St. John's wort plant<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/macrodomo/6271617359/sizes/z/in/photostream/" target="_blank">Macrodomo</a>/Flickr

St. John’s wort is a small, yellow-flowered herb whose name derives from one of its first known uses—warding off evil on St. John’s Day, June 24. Now, Americans shell out roughly $55 million a year for SJW at big-time distributors like Whole Foods, GNC, and The Vitamin Shoppe, making it one of the most popular herbal remedies on the market. Usually taken in the form of capsules or tea, the supplement has demonstrated benefits in treating mild to moderate depression. Rather surprising, then, that it’s also been shown to negatively interact with some of the most commonly prescribed pharmaceutical antidepressants on the market.

Safe to say that’s fairly counterintuitive, and that it could even be dangerous. What’s more, SJW has also been shown to reduce the efficacy of some oral contraceptives. It’s even suspected to have caused unplanned pregnancies. (One woman reported having been prescribed birth control for more than nine years and experiencing an unintended pregnancy just six months after starting her SJW treatment.)

But lots of drugs have potentially dangerous interactions. The real problem here lies in transparency to consumers—a problem that goes directly back to the supplement’s manufacturers. In a 2008 study published in BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine that tested 74 different SJW brands, less than a quarter of the product labels identified possible interactions with antidepressants. Even more disturbing was that only 8 percent identified possible interactions with birth control.

Many groups, like the Center for Science in the Public Interest, have tried to push the FDA to standardize SJW labels to properly reflect possible dangers. But since supplement makers are not required by law to warn consumers about health risks associated with their products, it hasn’t been easy. “These companies fight warning labels like the dickens, and whether they intend it or not, that affirms the belief that natural products are unequivocally good for you,” says Stephen Gardner, litigation director at CSPI.

So why don’t federal regulators force the supplement industry to include warning labels on their products? One big reason is that the industry has powerful allies in Washington. The current murky regulatory force in the supplement world is the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which lets supplements fly to the shelves without first having to demonstrate either safety or effectiveness to the FDA. Unlike prescription meds, the burden of proof for supplements resides with the federal government: The FDA has to prove that products are unsafe after the fact, rather than manufacturers having to prove that they are safe for use in the first place. (Think back to weight-loss supplement ephedra, which took the FDA more than seven years to ban—despite being conclusively tied to heart attack, stroke, and death.)

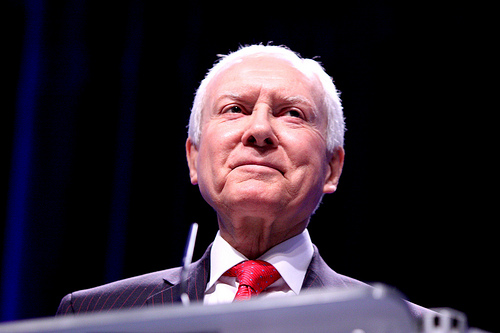

Many have taken issue with the DSHEA, and in February 2010 Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) introduced a bill that would increase regulation of dietary supplements that might pose health risks. Enter Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), who has received upwards of $888,000 in campaign contributions from the health product industry since 2002. Hatch, one of the lead authors of the 1994 DSHEA, has even stronger ties than that—both his son and five former aides are lobbyists in Washington representing the very industry funneling him all that campaign cash. It shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise then that shortly after McCain’s bill proposal, Hatch met with the Arizona senator for some “real talk” on supplement regulation. In a letter released after their private meeting, Hatch thanked McCain for withdrawing his support for parts of the bill that “would do great harm to the dietary supplement industry.” A castrated version of the bill eventually made it through, and the supplement industry came out unscathed.

More efforts have been made at regulation since. Last year, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill) introduced a new bill requiring that supplements that could cause health problems or interact with other drugs—like St. John’s wort—display mandatory warning labels on their products. The bill has not yet been up for a vote, but the industry has already riled up huge opposition—headed, you guessed it, by Hatch himself. The main argument, it seems, is going to hinge on the necessity of labeling products derived from natural sources.

“Supplements are largely based on food and widely considered to be safe, so they don’t need to be labeled,” says Mike Greene, vice president of government affairs at the Council for Responsible Nutrition, the industry’s largest trade group. “For example, you don’t see anyone labeling grapefruit, even though it interacts with Lipitor.”

Whether or not the Durbin bill will make it through the Senate remains to be seen. In the meantime, though, Gardner takes issue with Greene’s argument. “You don’t see people selling grapefruits as cancer cures,” he says. “Look, we’re not interested in stopping people from buying SJW if they know what they’re getting. But we are interested in stopping them if they’re in the dark about it. These companies have prevented people from knowing when they should question them. That’s not logic and that’s not fair.”