<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-59438263/stock-photo-young-woman-at-laying-on-solarium-bed-and-get-brown-skin-tone-ready-for-summer.html?src=2e69852496e006e4153e45f3c910d33e-2-49">.shock</a>/Shutterstock

A doctor in a white lab coat stands at the pearly gates. The voice of God booms, “And your good deeds?” The man responds, “Well, as a dermatologist, I’ve been warning people that sunlight will kill them and that it is as deadly as smoking.”

His smug smile fades as God snaps, “You’re saying that sunlight, which I created to keep you alive, give you vitamin D, and make you feel good, is deadly? And the millions of dollars you received from chemical sunscreen companies had nothing do with your blasphemy?”

A bottle of SPF 1,000 sunscreen materializes in the dermatologist’s hand. “You’ll need that where you’re going,” God says.

The scene is part of a training video* for tanning salon employees made by the International Smart Tan Network, an industry group. The tone is tongue-in-cheek, but it’s part of a defiant campaign to defend the $4.9 billion industry against mounting evidence of its questionable business practices and the harm caused by tanning. And, in an extraordinary touch, it is portraying doctors and other health authorities as the true villains—trying to counter a broad consensus among medical authorities that sunbed use increases the risk of skin cancer including melanoma, the most lethal form.

To sway public opinion, the industry is drawing on its vast network of outlets; there are more tanning salons in the United States than McDonald’s. Some salon operators are putting trainees through a “D-Angel Empowerment Training” program that uses the video, which was purchased by FairWarning through Smart Tan’s website. It is intended to give employees talking points to use outside the salon to argue that tanning is a good source of vitamin D, and thus a bulwark against all manner of illness including breast cancer, heart disease, and autism.

The industry has also gone on the offensive with tactics that appear cribbed from Big Tobacco’s playbook to undermine scientific research and fund advocacy groups serving the industry’s interests.

Central to the industry’s message is the idea that tanning’s critics—such as dermatologists, sunscreen manufacturers, and even charities—are part of a profit-driven conspiracy. These critics are described as a “Sun Scare industry” that aims to frighten the public into avoiding all exposure to ultraviolet light. The tanning industry blames this group for causing what it calls a deadly epidemic of vitamin D deficiency, and tries to position itself as a more trustworthy source of information on tanning’s health effects.

What tanning’s proponents rarely point out is that the extent of the vitamin D epidemic is disputed, and that even if you need more of the vitamin, you can safely and easily get it from dietary supplements and certain foods.

Even as they themselves use techniques cigarette companies pioneered, some in the tanning industry compare the Sun Scare group to the tobacco industry. “Sun Scare people is just like Big Tobacco, that they’re lying for money and killing people,” Joseph Levy, executive director of Smart Tan, said in the D-Angel video.

Feeling the Heat

The indoor tanning industry’s image has taken a beating since 2009, when the International Agency for Research on Cancer designated UV-emitting tanning devices as carcinogenic. The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Dermatology urge minors not to use sunbeds.

California and Vermont prohibit youths under 18 from tanning indoors, and New York this month imposed a ban for those under 17. Thirty-three states regulate teen tanning to a lesser extent, according to the research firm IBISWorld.

The Federal Trade Commission and Texas Attorney General have tried to rein in marketing messages that misrepresent tanning’s risks. The Texas lawsuit is pending, but the FTC reached a settlement with the industry’s largest trade group, the Indoor Tanning Association, in 2010.

Still, misleading messages continue to be the norm, Democrats on the House Energy and Commerce Committee reported in February. Undercover investigators phoned 300 salons and found 90 percent of the employees they spoke with said tanning did not pose a health risk. What’s more, 51 percent denied sunbeds increase cancer risk. Industry groups say the questions were posed in a leading way and that investigators would have been more fully informed of risks had they visited salons in person.

Despite the bad press, the indoor tanning industry is holding steady. It showed slow but continued growth over the last three years, and revenues are expected to edge up to $5 billion by 2017, according to IBISWorld. White women ages 18-21 are the leading customers: 32 percent of them tanned indoors in 2010, including 44 percent in the Midwest, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An estimated 28 million Americans tan indoors each year.

The Changing Demographics of Melanoma

At an age when most feel invincible, 25-year-old Chelsea Price of Roanoke, Virginia, lives life in three-month increments. In January 2011, she was diagnosed with Stage III malignant melanoma.

Price’s first reaction was giggles. Her doctor, a kidder, had seemed unconcerned about the mole he’d removed, even reassuring her that he did it just to be safe. “I wish I was joking,” he said when he delivered the news.

After two invasive surgeries, Price shows no sign of melanoma today. But Stage III melanoma has a high rate of recurrence, so Price has a skin exam, CT scan, and blood tests every three months to make sure she’s still cancer-free. “It dictates my life,” she said.

Like many melanoma patients, Price is young, female, and a former indoor tanner, though it’s impossible to say with certainty whether the time she spent in sunbeds caused her illness. Price tanned indoors for just a couple of months each year, and she never sunburned. “I am the person who did it safely and in moderation, but yet I’m here,” Price said.

Price is hardly alone. Skin cancer is one of the most common cancers in the United States, and diagnoses of melanoma, though still rare, have increased steeply over the last 40 years. Melanoma among white women ages 15-39 has shown a particularly striking rise, up 50 percent from 1980 to 2004, according to the National Cancer Institute.

The typical melanoma patient has changed in a generation, says Dr. Bruce Brod, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania. Twenty years ago, Brod’s melanoma patients were mainly middle-aged men. Today, he treats mostly young women for the cancer. “I think that’s thanks to the tanning salons,” Brod said.

Misleading Messages

To neutralize its critics, the Indoor Tanning Association mounted an ad campaign in 2008 that claimed there were no compelling links between tanning and melanoma. It also praised UV light as a good source of disease-fighting vitamin D. The campaign’s architect was Richard Berman, the public relations executive whose work to defend the alcohol industry, and discredit unions and Mothers Against Drunk Driving, earned him the nickname “Dr. Evil” among his critics.

FairWarning Editor’s Note: Segments of the video that originally appeared with this story have been taken down. We are working to restore them.

The FTC accused the tanning association of making false claims. The result was a 2010 settlement barring the group from making misleading statements or unfounded health claims. Advertisements suggesting that tanning improves health by providing vitamin D also sparked the Texas case against Darque Tan, a chain with more than 100 salons.

Yet the threat of sanctions has had a limited impact. Some even say the FTC agreement gave the Indoor Tanning Association carte blanche to make any vitamin D health claims it wants, as long as it displays a disclaimer. “The FTC suit was a triumph,” Robbie Segler, president of Darque Tan, wrote on the online industry forum TanToday in 2011.

The focus on vitamin D shifts the debate from tanning’s risks to its potential health benefits in a manner reminiscent of early tobacco marketing, said David Jones, a dermatologist in Newton, Massachusetts. He coauthored a 2010 paper comparing tobacco and tanning advertising that found that cigarette makers once portrayed their products as healthy. “The tanning industry is doing the same thing,” he said.

Vitamin D plays a widely acknowledged role in bone health and immune function, and according to the National Cancer Institute, there is evidence that it could reduce the risk of colorectal cancer. Whether it can prevent other cancers, though, is not yet known.

Sowing Doubt

Taking another page from the tobacco playbook, the tanning industry attacks research linking sunbeds to cancer. Industry leaders insist the relationship between melanoma and UV exposure is not well understood. But DeAnn Lazovich, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota, says the latest research “provides even stronger evidence” that UV light from sunbeds is carcinogenic.

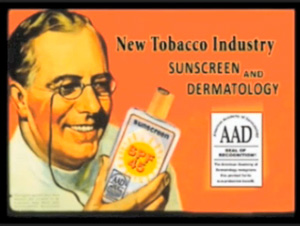

Altered tobacco ad used in an salon employee training video to suggest that doctors once shilled for the tobacco industry and now shill for sunscreen companies. FairWarningThe industry also takes aim at its critics’ integrity. The D-Angel video, using vintage cigarette ads that featured doctors, tries to portray the medical profession in general as having shilled for the tobacco industry. While the American Medical Association pocketed industry money, and some tobacco companies claimed that doctors endorsed their brands, Levy makes the dubious assertion that the medical profession broadly endorsed smoking as healthful. He contends that physicians continue to endanger public health in the interest of profit. “It’s no longer tobacco that they’re selling,” Levy says in the video. “Today, it’s chemical sunscreen and [an] anti-UV message designed to tell you that any sun exposure is bad for you. It’s the same thing as doctors being arm-in-arm with Big Tobacco.”

Altered tobacco ad used in an salon employee training video to suggest that doctors once shilled for the tobacco industry and now shill for sunscreen companies. FairWarningThe industry also takes aim at its critics’ integrity. The D-Angel video, using vintage cigarette ads that featured doctors, tries to portray the medical profession in general as having shilled for the tobacco industry. While the American Medical Association pocketed industry money, and some tobacco companies claimed that doctors endorsed their brands, Levy makes the dubious assertion that the medical profession broadly endorsed smoking as healthful. He contends that physicians continue to endanger public health in the interest of profit. “It’s no longer tobacco that they’re selling,” Levy says in the video. “Today, it’s chemical sunscreen and [an] anti-UV message designed to tell you that any sun exposure is bad for you. It’s the same thing as doctors being arm-in-arm with Big Tobacco.”

Levy is a pivotal figure in defending the tanning industry. While a vice president of Smart Tan, he also served as an officer of a nonprofit vitamin D advocacy group called the Vitamin D Foundation and was the executive director of a the Vitamin D Society, a Canadian group.

Yet the close ties between the tanning industry and the web of nonprofit groups that promote the health benefits of Vitamin D often are not readily apparent. The website for the Vitamin D Foundation, for example, discloses no industry affiliation, though tax documents reveal that its top personnel were all people in the business. In addition to Levy, they include the CEO of Beach Bum Tanning, a chain with 53 salons, and the president of the Joint Canadian Tanning Association, who also owns a large chain of salons.

These groups funnel money to vitamin D researchers and organizations that reinforce the industry’s claims about the vitamin’s health benefits. One such organization is the Breast Cancer Natural Prevention Foundation, which promotes vitamin D for breast cancer prevention. The founders include Dr. Sandra K. Russell, an obstetrician-gynecologist who appeared in advertising for Smart Tan wearing her white lab coat.

Dr. Sandra Russell, a Michigan doctor, has appeared in pro-tanning publicity materials. She recently helped start a nonprofit group that promotes vitamin D and sunlight for cancer prevention. FairWarningSuperman vs. Clark Kent

Dr. Sandra Russell, a Michigan doctor, has appeared in pro-tanning publicity materials. She recently helped start a nonprofit group that promotes vitamin D and sunlight for cancer prevention. FairWarningSuperman vs. Clark Kent

In promoting the health benefits of UV-induced vitamin D, the tanning industry must tread carefully—after all, health claims were central to the FTC complaint, the Texas Attorney General’s case and the congressional report that blasted the industry. But the FTC cannot police what salon employees say when they are off the clock, and the D-Angel training program takes advantage of that.

In the training video, Levy is explicit about what employees can say at work and what they should say only on their own time. He encourages the D-Angels to follow what he calls the “Clark Kent/Superman” model. At the salon, employees should be Clark Kents who refrain from making health claims about vitamin D. Beyond salon walls, however, he urges employees to be superheroes who expose the lies about tanning and vitamin D. “Outside the salon, you can be a D-Angel,” Levy says. “You can promote a message to your friends and neighbors that Sun Scare is just like Big Tobacco. They’re lying for money and killing people.”

But the reality for salon employees is more complex, says Lisa Graubard, a 15-year industry veteran who managed three salons on the New Jersey shore. Graubard, who lives in Lakewood, New Jersey, is not anti-tanning but says salon employees need better training. “There are definitely salons in the industry that are like, ‘We’re not going to use the c-word,'” she said, referring to the cancer risk.

Graubard acknowledged that some of her own customers kept tanning even after developing skin cancer. One man, she recalled, came to tan still bandaged from melanoma surgery. Graubard left the business after years of tanning left her face discolored.

The clientele at Graubard’s salon grew increasingly younger; eventually girls as young as 14 were begging to tan without the legally required permission slips. She’d say no, but a chain salon down the street was known to turn a blind eye to the rules. “Consent? It was like a joke,” she said.

Meghan Rothschild, a self-described “splotchy white girl” from Northampton, Massachusetts, says tanning gave her a confidence boost that she still misses today, eight years after being diagnosed with melanoma at age 20. She was angry with herself when she got the news. “The only thing I could think of is, ‘You did this to yourself, you idiot,'” she said.

Today, Rothschild blames an industry she says downplays tanning’s risks, along with inadequate regulations that leave the decision of whether to tan up to youth who don’t always understand the consequences.

Schools teach kids to avoid alcohol and tobacco, Rothschild said. “But the kids aren’t smoking anymore. They are using tanning beds. The tanning booth is going to be the cigarette of our generation.”

FairWarning (www.fairwarning.org) is a nonprofit, online investigative news organization focused on safety and health issues.