do this.” Mullet’s voice trails off. Then he repeats, in a tone halfway between resolved and resigned, “We try to avoid conflict.”

Hahn smiles weakly. She feels deep empathy for families like the Mullets, who are stressed and sickened by the drilling activity nearby and are living, she says, in constant fear and worry. “If something goes wrong here,” she asks, “who’s going to help you? The government? I don’t think so.”

After her confrontation with Kingery, Hahn is hopeful that he won’t allow Atlas to put a drilling platform near her house, should the company eventually piece together the acreage it needs. But she still worries that a well within a few miles of her property could affect the food she plans to grow. And so for her own family’s sake, as well as the sake of her Amish neighbors, she continues to pull together community forums, to take water samples around the county, to talk to her new neighbors and prepare them for what’s coming—and what’s at stake.

“We want the industry to know that we are out there,” she says. “We want them to know that we’re watching what they’re doing, and that they can’t just come in here and sandbag us.”