SHORTLY AFTER 4:30 P.M. ON MONDAY, April 14, 2003, the power went out at the Motiva refinery in Port Arthur, Texas. The massive plant shut down instantly and, as is common when something goes wrong at a refinery, the “product” in the pipes — tens of thousands of pounds of highly pressurized liquids and gases — was released through the smokestacks. In this particular incident, 256,653 pounds of toxic chemicals were hurled into the air over the next 24 hours.

“That refinery was blowing hot,” says Hilton Kelley, the tall, sturdy, 42-year-old founder of a local group called the Community In-Power Development Association. “And that cloud of poison hung over us until, I’d guess, 10 or 11 that night.”

It wasn’t the first such incident, or “upset,” at the 3,800-acre plant, a century-old, grime-stained industrial giant that glowers above Port Arthur’s pancake-flat landscape. Motiva had experienced seven in just the previous 11 weeks, and the record of Port Arthur’s other refineries wasn’t much better; during one six-month period last year, barely a day went by without a toxic accident of some kind.

And so, Kelley knew just what to do as 128.3 tons of vaporized poisons — including sulfur dioxide, hexane, carbon monoxide, isobutane — began sifting earthward. He went door to door, warning his neighbors to either leave quickly or stay inside with the windows shut tight. He also made a phone call, to a toll-free number at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state agency charged with monitoring airborne toxic releases.

When a TCEQ staffer finally arrived, Kelley says, “I asked the guy, ‘You got any air-monitoring equipment with you?’ And the guy said, ‘No.’ And I thought, So…what? You’re here to watch?”

“Around here,” Kelley says, “it turns out April 14 was just another day.”

PORT ARTHUR AND POLLUTION have gone together ever since Texas’ First major oil well was discovered in 1901, at the Spindletop derrick just up the road in Beaumont. The city’s First refining facility was built that same year, and Port Arthur boomed along with the oil business. Janis Joplin was born here, the daughter of a refinery engineer, and sang in the choir at First Christian Church in the ’50s. But by the 1990s, mechanization had taken away most of the refinery jobs, and Port Arthur — along with much of the Gulf Coast oil belt between Houston and Baton Rouge — fell on hard times.

Today, Port Arthur resembles nothing so much as a gated community in reverse. Sprawling refineries hide behind chain-link fences topped with razor wire and guards at the exits. Outside the fences, in the predominantly African-American neighborhood known as the Westside, streets are potholed, and every third or fourth house is empty and overgrown. All around Port Arthur, clapboard Victorians from a more prosperous era stand in want of paint and shutters, and tall weeds grow in the sidewalks of once-busy downtown avenues. Unemployment hovers around 13 percent, and the only buildings that see much activity appear to be City Hall and the offices of the local paper, the Port Arthur News.

Spend a few days in town and you’ll find that the air always carries a throat-tickling mix of murky sea spray from the Gulf of Mexico and low levels of airborne sulfur, given off by the refineries. At night, above the dark shapes of enormous live oaks, the sky often glows orange with flares and the plants’ thousands of lights; a constant, low electric hum from the refineries blankets the city like east Texas humidity. Port Arthur ranks high in just about every national pollution statistic — the city and surrounding county are among the top 10 percent for major chemical releases; environmental cancer risk; levels of carcinogens; and levels of toxins that interfere with fetal development. According to a study by the Austin-based Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition, more than 20,000 children in the area are exposed to toxins that can cause cancer, learning disabilities, and birth defects.

This, in other words, is the kind of place the federal government promised to start cleaning up a generation ago, when Congress passed a series of sweeping environmental laws including the Clean Air Act of 1970. The act never quite lived up to its name; many companies ignored its mandates, or learned to accept environmental fines as part of the cost of doing business. But in the 1990s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began cracking down on companies that were violating the law, threatening power plants and refineries, including some in Port Arthur, with costly lawsuits if they did not install state-of-the-art filters and scrubbers.

Now, the Bush administration has pulled back on that effort — and, according to critics, demolished the foundation of the Clean Air Act itself. It has issued rules that relax key provisions of the act, allowing thousands of dirty power plants and other industrial sites to increase pollution without any Fines or penalties. Fifteen states have filed suit to block the changes; a national group of state and local air-pollution officials says the rules will result in “unchecked emissions increases that will degrade our air quality and endanger public health.”

Though the administration characterizes the policy shift as minor — a “response to a longstanding, bipartisan call for reform,” as an EPA briefing paper puts it — changing the clean-air rules has long been a top priority for companies that have donated millions to the Bush campaign. In March 2001, just two months after Bush took office, the National Petroleum Refiners Association, which represents several of the companies operating in Port Arthur, told the U.S. Department of Energy in an internal memo that “the EPA’s enforcement campaign against U.S. refineries should be halted and re-examined.” And that, in effect, is what happened: The administration’s proposed changes would legalize what until now were violations of the Clean Air Act, in some cases creating a permanent exemption from rules that were supposed to have kicked in three decades ago. The EPA has also released a plan it calls “Clear Skies,” which would loosen Clean Air Act standards for most of the nation’s power companies. And it has taken the pressure off companies that violate the law, cutting inspections staff and reducing Fines and criminal charges against polluters.

“What is so profound is that this is the First time in the history of the Clean Air Act that we are going in the wrong direction,” says Judith Enck, a policy adviser to New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer, who has Filed suit challenging the administration’s new rules. “For 30-plus years, there had been a gradual tightening of standards. This is the First time the federal government has tried to weaken the act. We’re in uncharted territory here.”

HILTON KELLEY CAME BACK to Port Arthur in February of 2000, a local Eagle Scout turned Hollywood stuntman. “I was working on the TV show Nash Bridges with Don Johnson,” Kelley recalls. “I decided to make a visit home, like I did every few years, and what I found was beyond belief. Because of the increasing air pollution, the people of Port Arthur were too sick to help themselves. They were beat down. The town was dying, and I saw a need here that I thought I could fill.”

Three months later, Kelley put his Hollywood career on hold and headed home. “That last day at work, Don Johnson said, ‘We’ll miss ya, Hilton. Go and get your hometown cleaned up and come back to work,'” remembers Kelley, doing a dead-on impersonation of the star’s gravelly voice. Back in Port Arthur, Kelley hooked up with two local ministers — Reverend Alfred Dominic and Dr. Roy Malveaux — who had, after years of watching their town’s decline, started a campaign to clean up the refineries. “Our goal,” says Reverend Dominic, “has never been to shut the refineries down, only to make them better neighbors. Hilton came home from California, and he became like an ‘on’ valve for this campaign and this town. He just turned it loose.”

These days, Kelley patrols his old neighborhood in his 1995 Buick LeSabre, carrying the environmental activist’s low-tech equivalent of a James Bond gizmo — a “bucket-style” air monitor, literally a white five-gallon plastic bucket that pumps samples of air into sealable plastic bags. Kelley uses it to make “grabs” of polluted air during refinery upsets, then ships those samples to a private lab. “The refineries’ attitude has always been, ‘If you catch us, we’ll pay the fine — if you don’t catch us, so much the better,'” Kelley says. “So I decided to be the guy who started catching them.”

As we drive the streets of the Westside, Kelley — in shorts and flip-flops, his mobile-phone earpiece always in place — shows off the sights of what he calls “my toxic reality.” Our First stop is Carver Terrace, a cluster of red-brick buildings wedged between the fence lines of the Premcor and Motiva refineries. “I was born here,” Kelley says as we cruise the grid of streets. “And this is a federal housing project, meaning the people who live here pretty much by definition have nowhere else to go. They’re stuck living next to a refinery that throws toxic chemicals over its fence, sometimes every day.”

Kelley steers the car into the driveway of a white bungalow, and we head inside. The house is occupied by a woman and her three daughters, each of whom has been diagnosed with asthma. The girls’ inhalers sit on a table in the kitchen and the woman — who, like many people in the neighborhood, doesn’t want her name used — explains that in the past when one of the refineries had an accident, company representatives would troll Carver Terrace, paying $50 a head to residents who’d sign a waiver promising not to sue for damages. “They don’t do that anymore,” she adds.

A few miles away, Margaret Jefferson lives with her four children just outside the fence line of the BASF plant. “I grew up here, and I grew up with asthma,” she says matter-of-factly. “And when I had children, all four of them got asthma, too.” Jefferson says she used to have to take the kids to the hospital constantly; now she keeps inhalers and dozens of prescriptions within reach, and only ends up at the emergency room a couple of times each month. The doctors, she says, never tell her what might be the cause of the attacks. “They only treat it and send me home.”

There are hundreds of stories like Jefferson’s on the Westside; practically every household, it seems, is stocked with inhalers and a cupboard full of pills. Lillie Tilley, who lives half a block from the Motiva fence line, gets eyewash and Pepto-Bismol by the boxful at the local dollar store. (Eye irritation and nausea are among the symptoms of exposure to airborne toxins.) All three of Tilley’s children, aged 18 to 22, have asthma, as does she. “I did everything I could to make sure these kids were healthy,” she says, “but they still came up sickly. I was trying to get them to get their education and get out of here.” Asked whether she’s angry at the refineries, Tilley — who for years worked the graveyard shift at one of the plants — says she’s upset “because the children had to deal with it,” then adds, “For me, myself, I just accepted it. We count on these refineries to provide for our families, but they are killing us off.”

As we head away from the Westside, Kelley says it’s not just pollution his organization is trying to combat; part of the group’s goal is simply “to bring back a little hope to people here. I’m trying to get them to quit feeling so beat down, trying to remind them they’ve got to vote and protest things — otherwise, they’ll just get run over.” He talks about the Juneteenth Festival the group is co-sponsoring, with a musical and civic program on a plywood stage Kelley built himself, plus dunking booths, an inflatable Moonwalk, and horseback rides. And he talks about a lawsuit local residents are bringing in Texas state court — a massive “toxic tort” case against three refineries and three petrochemical plants. Five hundred people have signed on as plaintiffs in the case, Filed on June 25, claiming that plant emissions have damaged their health.

Spokespeople for the plants declined to comment on the specifics of the case. But several of them point out that there is no conclusive evidence linking refinery emissions to health problems among Port Arthur residents, and that a number of plants have installed cleaner equipment in the past 10 years. Industry representatives and civic leaders have formed a group to start an air-monitoring system and to donate money to community programs; industry officials have told the group that routine plant emissions have declined 50 percent since the mid-1990s and should drop another 25 percent over the next few years. “We are going to clean up the air,” says Rick Hagar, spokesman for Atofina Petrochemicals. “We all live near a plant here.” His own children, he notes, have been diagnosed with asthma; doctors initially suggested that plant emissions could be responsible, but then concluded that mold and mildew were the likely cause.

No one has ever conducted a comprehensive survey of what’s in Port Arthur’s air, or what it might be doing to people’s health. But a smattering of studies and government data suggests some troublesome patterns. In 1998, the Texas Department of Public Health found that the Westside had levels of ozone, hydrogen sulfide, and benzene (a known carcinogen) that constituted a “public health concern,” and that there was a “plausible relationship” between releases of those substances and health problems in the neighborhood.

Two years later, the EPA dispatched a Louisiana chemist named Wilma Subra to Port Arthur. Subra, who has won a MacArthur genius grant for her work on pollution in “fenceline” communities, asked Westside residents to fill out logs when they smelled a strange odor or experienced specific health problems. The symptoms people reported having — everything from headaches and sore throats to cough, nausea, diarrhea, and difficulty breathing — matched up exactly with the known effects of chemicals released by refinery “upsets,” according to Subra. Residents also reported air that smelled like “something dead,” “acid,” “chlorine,” “ammonia,” “oil-spill-like odor,” and “paint odor, very strong.”

In another study, in 2000, University of Texas toxicology professor Marvin Legator surveyed people living in public housing in Port Arthur and compared their health with a control group in Galveston, some 60 miles away. More than three-quarters of the Port Arthur residents had respiratory illnesses, compared with less than 10 percent in Galveston. More than half had immune-system problems, compared with just under 12 percent in the control group, and over 80 percent reported ear, nose, and throat irritation, compared with less than 25 percent in Galveston. “This is a pretty bad place,” says Legator. “Certainly it’s one that I wouldn’t want to live in.”

|

|

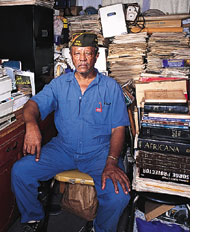

| Reverend Alfred Dominic started complaining about refinery pollution in high school in the 1930s; later, he launched a campaign to clean up Port Arthur’s air.

|

|

FUNDAMENTALLY, the argument over the Clean Air Act rules is a fight about dinosaurs — plants that are no longer supposed to exist. Back when Congress passed the current standards, in 1977, lawmakers faced a choice between forcing every industrial plant in the country to clean up immediately or spreading the change out over time. They opted for a process called New Source Review, under which companies had to install state-of-the-art pollution equipment when they expanded their plants — something that was expected to happen within a decade or two. “It would never have occurred to anybody,” says Curtis Moore, who was counsel to the Senate Environment Committee in the 1980s, “that some of those plants would still be in existence.”

As it happened, however, companies increasingly opted to evade the cleanup mandate by keeping their old plants going, rarely notifying the EPA even when they undertook major expansions. “Industry proved much more clever and creative at exploiting the loopholes” than Congress expected, says Donald Kettl, a political scientist who chaired a recent review of Clean Air Act rules by the National Academy of Public Administration.

Under pressure from both industry and environmentalists, the Clinton administration began to draw up changes to the Clean Air Act standards, especially to New Source Review. But the process took a much more aggressive turn under Bush, according to Bill Becker, who heads a national association of air-quality officials. The new administration was aiming not just to change the New Source Review requirements, he says, but to lift them entirely for many plants. “Someone in the administration got very greedy,” he says, “and put things in there that the industry had not even wanted.”

Why did the administration opt for such a sweeping revision? Part of the answer may lie with Vice President Dick Cheney’s energy task force, which for much of 2001 met in secret to draw up a plan for expanding the nation’s energy output. Representatives from power companies and refineries, the industries most affected by New Source Review, made contact with the task force dozens of times. A private memo to the task force from one of the nation’s largest electricity producers, Southern Company — which contributed a total of $2.4 million to Republican candidates and the GOP between 1999 and 2002 — warned that the EPA’s “extreme” use of New Source Review “threatens the safe, reliable, and efficient operation of energy production facilities across the country.” Industry leaders also hired former Republican National Committee chairman Haley Barbour and RNC chairman-to-be Marc Racicot to plead their case before the Cheney panel. In May 2001, the group issued a report recommending that the EPA review “the impact of [clean air rules] on investment” in utility and refinery expansion.

Nineteen months later, then-EPA administrator Christine Whitman released the New Source Review rules, characterizing the changes as a way to encourage plants to modernize and improve air quality. But according to some of the EPA’s own calculations, the effect could well be the opposite. Under the new rules, for example, plants can use their two worst-polluting years of the past decade as a baseline for future emissions — an approach that, critics note, effectively rewards the dirtiest plants. According to one EPA memo, that change alone would allow 50 percent of all the nation’s industrial plants to expand without being forced to clean up. The rules, notes Becker of the air-quality officials’ group, also create a major new loophole for plants that release toxic chemicals during “upsets” such as the one at Port Arthur’s Motiva. “If you are an attorney for industry and you can’t Find ways to escape New Source Review,” he says, “shame on you.”

The rule changes had an immediate, and drastic, effect on another Clinton-era EPA effort — a push to crack down on companies that had been operating in violation of the law for decades. In the late ’90s, then-EPA civil enforcement chief Eric Schaeffer launched enforcement actions against more than 150 companies for suspected New Source Review violations. Among the targets were dozens of refineries and petrochemical companies, including at least two in Port Arthur, as well as 51 of the nation’s dirtiest power plants — a collection of mostly Midwestern facilities that together are considered responsible for air pollution that kills as many as 9,000 people a year. The agency’s goal was to push the companies to negotiate settlements in which they would agree to reduce emissions and spend millions on community programs.

But the talks grew distinctly chillier, Schaeffer recalls, after January 2001. “When the Bush administration came in,” he says, “they basically said to these polluters, ‘Don’t worry, boys, we’re going to change the way we enforce requirements.’ And if you’re negotiating the law and, literally, they’re right behind you rolling the law up and putting it away, what kind of leverage did I have?” Schaeffer quit his post last year, complaining that the White House was “determined to undermine the rules we are trying to enforce.” The Bush administration has signed settlements in 17 of the cases he brought; negotiations in several others have stalled. The EPA has Filed no new complaints for New Source Review violations since Bush took office.

Before he left, Schaeffer managed to hammer out a cleanup agreement with Motiva, one of the Port Arthur plants his agency had targeted. The company promised to install new pollution-control equipment, start an aggressive self-auditing program, and pay Fines for future emissions violations. EPA officials say negotiations with other companies are continuing, but have not produced any settlements. One of the Port Arthur refineries, Premcor, announced plans for a massive expansion this spring.

Lillie Tilley, for one, has given up on waiting for Washington to force the Port Arthur plants to clean up. One of her sons works for a refinery — “It’s a livelihood,” she says — but when her daughter graduates from high school next year, Tilley hopes the girl will move to Seattle, where she has relatives. She remembers visiting the Northwest once and being struck by the tall trees and the mountains. Most of all, she remembers the air. “You could breathe,” she says. “You could take a deep breath and enjoy.”