When Bryan Hickson and Patricia Soto found out they were going to have a baby, the thrilled couple jumped into action. They watched YouTube videos about parenting, prepared healthy meals, and, since they planned to stay in their separate places to start, bought cribs and baby clothes for each of their homes. When Soto went in for ultrasounds, Hickson FaceTimed in from the warehouse where he works as a supervisor. When Soto went into labor, he held her hand through the contractions. Their son was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on a warm, cloudy day in late July of 2021. They named him Bryan Jr.

Two days after they left the hospital, Soto received a call from a social worker with Massachusetts’ Department of Children and Families, the state’s child protective services agency, informing her that DCF was taking custody of the child. Hickson and Soto assumed that DCF had made some sort of mistake. Soto did have a history with DCF: In 2018, the agency took custody of her older children due to allegations of domestic violence between Soto and her previous partner. But in the years since, her life had stabilized. Soto had steady housing and was working two jobs. Besides, a DCF social worker had visited Soto’s apartment during the pregnancy and confirmed she had appropriate furniture and baby supplies.

Yet, over the phone, the social worker told Soto that the agency was opening a case due to her DCF history, and warned that she could face kidnapping charges if she didn’t immediately bring the baby to the home of her sister, who would serve as an emergency foster placement. Soto protested: Why was this all coming up now? And why couldn’t the baby simply stay with his father? Hickson, who is 37, had no criminal or DCF history and was excited about parenting his first child. But DCF appears to have concluded that Hickson wasn’t in the picture; the agency referred to him as the “putative father” in court documents filed that day, alleging that Hickson’s whereabouts were unknown. Hours after the DCF call, the distraught couple dropped their infant off with Soto’s sister. (A DCF spokesperson declined to comment on the case, citing privacy rules.)

Hickson presumed that the matter could be cleared up quickly, that the infant would just be at his aunt’s for the night. But the next day, when Hickson appeared at the DCF offices with his son’s birth certificate in hand—the birth certificate he had signed at the hospital—he was informed that the matter would have to be settled in court.

When child protective services removes a child against the will of his parents, state laws typically require a hearing before a judge within a matter of days to ensure that the state made the right decision. The hearings function as a critical check on the power of CPS workers, whose job often entails making quick, life-altering judgment calls with limited information, and whose decisions can be tainted by racial and socioeconomic bias. (In Massachusetts, Black and Latinx children are 2.5 and 2.9 times more likely, respectively, to be involved with DCF as white children. Hickson, who is Black, told me he thought race may have played a role, but he was hesitant to jump to conclusions.) These court dates are called “72-hour hearings,” because the state law plainly says that DCF can have temporary custody of a child for up to 72 hours after an emergency removal.

The day after surrendering his child, Hickson appeared at the Springfield Juvenile Court to request a lawyer. A 72-hour hearing can only occur once all parties—parents and children—have attorneys. He was told he would have to call back the next day to see if a lawyer was available. When he called the next day, no lawyers were available. He repeated the routine the next day, and the day after that. “I kept calling every day. Every day, I kept saying, ‘Is there anything? Anything? Anything?’” Hickson recalls. “They’re like, ‘We have nobody. We have nobody. We have nobody.’” One week went by, then two. He took to Google, calling private lawyers one by one. At the same time, Hickson said, Soto spiraled into an all-consuming depression. (She and Hickson are no longer together but remain on good terms. She consented to sharing her story, though declined to speak at length to Mother Jones. Her name has been changed.)

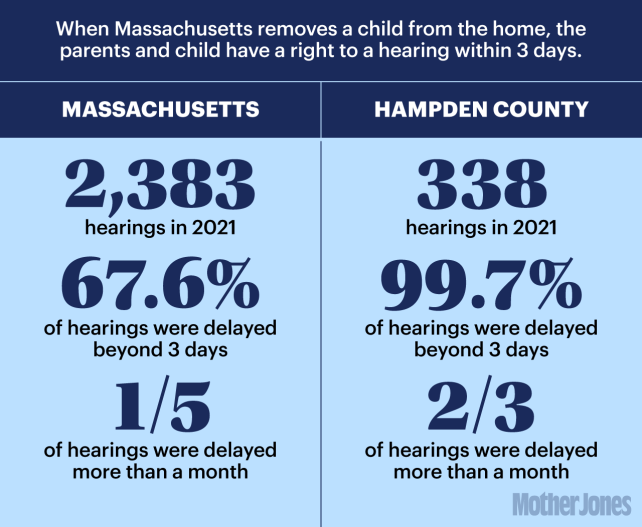

The couple had unwittingly stumbled into an open secret of the Massachusetts child welfare system: The state systemically fails to comply with its own legal statute, delaying 72-hour hearings well beyond 72 hours. Mother Jones found that the critical hearings are routinely pushed back weeks or months. According to state court records, of the 2,383 such hearings that took place last year, just one-third of them occurred within three business days. One-fifth of 72-hour hearings—more than 450 of them—didn’t occur for more than a month. In the meantime, children are typically placed in foster care while their parents wait to appear before a judge. The courts are meant to form a backstop to quickly rectify DCF overreach or mistakes, but the data suggests the backstop is failing.

The problem is particularly acute in Hampden County, Massachusetts’ poorest county and among its most diverse. Springfield, where Hickson lives, is the county seat and largest city in the western part of the state. According to state records, there were 338 cases with 72-hour hearings in the county last year. Of those cases, just one 72-hour hearing happened within three business days. Two-thirds of the hearings took place after more than a month. A spokesperson for the state Trial Court said that the vast majority of parents and children in such cases are indigent and have a right to a court-appointed lawyer, but there is a “persistent and well-documented shortage of attorneys.” The state is effectively stuck between two statutes: one that requires all parties to have legal representation, and one that requires prompt hearings. (Some hearings are delayed for other reasons, such as parents or children waiting on medical records or other pertinent documentation.) As of July of this year, more than 200 parents and children in Hampden County child welfare cases were, like Hickson, waiting for lawyers. As a result, their hearings were on hold.

The delays represent an “egregious violation of families’ rights,” says Dorothy Roberts, the University of Pennsylvania law professor who wrote about the failures of the child welfare system in her recent book, Torn Apart. Kally Walsh, a family attorney in Springfield, has seen the same scene play out for years: “I watch parents’ impassioned pleas: ‘It’s been a month, I haven’t seen my child. Please, please, can I have a lawyer?’ The guttural wail in the court. That kind of stuff never goes away. You always hear that in your being.”

In most cases, children who have been removed by DCF ultimately return to their parents, typically after parents have completed mandated services, like addiction treatment and parenting classes—a process that takes months or years. But in 10 to 20 percent of cases, judges decide at the 72-hour hearing that DCF has gone too far, and order the return of children to their parents immediately, according to estimates from the Committee for Public Counsel Services, the state’s organization of public defenders. Lengthy delays in those cases are particularly damning, say critics. It’s one thing to keep a family separated because a parent is, for example, in rehab; it’s another thing to keep a family separated because the state is short on lawyers.

As Hickson and Soto waited for their hearing, they were allowed an hour each week to visit their son. In the meantime, they received photos and videos: Bryan making a new face, Bryan being tickled. “You just see him keep growing faster and faster,” Hickson says. “And I’m like, ‘Damn, I’m missing all the good stuff.’ I’m missing the whole bonding situation. That’s a big part of their life, that first three, four months. That’s how they know who’s who. I almost felt like he might not know who I am.”

The problem goes back decades: A state-commissioned report in 2003 found a “critical shortage of attorneys available to handle the ever-increasing volume of child welfare cases in the juvenile courts,” and that the issue had reached “crisis proportions” in western Massachusetts. Yet, of all the courts that the authors visited, the Springfield Juvenile Court stood out. “One person we spoke with described the Springfield Juvenile Court system as a fiefdom, with each judge poorly managing his or her own docket,” it reads.

In late August, Hickson found a lawyer who was willing to take his case. At long last, the court scheduled the family’s 72-hour hearing for September 1—a month after Bryan Jr. had been removed. Hickson prepared to come online for the Zoom session at 8:30 in the morning, amassing every piece of paperwork he could think of that might be helpful to prove his fitness as a parent. But the hour came and went, with no 72-hour hearing.

It turns out that the court had pushed back the hearing, unbeknownst to Hickson or his lawyer. This is par for the course in Hampden County, says Jacquelyn O’Brien, a managing director of the Committee for Public Counsel Services: Instead of holding a 72-hour hearing, the court, overrun with cases, holds a meeting to schedule the hearing down the line. “The court is still routinely, all the time, scheduling ‘scheduling conferences’ within the 72-hour hearings, and then scheduling a 72-hour hearing from there,” she says. The court rescheduled Hickson’s hearing for September 21st, 49 days after Bryan Jr.’s initial removal.

Hickson reeled. What he had assumed was a simple clerical mistake had bloomed into something far more sinister. “It’s kidnapping, to me, just paid by the government,” he says. “If I were to do the same thing, I would go to jail.” Hickson knew that the longer a child is separated from his parent, the lower the chances of family reunification down the line. “When they started pushing out [the hearing], I’m like, ‘Here we go. They’re gonna make me jump through all these hurdles.’”

It’s tempting to try to blame the delays on a single person or institution: an apathetic judge, an incompetent DCF worker, an underfunded court system. The reality is, there is enough blame to go around. The delays stem from failures at virtually every level of the child welfare system. To begin with, there’s the high rate of DCF involvement, particularly in the homes of Black and brown families. “Certainly, from our perspective, the state was being very quick to pull kids from homes,” says Anthony Benedetti, chief counsel of the Committee for Public Counsel Services.

Then, there’s the chronic shortage of family lawyers, who do complicated, grueling work for relatively little pay, and without the societal recognition of their public defender counterparts in the criminal justice world. A persistent complaint from the court-appointed lawyers is that they feel the state hasn’t made family law sustainable. Until 2020, the lawyers made $55 an hour. This year, the state legislature increased the hourly rates to $85. The shortage of attorneys does seem somewhat solvable: In July, at the height of the backlog of child welfare cases in Hampden County, the state offered a onetime $1,500 bonus up front to lawyers who would take the cases. Within a matter of days, all 200 clients had lawyers. “It sends a message,” Benedetti says. “Despite all of the other legitimate concerns that attorneys give us about why they don’t want to take cases, at some point, it’s pure economics, right?”

But once all parties have lawyers, they encounter a shortage of judges. When we spoke, Debi Belkin, who leads a court-appointed child advocate program at the nonprofit Friends of Children, pulled up the docket for a juvenile court judge that day in western Massachusetts’ Hampshire County. “At 9:30, he had 16 cases that he had to do an overview on before 10:00 a.m. Then at 10:00, he has a full hearing, then two hearings at 11:00, at 12:00, another, at 12:30, arraignments. So, 20 cases this judge has to manage. Today.”

There is little data on just how common juvenile court delays are around the country, but legal experts say they are ubiquitous. Different locales have their own twists. In New York City, for example, the hearings typically begin within three days of a child’s removal, but they are divided into tiny segments, stretching out months, says David Shalleck-Klein, executive director of New York’s Family Justice Law Center. “The family court might take 5 or 10 minutes of testimony, and then adjourn the hearing out a few weeks, and then take another 10 or 20 minutes of testimony, and then adjourn it a few weeks, and then it turns out the attorney is going on vacation, or the judge is going on vacation, and it takes another month,” he says. “And all the while, a child is removed from their parents. This leads to a practice of hearings taking weeks or months to finish when they could be completed in less than a day.” A 2017 report from the Bronx Defenders found that the hearings, which are, by law, supposed to happen within three days of removal, typically lasted between one and six months, and took as many as two dozen court appearances.

Ultimately, the root causes of the delays transcend the shortage of lawyers or the number of cases to the broader culture of family law, long seen as a “stepchild field—a field that was unimportant,” says Martin Guggenheim, a law professor at New York University. In the corner of the legal world that deals with CPS cases, lawyers are scarce, appeals are rare, and, in the name of privacy, courts are closed to the public. As a result, they are impervious to public scrutiny. “There literally are countless courts in the country from which an appeal has never been brought,” Guggenheim says. “When you appear before a judge who has never been appealed, the judge understands that she’s all powerful. Whatever is done is done. There really isn’t a rule of law in this field.”

This is where Hickson’s experience in court diverges from the norm. When the hearing was pushed to late September, his attorney filed an appeal. It was then, it seems, that the court finally took notice of Hickson’s situation. Within days, an appeals court judge had responded, suggesting that Hickson’s lawyer file an emergency motion. On September 13, a Springfield Juvenile Court judge ordered that DCF give custody back to Hickson while he waited for his 72-hour hearing.

Bryan Jr.’s transfer from aunt to father was a jumble of feelings. Hickson was thrilled to have his son back. But Soto’s sister, who had bonded with her nephew over the previous six weeks, broke down in tears. “At this point, it’s like ripping the kid from her now,” remembers Hickson. At the 72-hour hearing a week later, a judge confirmed Hickson’s custody of his son.

Over the past year, Bryan Jr. has turned into a babbling toddler. Hickson brims with pride as he talks about his son, who, these days, seems to always want to take things apart and put things back together, and who has started mimicking his father as he brushes his teeth and combs his hair. The father and son live with Hickson’s parents, who take care of their grandson while Hickson works.

Recently, Bryan Jr. took his first steps. One moment he was holding onto the couch, and the next moment he had let go, taking two steps before teetering onto the floor. Hickson watched in awe. It is moments like these when he wonders what other milestones he missed during the first six weeks of his son’s life, and what milestones he may have missed if he hadn’t found a lawyer, or if that lawyer hadn’t filed an appeal, or if his record hadn’t been so squeaky clean.

It’s easy to imagine this alternate reality—he sees it in Soto, who is allowed just one hour of visiting time each week with her son.