When the sheriff’s deputies came for Gail Ritchey on May 21, 2019, she was outside her home in a suburb of Cleveland. Gail, who was 49 at the time, was just getting ready for a regular day: In a red fleece coat and a pair of blue jeans, her light brown hair in a bob, she was standing in front of her garage, preparing to drive down her cul de sac to go to her job at a dance studio.

When a sheriff’s deputy later told Mark Ritchey, Gail’s husband, that his wife had been taken in for questioning, he just remembers feeling surprise and shock. There must have been some mistake, he thought—it couldn’t be Gail they were looking for. Mark and Gail had been married for more than 25 years. They have three children together. Their oldest daughter has a daughter of her own. Gail volunteers in their local food pantry, and the family is very involved in their church in the close-knit community where they live.

Mark had no idea that his wife had been living with a secret.

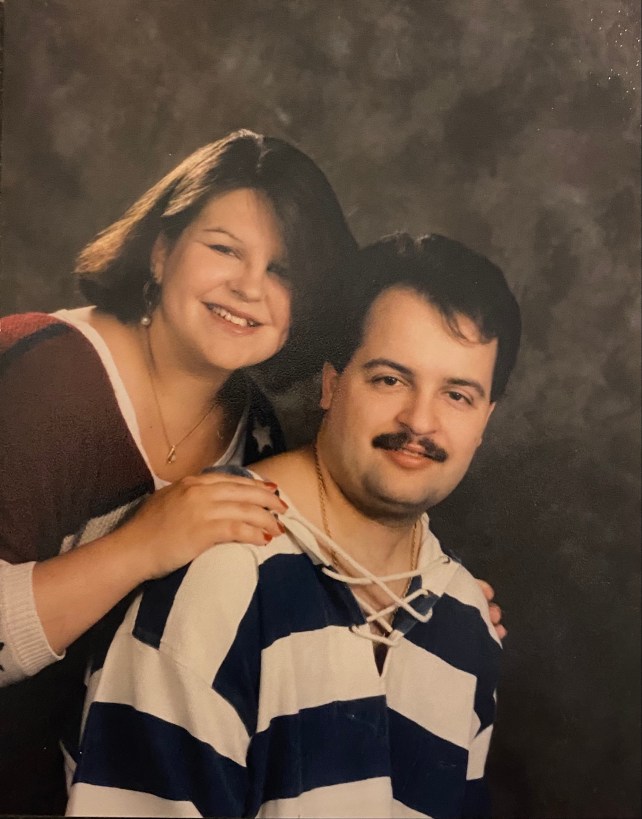

Just a few weeks before the arrest, a DNA sample of Gail’s confirmed what the sheriff’s department had suspected: In March 1993, a month before she turned 23, Gail had left a newborn baby in a trash bag in the woods by Sidley Road in Thompson Township, just over a half-hour drive from the home she and Mark now share. She had concealed the pregnancy from her parents, from her friends, from her church group, from the family she nannied for—and from Mark, whom she had been dating at the time and who was the father.

Animals had damaged the baby’s body and dragged it to the road, where two newspaper deliverywomen found it and called the police. The umbilical cord was intact, so it seemed that the birth had taken place without medical assistance. During the autopsy, the coroner determined that the baby had been born alive by floating a lung in water, a standard test at the time. Coroners also took microscopic tissue samples of the baby’s lung. The death was ruled a homicide, and the police began to look for a suspect. The Geauga County Sheriff’s Office put out an appeal to the mother of the child, promising to help guide her from further misdeeds if she came forward.

No one did.

Gail and Mark Ritchey’s 1994 engagement photo

Photo courtesy of Mark Ritchey

The community raised money for a funeral. Two members of the sheriff’s office carried the tiny white casket out of the church. The baby was buried at the Maple Grove Cemetery, where people left flowers and handmade garments and cared for the grave. They called the Baby Doe “Geauga’s Child.”

No interviews or physical evidence from the scene brought the sheriff’s office any closer to the mother of the baby. Investigators left a camera at the memorial site, hoping to catch the mother visiting; she didn’t. And in the years that followed, authorities looked into hundreds of leads, with no success. (The Geauga County Sheriff’s Office declined requests for comment, citing an active investigation.)

Then, in 2018, a detective tried something new: He submitted the baby’s DNA to an online genetic database, hoping to find a match. He found one: A man in Omaha, Nebraska, whose DNA had been submitted by his son-in-law. Knowing that someone in this lineage was the baby’s mother, authorities built out a family tree, asking family members for DNA samples along the way, until they narrowed it down to Gail. The man in the database was her third cousin.

Shortly after officers picked her up that day in May, Gail confessed to leaving the baby two decades earlier. She also admitted to abandoning another newborn two years before that, when she was 21, though she didn’t specify whether that baby had been born alive. When officers looked later, they could not find the remains, and she has not been charged with any crimes in connection with this second confession. But she was charged with murder in the first case. At a press conference, the sheriff’s office announced that it had finally found the mother of Geauga’s Child.

Gail pleaded not guilty, and her lawyers have argued the baby was not born alive. Her bond was set at $250,000, and, with that, the mother of Geauga’s Child was sent home in a tracking bracelet to wait and see if she would spend years in prison—if the life she had built over decades might matter more than one action of her youth.

The technique of submitting DNA to commercial databases to help solve crimes, and in particular to solve cold cases, is a controversial one, and it had only recently come to prominence when it was used to find Gail. In cases like these, scientists use DNA from crime scenes or unidentified remains to make genetic profiles, which are uploaded to a DNA database. The database finds profiles of people who share significant amounts of DNA and might be distant relatives of the person the sample came from. Once the database generates a list of matches, specialists known as genetic genealogists start in on the detective work—building family trees, tracking down relatives—until they find the person they’re looking for, whether it is the victim or the perpetrator. Earlier the same year that Gail was arrested, genetic genealogy was used to identify the Golden State Killer, a serial rapist and murderer who terrorized California in the 1970s and ’80s.

In the past four years or so, millions of Americans have entered their DNA into a handful of genetic databases. The most popular DNA-testing companies, such as 23andMe, do not allow law enforcement to access their data. But a few do under certain conditions, which has opened up a new way to solve the kinds of cases that previously would have been hardest to crack: those involving unidentified remains, or serial offenders who have eluded authorities for years. By now, hundreds of crimes have been solved using genetic genealogy, catching relatives who may never have considered the broader privacy implications and what their DNA was being used for.

A small but growing subset of these cases are neonaticides. Debbie Kennett, a genetic genealogist based in the United Kingdom, has been tracking these investigations; she’s identified 32 neonaticide cases just in the United States in which genetic genealogy has been used to search for the mother, though she suspects that there have been more.

Kennett also collects news clippings about the cases. The stories, perhaps unsurprisingly, typically fail to address any of the systemic failings that experts explain often exist in these cases—particularly, Kennett told me, “the issues of female reproductive rights, or the problems with the health care and social services systems which failed to identify these at-risk women to prevent the tragedies from happening.”

News coverage of Gail’s case was similar. After she was arrested, the local news channel featured breaking news video of her in the waiting area. In a mugshot released to the public, she wears a blank, stunned expression. Coverage emphasized that the technology that led authorities to her had been used to find the Golden State Killer, and that the crime was one of the most important outstanding cases in the county—how during all of those years, Gail never visited the gravesite, and how, after her arrest, she did not appear contrite. Reporters noted how she called the baby an “it.”

But, her husband Mark told me, “I saw that picture that was released in the media. Just look at the face. Does that look like a face that’s not remorseful? Her cheeks are red, her eyes are bloodshot.

“This woman is torn up.”

Neonaticide, and child murder more generally, is an unimaginably horrible crime. It prompts a visceral reaction; just hearing about it can make your stomach turn. There are few crimes where the perpetrator and the innocent victim, a newborn, are quite so clear. But neonaticides are in fact quite complicated, and a closer read may ask us, as Kennett does, to consider that there can be more than one victim in these crimes—both the baby and the mother. For many mothers, the crime is rooted in her difficult circumstances; many of these women face cultural, social, psychological, and religious factors that make them feel as if it would be impossible to be pregnant, let alone raise a child. So they conceal and sometimes even go into denial about the pregnancy, according to Susan Hatters-Friedman, a forensic and reproductive psychiatrist. The pregnancy causes many of these women extreme psychological stress. The mother may deliver and then abandon or kill the baby in secret—hoping desperately that no one else knows.

So when the knock comes at their door 20 or 30 years later, they have to grapple with what a very much younger version of themselves had done and what it means now for them and their family. This kind of confrontation with the past can have unintended consequences. In 2019, law enforcement approached a woman in Pueblo, Colorado, about a newborn who had been abandoned in the Arkansas River in 1996. A few days later, she died of suicide. Authorities tested her DNA and confirmed that the baby was her child.

The US criminal justice system is not equipped to deal with these nuances and complications. Unlike several other countries, the United States has no special legal provisions for women who commit infanticide. But perhaps more importantly, the system does little to grapple with the critical questions that are provoked by these cases, questions I encountered repeatedly in my reporting: Should law enforcement be pursuing them, knowing the person they are looking for is almost always the mother? Is this a legal matter—or a psychological one? Are these cases a legitimate and ethical use of genetic genealogy, let alone police resources? And finally, what is the goal of sending someone like Gail, who went on to have a family and contribute to her community, to prison? Research shows that most of these women go on to lead productive, law-abiding lives.

Forensic psychiatrist Phillip Resnick, a leading expert on neonaticides, doesn’t dispute that these mothers should be found, but he disagrees with the ways in which we respond. “The need to seriously punish them is an open question, because you’re certainly not protecting society,” he told me. “It’s only the issue of vengeance.”

These questions are only becoming more urgent as the country makes a mad dash to further winnow reproductive rights and to police what people do with their own bodies. “It’s part and parcel of a larger strategy essentially to control and limit the choices of women,” said Erin Murphy, a New York University law professor and expert on forensic DNA testing. “The kind of profiles here are of women and girls in a crisis moment in various ways. They might be in a crisis moment because of the way the pregnancy came about, because of their own mental health issues, because of a lack of support in their family, because of a lack of a social safety net.”

Still, after they are arrested, women like Gail enter a system designed to enact punishment. They are examined by the press, their community, and sometimes a jury, all people who hold ideas about what makes a good mother, what makes a penitent mother, and what crimes are completely unforgivable. Lost in this righteous scrutiny is the basic question of who also might deserve some compassion.

The term neonaticide was coined in 1970 by Resnick to describe a specific act of infanticide: the killing of a newborn within 24 hours of birth. (In some cases, the baby is stillborn or dies after birth without the mother intending it; these are not considered neonaticides.) His research showed these are the most dangerous hours, that the first day of life is statistically when a person is at the highest risk of homicide. These crimes are almost always perpetrated by the child’s mother and tend to follow a pattern different from other child murders. Women who commit neonaticide tend to be younger mothers—in their teens or early 20s. Many conceal their pregnancy from those around them in response to a situation that seems untenable. A small subset of these women deny the pregnancy even to themselves, and a smaller subset have a serious psychological illness that makes them believe the pregnancy is not happening. According to one paper, 91 percent of neonaticides involve concealment or denial.

Before they commit the act, these mothers do not tend to exhibit signs of major psychological disorders. And because the timing is so soon after birth, a neonaticide happens before the onset of any postpartum psychosis. But before the birth, these women may be unusually passive and indecisive; they may be immature and suffer from poor self-esteem. Some psychologists explain they also exhibit borderline personality traits—such as instability, impulsivity, and trouble with relationships—as well as fears of being abandoned. After the fact, women who have commited neonaticide can experience PTSD or depression. In a small number of cases, women are found to have committed multiple neonaticides.

Gail with one of her children

Photo courtesy of Mark Ritchey

Neonaticides happen all over the world, and for different reasons—in some countries, because a specific gender is preferable, or there are pressures on resources. Japan, for one, has two different words for neonaticides: mabiki, or family culling, and anomie, the killing of an unwanted newborn by a single mother. In the West, women who commit neonaticides are often unpartnered, with limited means, and living with their parents. The strongest commonalities are in their relationships to the people around them: They may have a poor relationship with their parents or may be worried about being abandoned by them should a pregnancy be discovered. They may be overwhelmed and have difficulty coping. Perhaps the religion the family practices leads to concealment. In general, they do not seek medical care, and those not in denial spend months concerned about ramifications of the pregnancy. The overarching shared experience is that the pregnancies are unwanted.

Another possible factor is limited access to abortion services. In the decade after Roe v. Wade was decided, one report counted fewer neonaticides in the United States than before. Another 1995 study found that regions in the United States with more limited access to abortion had higher rates of neonaticides. (At the same time, another study from 1995 found there was no correlation.)

But because of their invisibility, neonaticides are hard to reliably track. Conservative estimates indicate hundreds of neonaticides happen in the US each year. Research also suggests that the United States may have higher rates of neonaticide than other developed countries; one study that focused on North Carolina showed the incidence was 2.1 per hundred thousand newborns per year, while another study showed a rate between .07 and .18 in Finland.

While some neonaticides are discovered almost immediately, others, as we’re seeing now with cases like Gail’s, are found out years after the fact—which allows authorities to see whether the mother went on to commit other crimes. According to Resnick, most do not, and a majority of women who commit neonaticide go on to raise other children. Gail, for one, had another child five years later, and two more after that.

Over the past several decades, there has been some recognition of the problem of abandoned or killed babies and attempts to address the issue. In countries such as France, hospitals allow mothers to come in anonymously, give birth, and leave the baby to be adopted, a measure that depathologizes unwanted pregnancies and has seen some success. In the United States in the late 1990s, states started passing safe-haven laws, sometimes known as “Baby Moses Laws,” which allowed parents to leave newborns at designated sites such as police stations, fire stations, and hospitals. There is no organized reporting on safe-haven laws, so it is hard to tell how effective they are. In some states, such as New Jersey, these measures may have made a difference in the number of abandoned infants; in others, there’s been no measurable change.

But none of these steps address the underlying systemic problems that often create the conditions that can lead to neonaticide. This leaves in place dangerous social attitudes, as well as a lack of access to sex education, to birth control, and to a health care professional who can help, particularly without parental intervention.

When the law finally catches up with these women, the US legal system isn’t required to consider any extenuating circumstances, including their mental health. The United States has no infanticide laws that would find women who killed their own children less culpable than other murderers. But such laws exist in other countries: Introduced in England in 1922, and now on the books in more than 20 countries, including Ireland and Canada, these laws are based on the idea that a woman’s mind is altered by childbirth and lactation, that the hormonal changes are akin to a psychological condition. These countries create separate standards for women who commit these crimes; the maximum charge is manslaughter, and many women are given probation instead of a jail sentence.

But in the United States, if a coroner determines that the baby was born alive, the mother can face a murder charge. This means she can be charged at any time in the future, as murder doesn’t have a statute of limitations. Once charged, she is left to the discretion of the prosecutor and judge. Sentences vary, ranging from probation to life in prison, depending on the charges. The only state that has any mitigating provisions is Illinois, which asks for judges to take into account during sentencing postpartum depression or psychosis. In the US, the average sentence for neonaticide is 9 years.

The main reason there are no specific legal provisions for neonaticides is because if a woman was not in her right mind, she can arguably use the insanity defense. But because of the seemingly cold-blooded nature of the crime, few women charged with neonaticide have employed one successfully; the concealment that so often accompanies the crime suggests to juries the crime was premeditated and committed by someone who was sane. “Suggesting that they didn’t know what they were doing was wrong at the time,” said Resnick, “is very unlikely to succeed.”

The US approach to neonaticides horrified Kennett, the UK-based genetic genealogist. She told me that in light of how the US criminal justice system operates, and of how many of these cases were being solved with genetic genealogy, she was shocked to see “the way that the women were treated as murderers rather than treated kindly and compassionately because of the extenuating circumstances and the societal attitudes of the time.”

The psychiatrists I spoke with also view the American response as overly punitive. Resnick has seen many of the convicted women receive harsh sentences, including life in prison. “Neonaticide, with its particular conditions, is especially a crime where the women, especially as they get older, are not repeat offenders,” he told me. According to Resnick, a majority of women who commit neonaticide and are brought to justice go on to become good mothers. This “suggests that neonaticide is a situational crime rather than a crime of bad character,” he said.

Richard Martinez, a forensic psychiatrist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, similarly argued that the criminal justice system hasn’t handled these cases fairly.

In 2020, he testified in the case of Jennifer Katalinich. In 1996, when she was just 18 and a student at Colorado State University, she gave birth in her dorm room. In denial, and without her roommate knowing, she smothered the baby and then wrapped it up, scaling down into a reservoir before leaving it. She didn’t even look to see the gender; she only learned it was a girl from news reports later. She was arrested 23 years later.

At the sentencing hearing, Martinez testified that Katalinich had completely dissociated from the pregnancy and said she had believed several pregnancy tests that had come back negative. “She went on to have an exemplary life, and she had two more children and a marriage. It’s hard to imagine how justice would be served in this case by placing a person in her predicament in prison,” Martinez told me. She pleaded guilty and ended up with a 90-day jail sentence, three years in a community-service program, and probation. “I realized everyone involved in this case is a victim,” her husband said at the sentencing hearing. (Katalinich declined requests to speak with me.)

At times, psychiatrists and psychologists who study this phenomenon meet with law enforcement to try to reduce sentences. Resnick sat down with the prosecutor and law enforcement in Gail’s case and talked about the psychology of neonaticide in the hopes of reaching a plea agreement. Gail, he pointed out, was gainfully employed and a mother. “She is happily married, and to take her out of her life and put her in prison…I questioned the value of that,” he told me.

Her defense team rejected the plea. She’s been charged with two counts: aggravated murder and murder. If convicted of both charges at the trial that starts late this month, Gail would face a sentence of life imprisonment, and be eligible for parole after 20 years.

Gail, who has been awaiting trial at home, declined to speak with me directly. But she agreed to stand next to Mark a few times when we spoke. Mark told me she would poke him if she wanted him to adjust what he was saying, or to convey something, or if he was sharing too much. But she didn’t need to.

When we connected over Zoom, Mark spoke carefully. He was in his home office. There were pictures of the kids in the background behind his desk. Mark, who has short gray hair and crinkly eyes, typically wore a worried expression. In some ways, especially because of the years-long wait leading up to the trial, he seems to be regularly reliving the day the sheriff’s deputy showed up and turned his life around—as well as everything that led up to it. He remembers Gail as a young woman, trying to live a good life in the eyes of God and her family. She had been a Rainbow Girl—doing community service and charity work with the Baptist church in Lyndhurst, Ohio, that she regularly attended with her family.

Gail with one of her children; Gail with Mark

Photos courtesy of Mark Ritchey

But her home life wasn’t easy. According to Gail’s lawyer, Steven Bradley, she was verbally abused by her father. Bradley sent me a photograph of Gail and her sister when her sister was graduating from high school, one he said he was going to show at trial. In the photo, her sister is gleaming and accomplished, wearing lipstick and a cap and gown, while Gail looks uncomfortable in her own skin. When she became pregnant, according to Bradley, she didn’t know where to turn. She felt she couldn’t tell her parents, or Mark, or her church group. Mark also introduced me to several of Gail’s friends on a Zoom call one night last June; one recalls how they bonded over trouble at home and fathers who drank. The people who knew her then described her as kind, anxious, eager to please and take care of people.

Gail and Mark were already in a serious relationship when she got pregnant, though not yet engaged. Mark said it upsets him to think that she had to bear the secret alone. “I don’t know if I could ever forgive myself,” Mark told me. “That’s my child, and she didn’t call me. Why didn’t she tell me what was going on in her mind?”

Mark seems most struck by what Gail’s decision making must have been like in her early 20s. Their children are around that age now, and to him, they still seem like kids. A pregnancy in those circumstances didn’t fit Gail’s plan for her life, even though she eventually wanted a big family, one of Gail’s friends told me. The friends agreed that it would have been impossible for Gail to tell anyone about the pregnancy. One of the women had an abortion when she was 24, and she kept it a secret for most of her adult life. She said she believed that sharing the news would have disappointed everyone, and she imagined Gail felt the same.

For Mark, his wife keeping her pregnancy a secret was a kind self-sacrifice, “because she felt there were too many other people that were going to get hurt, period,” he told me. “Whether it was me, whether it was from mom or dad or family or others around her that knew her, that’s where it all came from.”

One friend told me everyone should have a Gail in their life. Gail spent time nannying for another friend, who told me that had she known everything she knows now, she still would have employed her.

In some ways, the United States is moving forward in addressing postpartum issues, with better screening for postpartum depression and psychosis and with more openness in conversations around miscarriage and infant loss. But so far neonaticide has been excluded—leaving a tangled web of debates about what motivates investigators, as well as the proper use of the law and technology in these investigations.

With neonaticides, law enforcement officials can be motivated by pressure to solve an outstanding homicide in their county, as well as personal belief and their own individual pain. It’s clear that they carry their own trauma. This may provide insight into the way in which the criminal justice system has prosecuted neonaticides. Gail’s case, for one, seems to have been personal for many officers, some of whom had even carried the infant’s casket.

In another example, Andy Josey was an investigator with the sheriff’s department in Fort Collins, Colorado, during the Jennifer Katalinich case. He told me it still sticks with him. On August 24, 1996, he responded to a call about what appeared to be a newborn girl. The remains were discovered in a plastic bag floating on top of the water at a place called Horsetooth Reservoir. A few young boys had been swimming and thought they happened to find a doll.

Josey attended the autopsy, where he said they determined the baby was born alive. At the time, his wife was a deputy treasurer for the county, and they decided to take the baby in as their own. They named her Faith, and gave her a gravestone in a nearby cemetery and a memorial service. Over the years, they would visit and bring gifts. “I’ve worked child homicides in addition to this,” Josey said. “And we would always be able to identify who the culprit was. This was a whole different ball game.”

In 2019, when the sheriff’s department made a DNA match to the baby found in the reservoir, Josey was retired. Still, he attended the trial. He said he was moved by what her family went through, but he was disappointed by the end result and the minimal jail time for Katalinich. “The sentence was…on the lenient side,” he told me. “Thankfully she was charged with criminally negligent homicide because there’s no getting around the fact that it was a homicide and it would have been really inappropriate to eliminate that as a charge.”

He said that the most important thing for him as an investigator was being able to use her confession to piece together what had taken place. I asked if perhaps he would have been happy to just know what happened but have Katalinich walk free—to have the matter resolved outside the criminal justice system. It was an idea that was hard to conceive of, particularly given his background. “Investigators always want convictions,” he said, “because that’s what we’re working for.”

In other words, conviction is often seen as the only way to achieve closure for law enforcement, and in the criminal justice system more broadly. As it stands now, there is no option where these women don’t serve time, or where all parties involved can seek mental health support. Gail has never been offered or received counseling or psychological help for what she went through. Most members of law enforcement who deal with these crimes don’t either. These cases, explained Murphy, the NYU law professor, are “a reason to support counseling or support traumatic intervention or PTSD interventions for first responders and law enforcement, not a reason to incarcerate someone 40 years after the fact.”

Murphy has doubts about whether these cases should be pursued at all, given the diversion of resources from other crimes and especially because of the strong emotions involved. “It’s inappropriate because the police [should be] acting for the people,” she told me. “The more they’re acting in their personal interests, the more problematic the decision making.”

Prosecuting neonaticides can also raise a slew of thorny legal and ethical questions about using genetic genealogy to solve crimes, and more specifically to identify women decades after the fact. There are no legal guardrails to shape how this technology is used, or what cases get worked on (nor any rules against pulling DNA samples of suspects without their consent). The US has no provision against using DNA databases to solve neonaticides (or any other crimes), but in some countries, it’s less prevalent. As the United Kingdom’s Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group—a public body sponsored by the Home Office—considered its approach to the use of genetic genealogy, it recommended against using the technology in decades-old cold cases involving newborn remains: “Identification of cases where genetic genealogy may be appropriate must be carefully defined to enable an ethical and reasoned decision to be made (avoiding the prosecution of women who abandoned their babies decades ago, based on analysis of the deceased baby’s DNA…).”

Brianne Kirkpatrick, a genetic counselor and the founder of Watershed DNA, an organization that assists people in making sense of DNA test results, warned that even as some DNA databases now ask users to opt-in if they want to allow law enforcement to use their DNA, they probably aren’t considering the moral complexities of a Baby Doe case. (Other DNA databases don’t allow law enforcement use at all.) She is also bothered by the resource issue, arguing there are other more pressing cases to solve with genetic genealogy—to put the time, effort, and money toward unsolved rapes, or current cases involving an assailant who might act again.

The most prominent genetic genealogist in the US is arguably CeCe Moore, the chief genetic genealogist at Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA-technology company in Virginia. It has helped law enforcement solve 15 Baby Doe cases using genetic genealogy, according to Paula Armentrout, a vice president and co-founder. (To put this in context, a recent press release says they have solved over 200 cases involving investigative genetic genealogy.) Parabon doesn’t actively decide what cases to take; law enforcement chooses which cases to send to the company. Moore doesn’t see her role as being judge and jury. “Our work is identification, and everything else is up to the courts,” Moore told me. “This is not vengeance on our part.”

Although Gail was arrested in 2019, her trial has been postponed multiple times. Meanwhile, time has moved forward. Old secrets and unknowns have been replaced with new uncertainties. Multiple milestones have passed: a new granddaughter was born in May 2021; Mark and Gail recently adopted a dog named Cinnamon. And Gail has stayed close with her friends, taking care of them when their relatives are sick and dying. She still does her volunteer work. Her activities now just come along with the tracking bracelet.

Nevertheless, it’s been hard for her inner circle. Even the friends who spoke to me over Zoom, who were incredibly supportive of Gail, were scared to be quoted by name, fearing repercussions. Mark told me that people outside their immediate community and on social media have been less than supportive. The family stopped attending the church they had been going to, but they missed their Sunday morning ritual. Mark and Gail have recently been attending a new church, which her daughter’s boyfriend attended. Before they came, they were nervous about how they were going to be received. Gail was initially quiet and kept to herself—but one woman, a friend who ended up on my Zoom, greeted her with a hug and the congregation followed with open arms. Not everyone knows about what happened.

The trial is finally supposed to start late this month, though her lawyers are still trying to move the case out of Geauga County, where they contend that no jury could be impartial. They are crafting arguments about Gail’s mental health and her other circumstances at the time of the birth. They are also planning to argue that the baby wasn’t born alive. Crucially, they got evidence of the lung-float test barred from trial, since it’s been widely criticized as unscientific. But the medical examiner is still planning to show slides of the lung tissue during trial.

Finally, they told me they want to show the “full picture of Gail.”

The Ritchey family

Photo courtesy of Mark Ritchey

Mark will be at the trial alongside his wife. He admits he hasn’t allowed himself to feel anything. He thinks Gail hasn’t really absorbed the loss of the child either, and may not be able to, until this chapter in their lives has ended. He cannot wait for his family to have this behind them. He is worried about Gail being able to withstand the ordeal of the trial, and is thankful for the new church, which has provided Gail with a lot of solace.

“I think she hasn’t fully grieved yet,” he told me. “She’s been a mother to three wonderful kids. She has kept these feelings internal for so long, it may take as long as it took to expose it.”

For Mark and the Ritchey family, the divisions between good and bad and right and wrong used to seem more obvious. But living through the legal, emotional, and psychological intricacies of Gail’s case has shifted their world view. Now things don’t always seem as black and white anymore.

“These cases, they often remind us of our struggle between how we understand punishment, culpability, and mercy,” Martinez, the forensic psychiatrist, told me. “Much of what goes on in the criminal justice system involves a perpetrator and the victim, and in many of these tragedies, yes, there’s a perpetrator and a victim, but the nuance and the complexity of the story really requires a more compassionate understanding on our part.”

Mark has been researching neonaticides and thinking about ways to help women like Gail. Some of her friends have done the same, reading the work of Hatters-Friedman and others. They are shocked and saddened by what they have learned women go through. Mark is thinking about starting an organization to support women who find themselves in similar circumstances, horrified by the stress it causes and the vagaries in sentencing. “Nobody should be judged for their worst choice or mistake,” Mark told me.

One evening, on the Zoom call with Mark and Gail’s friends, they concluded with Mark saying a prayer—for something good to come of all of this, for someone to be helped.