In 1979 another in a growing line of alien species hitched a ride on a fishing skiff from a remote village on Mexico’s Baja California peninsula to land on Rasa Island, a tiny sun-blasted wafer of rock in the Gulf of California. The invader was Enriqueta Velarde, a petite 25-year-old Mexican graduate biology student who looked 18, with a comely smile and an adventuring heart. It was the launch of her Ph.D. research into one of the island’s resident species, the Heermann’s gull, a petite, pretty bird about which almost nothing was known. In fact, little was known of the island beyond its desolate oddities: thousands of mysterious stone cairns and pathways thought to have been made by guano miners in the 19th century, three wooden crosses marking unremembered graves, a stone hut crumbling with the region’s frequent temblors.

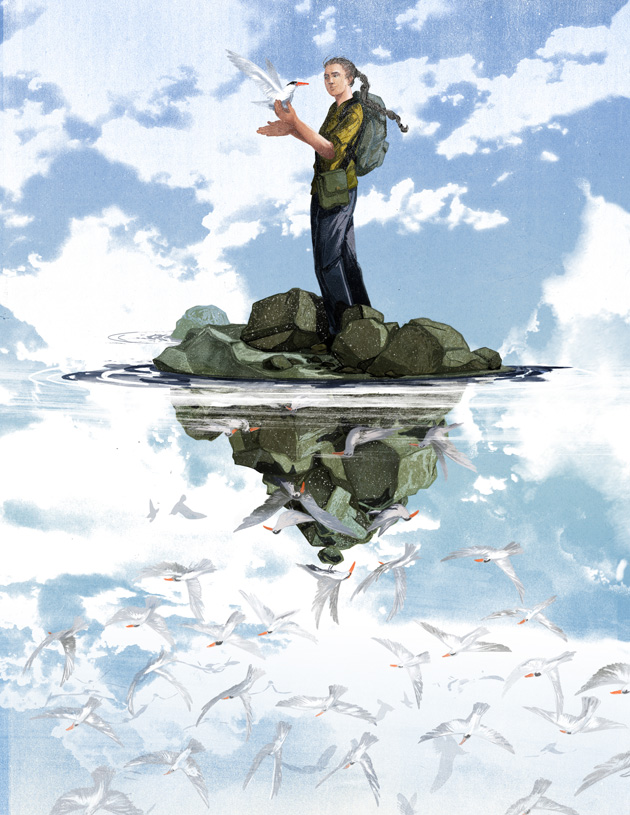

Velarde arrived at the beginning of the three-month cacophony known as the breeding season, when Rasa’s 148 desert acres become a fecund madhouse of hundreds of thousands of noisy, copulating seabirds who have for at least millennia chosen this smidgen of refuge because it’s flat in a world of mountains and because it was once free of terrestrial predators that threatened their eggs and chicks. The birds arrive from coasts to the north and south, homing so faithfully to Rasa each year that at some time in the distant past they diverged from their progenitors to become their own kind: species we now call elegant terns and Heermann’s gulls, virtually all of whom nest only here.

The island had been of interest to ornithologists as early as the 19th century, but though some intrepid adventurers had visited, none had stayed. Velarde’s landmark arrival would prove a rarity in both the human story and the biological story: a successful invasion by one who would not go on to populate the island with her own kind, yet whose presence would transform Rasa and its larger ecosystem forever.

As an undergrad biology major, I joined Velarde for her second field season on Rasa in 1980. Last year, I returned. Some things haven’t changed. Velarde still moves across the island in the slow-motion style I remember, treading between one gull nest and another, foot poised in the air as she examines where to plant it to avoid stepping on eggs and chicks that perfectly mimic the ground splattered with guano in all its wet and dry incarnations. But Heermann’s gulls nest on virtually every square inch of Rasa, and even our careful footfalls violate the territorial integrity of one bird after another so that we trigger a cascade of incensed nesters who burst into the air and scream past our heads, firing globby rains of shit upon us. A few slap us with webbed feet or smack us with bills. Velarde gently redirects them with a clipboard cocked over her head.

We’re headed to the tern colony in one of the largest of the island’s 11 small valleys. This is where I spent most of my time in 1980, perched on uncomfortable rocks, baking in the sun, observing through binoculars the nearly incomprehensible machinations of delicate white birds—the rare elegant terns nesting alongside nearly identical, but more common, royal terns—all jammed only a bill’s length from their constantly jabbing neighbors. Compared with the dull roar of a gull colony, the tern colony sounds like a jet-fueled apocalypse slipping off a million broken flywheels, so shrill and piercing it’s a physical assault. Long before we can see these birds, we can hear them.

The tern colony at Rasa Island in 2011. : Julia WhittyBut when we try to climb the old path to the tern valley we routinely walked in 1980, we’re stopped by thousands of terns nesting on the ridge, a rocky place they never utilized back then. We choose not to trespass through their colony, since nesting terns are hypersensitive to disturbance, and in fleeing us they could lose their eggs to marauding gulls. So we backtrack and try to cross in a different place, only to be stymied by more nesting terns. When we finally find a route, we come face-to-face with a sight I could never have imagined in 1980: Where once there was a small amoeba of a colony of terns, today there are multiple gargantuan superorganisms of colonies usurping nearly the entire valley.

The tern colony at Rasa Island in 2011. : Julia WhittyBut when we try to climb the old path to the tern valley we routinely walked in 1980, we’re stopped by thousands of terns nesting on the ridge, a rocky place they never utilized back then. We choose not to trespass through their colony, since nesting terns are hypersensitive to disturbance, and in fleeing us they could lose their eggs to marauding gulls. So we backtrack and try to cross in a different place, only to be stymied by more nesting terns. When we finally find a route, we come face-to-face with a sight I could never have imagined in 1980: Where once there was a small amoeba of a colony of terns, today there are multiple gargantuan superorganisms of colonies usurping nearly the entire valley.

“Does it look like a lot more terns than you remember?” Velarde shouts above the mayhem.

She estimates there are some 200,000 now. Seven times the 1980 number.

A multitude of factors have allowed these birds to buck the trend of dismally declining wildlife. Each traces its genesis to this small, now gray-haired woman before me.

It took me years to see that Enriqueta Velarde was part of a widely and thinly dispersed bunch of like-minded misfits, frequently women, who travel to earth’s last hinterlands and guard their wilderness nests with near-mythical ferocity. I met the matriarch of this clan, Jane Goodall, on the 25th anniversary of her work with wild chimpanzees at Gombe Stream in 1985. She didn’t actually expect our small film crew to persevere all the way to Gombe, I could tell, to weather the challenges she routinely encountered en route to the chimps’ world. And suffer we did: Arrested in Dar es Salaam, shipwrecked on Lake Tanganyika, rescued by Zairean (now Congolese) war refugees, we hungered and thirsted and lived for a while on bottles of konyagi and nothing else. When we finally made it to Gombe, long after our scheduled arrival, beaten down by our cinematic adventures, Goodall greeted our knock at her door in the wilderness in utter darkness with serene and unruffled composure and listened bemusedly as we breathlessly unloaded our stories. She’d already heard, or lived, some version of all our escapades.

From Goodall I learned the power of one. Alone, she had managed to preserve Gombe’s postage stamp of verdancy amid a combat zone of stripped forests and eroding hillsides unable to support either people or chimpanzees. In ecology-speak, a keystone species is one with a disproportionate effect on its environment relative to its biomass. In Goodall, I realized, I’d met a keystone individual.

Over time I met other keystone humans stubbornly attached to remote rainforests, wetlands, mountains, deserts, and coral reefs, influencing these areas far beyond their mortal size. A few had attracted enough National Geographic coverage to become household names, though most accepted obscurity as a prerequisite of isolation. Yet their unknown stories of quest, conflict, discovery, and understanding are important to us—resuscitative sagas in a demoralizing age.

And that’s a kind of keystone idea that science itself is grappling with in the face of obstinately gloomy news about the natural world. The authors of a clarion paper in Trends in Ecology and Evolution last year defined the challenge: “Relentless communication of an impending mass extinction is, self-evidently, having insufficient impact on politicians, policy makers and the public, and could eventually even be counterproductive for improved conservation,” wrote Stephen Garnett and David Lindenmayer. “Researchers need to provide the science not only for the campaigns lamenting environmental loss, but also, most importantly, for those celebrating the effectiveness of conservation.”

That effectiveness is consistently underrated. It has been only 164 years—an eyeblink in the human life span—since George Perkins Marsh, a congressman from Vermont, bore witness to the loss of Eastern forests and suggested we ought to conserve them. (His writings helped launch the modern conservation movement as well as the Adirondack Park, today the largest publicly protected landscape in the contiguous United States.) Marsh’s heretical notion came on the heels of near-total deforestation in the East and only months before unbridled gold fever would level California’s wildlands. Yet since then we have with radical speed rearranged our relationship to 160,365 landscapes to preserve 14 percent of terrestrial earth and created 6,967 marine protected areas sheltering 1 percent of the planet’s ocean. We’ve enacted sweeping legislation to conserve flora and fauna in most nations and even across tricky international borders. We’ve widely abandoned the notion of infinite resources and begun to redirect our human story toward the idea of sustainability.

While the dominant meme sees only our destruction of nature, a keystone idea might be that we’re actually in the middle of a new process whereby nature is tweaking the design specs on its most ingenious piece yet of evolutionary engineering: human understanding.

Enriqueta Velarde rarely stops, and when she does it’s only because it’s too dark to do anything more. She falls into a sleeping bag nestled inside another sleeping bag enclosed in a decades-old woven Yucatán hammock that once belonged to her great-aunt, which folds around her like a chrysalis. She snores enormously in the night, a familiar lullaby to 33 generations of gulls hatched and raised in the colony behind the hut. At first light she awakens and fights free of her cocoon.

Enriqueta Velarde.: Julia Whitty

Enriqueta Velarde.: Julia Whitty

“What’s that noise?” I ask.

She’s standing in front of the window in our room brushing her waist-length hair.

“It’s the great blue heron.”

I roll out of my hammock and grab my binoculars. This is one of countless mysteries from 1980 that Velarde has since solved. It takes me a while to see what she knows: up on the hill, a perfectly camouflaged 5-foot-3-inch-tall bird of the quiet seashore or lakeside, stalking as if on stilts and stabbing its six-inch-long bayonet at any gull foolish enough not to abandon hope and eggs. Gulls by the score are mobbing the heron, screaming on dive-bombing guano-firing runs. But the heron is an eating machine, stalking and stabbing, robbing eggs and chicks from one gull pair after another, swallowing their entire season’s reproductive effort down its snaky neck.

In 1980 we’d puzzled over the morning clouds of mobbers but were never able to identify the intruder they were fighting. Mostly we were on guard for human interlopers, since one of our primary purposes then was to protect Rasa from the incursions of unregulated sightseeing ecotourists and from fishermen who raided the tern colonies and sold the eggs as aphrodisiacs. Both economies decimated the birds’ population, driving it from an estimated high of 1 million in 1940 to maybe 5,000 in 1973.

In 1980 we intercepted two raiding parties, one friendly, the other not so, though both backed down before they got any eggs. And that was pretty much the last of them. News got around that Rasa was defended by a small, smiling but unyielding woman. Plus, Velarde befriended many would-be poachers and charmed them with her ready supply of jokes and impressed them with her annual migration, as predictable as a bird, to live on a waterless bedlam, often alone, seemingly happy. The fishermen respected her eccentricity. They also succumbed to the seductiveness of her story. That these waters—home to rare sea turtles, fish, porpoises, and whales—were among earth’s most biologically productive. And that these islands—home to unique birds, bats, lizards, and snakes—were as irreplaceable as the Galápagos Islands and a genuine Mexican treasure.

“Over time the people in the fishing villages forgot about eating seabird eggs,” Velarde says. “And have you noticed how the terns, though skittish, aren’t as skittish as before?”

Given protection, Rasa’s excitable wild birds grew tamer. Yet their numbers did not rebound. Not 5 years after the egg raiders all but disappeared, and not 10. Were the 30,000 elegant terns of 1980 all there would ever be on earth? The problem, Velarde suspected, was the island’s other intruders: the hitchhikers who’d arrived with 19th-century guano miners—alien rats and mice that grew fruitful and multiplied on Rasa’s three-month bonanza of seabird eggs and chicks. At night, Velarde says, she would hear the frantic alarm calls of the parent birds, helpless as their chicks were being gnawed to death.

So between 1993 and 1995, Velarde paired up with Jesús Ramírez, a Oaxacan from the Ecology Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, to conduct a rodent eradication. They followed a New Zealand model that involved setting out hundreds of anticoagulant bait stations in every valley, hillside, and beach on the island. For two months they checked and rebaited each station every day, working throughout the winter, when the seabirds were away and the starving rodents were suffering their annual population crashes. But before the monitoring could be completed, Ramírez was killed in a car wreck in Mexico City.

“He spoke often of tequio,” says Velarde, “the Aztec word the people of Oaxaca use when they talk about communal effort, the practice of able-bodied adults coming together to build a house or a school. When the time came to do the follow-up monitoring on Rasa, many people came forward in his memory—his girlfriend, siblings, friends, and colleagues—his tequio, assembled to complete his work.” Their efforts confirmed that Rasa was free of rats and mice, a rare successful double eradication that holds to this day.

Velarde weighs gulls’ eggs on the beach near her hut. : Julia WhittyIn the late afternoon Velarde leads the way across the island, stopping every few steps to scan with binoculars. We spy a few pieces of PVC pipe slowly disappearing under drifts of powdered guano. These are the last remnants of the bait stations deployed by Ramírez. “I never could bring myself to remove them,” she says.

Velarde weighs gulls’ eggs on the beach near her hut. : Julia WhittyIn the late afternoon Velarde leads the way across the island, stopping every few steps to scan with binoculars. We spy a few pieces of PVC pipe slowly disappearing under drifts of powdered guano. These are the last remnants of the bait stations deployed by Ramírez. “I never could bring myself to remove them,” she says.

She’s headed across a rocky hillside crisscrossed with the trails built by men who once mined up to 10,000 tons of guano a year from this island. Heermann’s gulls nest in the remains of their tracks. It’s been a couple of weeks since they laid their eggs, and the embryos are stirring, driving the gulls to ever more aggressive attempts to repel us. They scream so insanely in our ears and shit so voluminously upon us that I cringe. I remember melting down at this point in the 1980 breeding season, standing alone in a gull colony and screaming at the birds to shut the fuck up. Velarde is unflappable. She points with her clipboard at objects of interest: a nest with a dried seahorse in it; a nest with two eggs and a bleached chick skull in place of the third egg, a slightly Hieronymus Bosch incubation triptych.

Since the rodent eradication, the number of elegant terns has skyrocketed. The 240,000 Heermann’s gulls have remained steady, though they’ve radically rearranged their nesting success. Velarde knows this because she’s marked and counted seemingly countless eggs and nests and has banded around 36,000 chicks over the years, creating one of the most comprehensive seabird databases on earth.

Now she’s leading the way to parts of Rasa she’s monitoring in hopes that the rodent eradication may have enticed back seabirds long gone from the island—rare murrelets and shearwaters, secretive birds of the open sea who come ashore only under cover of night to nest in burrows. During the day, the adults leave their chicks alone underground, where they are utterly defenseless against rodents. At some point during the rat-beleaguered 20th century, these birds abandoned Rasa. Velarde hopes they may now find their way home again. That, she says, would be the ultimate memorial to Jesús Ramírez.

Eradication is a paradoxical conservation tool. The antithesis of life—poisons, traps—is used to revive life. It’s like chemotherapy for the wild. All of these campaigns trace back to the late 1950s, to a handful of keystone progenitors in New Zealand concerned about the fate of white-faced storm petrels, diminutive seabirds who also come ashore only at night. Hobbled by legs designed to dance on water, not walk, these birds shamble down their burrows on the crutches of their wings, leaving them easy prey for alien rats. In 1959, funded with a whopping £5 from New Zealand’s Wildlife Service, members of the Forest and Bird Protection Society scattered a common household rodenticide around the petrels’ burrows on two tiny islands. It worked.

Since Velarde’s and Ramírez’s pioneering work on Rasa, alien predators and herbivores have been eradicated from 29 other Mexican islands at an astonishingly low cost of about $23 an acre. The once-bleak prospects of 88 endemic populations of tropic birds, lizards, land birds, trees, succulents, and wildflowers have been revived. More than 200 Mexican seabird breeding colonies have been liberated from destructive menageries of rats, mice, cats, goats, dogs, donkeys, sheep, rabbits, and pigs. Many reinvigorated Mexican species—including elegant terns and Heermann’s gulls—now swell the ranks of US wildlife during their nonbreeding seasons.

But Velarde’s work wasn’t finished. Boosted by US donors and with the help of a few American researchers, she recruited a team of dozens of Mexican scientists to travel the Gulf of California on Mexican navy boats and undertake the first census of its more than 240 islands, a Darwinesque endeavor impelled by a modern urgency. The collaborative research confirmed the region’s unique yet precarious biodiversity and led in part to Mexico receiving $25 million from the Global Environment Fund in 1992, followed by the creation of Mexico’s first marine reserve, in the northern Gulf of California, and culminating in UNESCO declaring the islands of the Gulf a biosphere reserve in 1995 to preserve and restore natural ecosystems and develop sustainable alternatives to egg-gathering for local people.

The original keystone idea that the Gulf of California was a Mexican treasure of unique biodiversity began to trickle out to people living in the Gulf’s remote fishing outposts. Velarde initiated an education exchange with the indigenous Comcÿac people, learning from them about these islands and waters, their traditional home, and training their students as citizen scientists. She invited students from a local fishing village to visit Rasa and join her fieldwork. She participated in an innovative program that hired a famous cartoonist to create a series of graphic novels where beautiful women, bad guys, and handsome heroes sparred over the dangers of introducing alien species to the islands. The comic books became wildly popular, says Velarde, the fishermen eagerly awaiting the next installment.

By 11 o’clock on Rasa, the temperature in the sun, a.k.a. the entire island, is well over 100 degrees. Velarde is working fast in a gull colony full of birds sitting on eggs and gaping with bills wide open to relieve their heat stress. She holds in her lap a bird wearing a handmade straitjacket and a hangman’s hood, each scrap of cotton used and reused so many times over the years that they’re stained a guano camouflage. The bondage kit subdues the bird, allowing Velarde to weigh it, take its wing and bill measurements, and extract a blood and feather sample, the whole alien abduction process lasting five minutes before the animal is set free to return to its eggs. Some of these banded birds are 25 years old and have been data-mined so often by Velarde over the years that they’re now virtually impossible to catch.

But not for José Arce Smith, who goes by the nickname Guero, a fisherman from the village of Bahía de los Angeles, three hours away by boat. He’s an enormous jolly man who can catch fish with lures torn from a T-shirt and clean his haul so thoroughly that not even a gull can make a meal of the remains. Tiptoeing among Rasa’s gulls in his oversize Converse sneakers and bright yellow shorts, he sets the trap for Velarde’s wiliest birds with a tiny lasso, steps back a few paces, and yanks the string. A hundred squawking gulls erupt off their nests as the banded bird is beamed unhurt into his arms.

Arce Smith and Velarde with a captured gull: Julia Whitty

Arce Smith and Velarde with a captured gull: Julia Whitty

Arce Smith also makes a living escorting ecotourists and sportfishers through the Gulf. But this year’s stalled economy combined with Mexico’s violent drug woes are keeping Americans away, he says, making his work with scientists all the more vital. This season for the second time he’s brought along his nephew, Rosendo Alexis Olachea. There’s nothing for teenagers to do after school, says Arce Smith, and there are drugs in the village these days.

Velarde and Rosendo measure a gull’s wing: Julia WhittyHe could hardly find a more eager helper. Rosendo is so intensely interested in science that he spends his off-hours studying a copy of The Sibley Guide to Birds. We get a sense of how deeply the keystone idea has shaped his thinking when the Mexican sailors who deliver our food and water drop our supplies and then disappear. After a while we get a call from their captain, offshore and out of sight on the big ship. Where are his marinos? he wants to know. Glancing at the lagoon, we see them industriously prying oysters from the rocks. Rosendo volunteers to run down and inform them that their captain is growling—though he also takes the opportunity to tell them off about eating oysters: This is a protected area and a marine reserve. His eyes blaze. The sailors leave their limes on the rocks and sheepishly retreat.

Velarde and Rosendo measure a gull’s wing: Julia WhittyHe could hardly find a more eager helper. Rosendo is so intensely interested in science that he spends his off-hours studying a copy of The Sibley Guide to Birds. We get a sense of how deeply the keystone idea has shaped his thinking when the Mexican sailors who deliver our food and water drop our supplies and then disappear. After a while we get a call from their captain, offshore and out of sight on the big ship. Where are his marinos? he wants to know. Glancing at the lagoon, we see them industriously prying oysters from the rocks. Rosendo volunteers to run down and inform them that their captain is growling—though he also takes the opportunity to tell them off about eating oysters: This is a protected area and a marine reserve. His eyes blaze. The sailors leave their limes on the rocks and sheepishly retreat.

As the breeding season progresses, the birds on Rasa work even harder. All day and night they bathe in the lagoon, fly offshore to fish, trade incubation duties with their partners, feed insatiable chicks, rearrange threadbare nests, perform courtship rituals, and squabble with neighbors. Yet it’s not all drudgery. Their accelerating labors are done with a palpable sense of excitement. It’s like a manic party of oversexed revelers crowding onto a flat, hot, inhospitable, and temporary desert home. It reminds me of Burning Man.

Like Burning Man, Rasa’s crowds are outgrowing their festival grounds. Velarde’s curious about a small colony of Heermann’s gulls on Cardonosa Island, 4 miles north of Rasa. How related are they to Rasa’s gulls? If Rasa’s birds have rebounded to the point that the island is full and some are shopping for real estate, satellite colonies will become important developing reservoirs of genetic biodiversity.

The blood and feather samples she’s collecting are part of a collaboration with Enrico Ruiz, a young postdoc at the University of California-Merced. Ruiz, a Mexico City kid, was smitten with the wilderness when he visited the Gulf of California to study fish-eating bats. He’s returned now, decked out in brand new adventurer’s gear, to test the relatedness of the Cardonosa gulls to the Rasa gulls. He’s also trying to answer a key question related to Velarde’s earlier observations: If most Heermann’s gulls on Rasa are monogamous and return to the same valley or ridgeline where they were born, many to the same nest site, how is inbreeding avoided?

“There’s a lot to be said,” says Velarde, “for mating with your close relatives from the same valley or hillside. If you come from strong stock, then you’re mating with strong stock.” Still, it’s important to avoid a genetic bottleneck. For this, the birds likely employ the swingers’ solution of swapping DNA via cuckoldry. Genetic analyses increasingly reveal that few monogamous bird species actually are—at least sexually speaking. These findings tend to splash across human headlines as the “secretly depraved life of birds.” But from an evolutionary point of view, there may be no better strategy than to bond with a relative and then dally with an attractive stranger with novel genes. From a conservation point of view, says Ruiz, it’s good to know where the most robust genetic reservoirs lie, perhaps in only one or two valleys or hillsides on the island.

Regardless of what’s being done or where, it’s a gigantic breeding year on Rasa. After two seasons of total failure—Velarde discovered this to be typical in El Niño years, when keystone Gulf species, sardines and anchovies, migrate away from the island—La Niña of 2011 is delivering mega ocean productivity. There are so many fish offshore that many of Rasa’s more experienced gull couples are producing four-egg clutches, a rarity. Still, Velarde is worried. Among the regurgitations bestowed upon her by captured gulls (and eagerly dissected during her breaks), she finds only mackerel, anchovies, and lanternfish—big-eyed dwellers of the deep that rise to the surface at night—but not a single sardine.

She’s concerned because the Gulf of California sardine fishery, Mexico’s largest by volume, landed more than a quarter million metric tons the year before. She knows the Gulf is a wasp-waist ecosystem: ecology-speak for a delicate food web dependent on forage fish (sardines and anchovies) that are virtually the only predators of all below them (plankton) and virtually the only prey of the tiers above them (bigger fish, seabirds, marine mammals). They’re notoriously unstable systems. Mismanaging them, we’ve created our most epic fishery fails to date. Mexico just received a sustainability certification for its sardine fishery from the Marine Stewardship Council, which would vastly increase market demand in the US. Velarde fears that the fish, keystone to all Gulf species—including humans—will crash.

But for now the island’s so full of birds that some gulls are nesting on the small beach by the lagoon. It seems a cooler and more refreshing locale—until the flood tides of the full moon arrive. One afternoon the water licks up and lifts the eggs off their nests and rolls them along the bottom. The parents swim back and forth, trying to squat through the water and incubate. When the tide recedes they sit briefly on one egg before walking away to anxiously sit on another. But night brings an even higher tide, and by morning the beach is strewn with eggs too scattered to be recovered. The gulls give up.

“Next year, they won’t nest there,” says Velarde. “They don’t repeat their mistakes or those they’ve seen others make.”

It occurs to me that Velarde’s knowledge of this place—the birds, the waters, the climate cycles, the human impacts—is so deep that it may well surpass even that of our hunter-gatherer forebears. And this is true for all of us, however buffered we are from the outdoors. That’s because Velarde and Goodall and their investigative kin are pioneering a connection with our world based on systematic observation, repeatable tests, and modifiable deductions, a scientific tool set that allows us not only to create a truly intimate relationship with nature, but also to bestow it on anyone who cares to learn it. Most importantly, it gives us something no ancestor from our low-tech past ever had: the key to radical self-correction—on a local or global scale—of our, or others’, mistakes.

At the end of his stay on Rasa, Enrico Ruiz carries with him one of Enriqueta Velarde’s most prized possessions: a fragment of eggshell her trained eye tells her belongs to a bird other than a tern or gull. Back in the lab in California, he extracts enough DNA to verify her hunch—that its owner is an extremely rare seabird, endemic to the Gulf of California, known as the Craveri’s murrelet. These tiny penguinlike birds, smaller than robins, were first described nesting on Rasa in 1865 but had not been seen since midway through the rodent-infested 20th century. Now, thanks to their human tequio and their own stubborn resilience, they’ve found their way home again.